How can we make better progress in developing media literacy in Europe? And what should the European Commission itself be doing?

I’ve attended a couple of European media literacy conferences over the past few months; and I’m now looking ahead to the launch of the International Association of Media Education taking place in Italy at the beginning of July. I’ve heard about some very interesting projects, but I’ve also been worrying about where media literacy policy is going in Europe – and in particular, how the European Commission might be able to support it more effectively.

Through the 2000s, media literacy began to rise up the European policy agenda. There was a Communication on the topic in 2006, followed by a formal Recommendation published by the Commission in 2009. But since that time, there has been very little progress on actually implementing these policies.

That’s not to say the Commission has been sitting on its hands. In 2013, it published a report on ‘testing and refining criteria to assess media literacy levels in Europe’. It has commissioned several ‘state of the art’ surveys, including a survey of film literacy published in 2013, and an extensive ‘Mapping of Media Literacy Practices and Actions’, published early last year. It is also currently funding various pilot projects involving multi-country teams, as part of educational and research programmes like Erasmus Plus and Horizon 2020. Further funding has come from programmes designed to support the audio-visual sector, such as MEDIA and Creative Europe.

That’s not to say the Commission has been sitting on its hands. In 2013, it published a report on ‘testing and refining criteria to assess media literacy levels in Europe’. It has commissioned several ‘state of the art’ surveys, including a survey of film literacy published in 2013, and an extensive ‘Mapping of Media Literacy Practices and Actions’, published early last year. It is also currently funding various pilot projects involving multi-country teams, as part of educational and research programmes like Erasmus Plus and Horizon 2020. Further funding has come from programmes designed to support the audio-visual sector, such as MEDIA and Creative Europe.

A victory of sorts was achieved last year, when media literacy was included in the Audiovisual Services Directive, the key document that defines the EU’s future media and communications policy. In its introduction, the document provides a fairly generic definition of media literacy, and makes the right noises about how it is a ‘fundamental skill’ and ‘an important factor for active citizenship in today’s information society’. Yet media literacy is not mentioned anywhere else in the document: all its detailed recommendations and plans for action relate to the development and regulation of the media industries, and issues such as copyright and consumer protection.

A couple of months ago in Barcelona, I attended the final conference of one of these EC-funded projects, Transmedia Literacy. The team have produced some really interesting research, especially focusing on young people’s informal learning; they have created a very systematic and comprehensive taxonomy of media literacy competencies; and, to their credit, they have also translated many of these insights into practical classroom activities via a ‘teacher’s kit’. The book based on the project is available on open access here.

A couple of months ago in Barcelona, I attended the final conference of one of these EC-funded projects, Transmedia Literacy. The team have produced some really interesting research, especially focusing on young people’s informal learning; they have created a very systematic and comprehensive taxonomy of media literacy competencies; and, to their credit, they have also translated many of these insights into practical classroom activities via a ‘teacher’s kit’. The book based on the project is available on open access here.

This week, I was in Ghent at the final meeting of another project, EMELS, which has been developing a European Media Literacy Standard for Youth Workers – addressing a sector that, at least in the UK, is often poorly supported. Like the Transmedia researchers, the team has been working on a framework of media literacy skills; and they have supplemented and supported this by developing some really useful materials that can be used in both informal and more formal classroom settings. You can find all this on their website.

There are a great many positive dimensions to such projects. They obviously promote cross-European dialogue. If such funding does little else, one might say that it has created a cadre (perhaps an elite) of professionals who feel and behave in ‘European’ ways, rather than purely national ones. These projects also help to build capacity among researchers and practitioners, which is especially important in countries where there is less alternative funding available. And of course they generate outcomes – reports, frameworks, learning materials – that can potentially be used in many different contexts.

However, there are also some difficult questions that need to be addressed here. In many instances, the partners on such projects are small NGOs with very limited funding of their own. Such organizations are bound to find themselves ‘chasing the money’ – and that often means pursuing the latest moral panic. In recent years, policy-makers have frequently looked to media literacy as a quick-fix solution to a never-ending succession of media-related issues: hate speech, fake news, cyberbullying, social media addiction… the list goes on. Such issues are typically considered in isolated, fragmented ways, rather than as part of a much more comprehensive and coherent media education strategy.

In this context, media literacy often serves as palatable alternative to centralized regulation. Governments are reluctant to restrict the operations of the commercial market, yet they have to come up with solutions to the problems that markets inevitably throw up. And so, as is so often the case with just about any social problem one cares to name, they pass the buck to education.

Meanwhile, European funding brings other bureaucratic imperatives. The Commission is hungry for its ‘deliverables’, yet it rarely seems to consider how these deliverables might be used or implemented over the longer term. Just as project teams start to think about dissemination, the money runs out, and their deliverables end up in a digital graveyard. Some of the reports I have mentioned are so detailed (the 2016 Mapping Study, for example, runs to a whopping 452 pages) as to render them unreadable. Meanwhile, many of the countless elaborate websites that have been ‘delivered’ have just disappeared, since the budget will not allow the hosting to be paid once the project has been completed. Because the project partners do not own the copyright on what they produce, it is hard for them to publish or repurpose it for other contexts.

It’s now almost fifteen years since the European-level discussion of media literacy began, and yet it seems as though most of the participants are still limbering up, and haven’t even made it to the starting block. We have seen a great many feasibility studies and maps of the field, and several (more or less useful) pilot projects, but very little has been sustained over the longer term. There has also been a great deal of overlap here. One of the media educators I met in Ghent told me that his organization had tracked down twenty-seven different media literacy frameworks before then starting work on its own!

Part of the problem here is a structural one. In the UK, there is a sorry history, which I’ve recounted in detail elsewhere. In 2003, the new media regulator, Ofcom, was given responsibility for ‘promoting media literacy’; but by 2010, the government had effectively abandoned this in favour of a much narrower focus on internet safety and ‘digital inclusion’. The key problem, in my view, was that media literacy was defined as an issue for media policy (in effect, for the regulator) rather than a matter for educational policy.

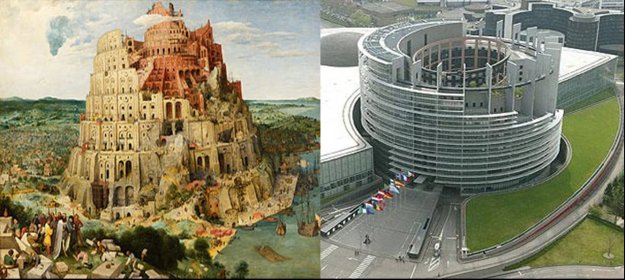

This is a problem that can also be seen at a European level. Media literacy seems to fall awkwardly between several policy domains (and hence several European Directorates-General, or DGs). Meanwhile, formal education remains a responsibility for member states, which means that the EC can only provide generalized advice in this area. It also seems that the ‘home’ of media literacy has been relocated from one DG to another, with responsibility being spread across and between them.

This has led to some shifts in focus as well. While the discussion in the 2000s was about media, in recent years there has been a bifurcation between film and digital media – in which other media (such as television or the press) seem to be disappearing from view. Thus, on the one hand, we have projects about ‘film literacy’, which partly derive from the imperative to preserve national film industries and the European ‘film heritage’ in the face of global competition. And on the other, we inevitably have an enormous amount of attention paid to digital media – but largely defined as technology rather than as media. In this context, media literacy is often at risk of being reduced to a narrow set of functional or instrumental skills in handling equipment or using software. A more comprehensive and critical form of media literacy is missing.

Among the most recent documents in this area have been several reports on ‘digital competencies’. The Commission has published several elaborate reports generated by ‘expert groups’, for example on Digital Competence for Citizens and Consumers, and most recently for Educators. These reports offer detailed frameworks, complete with targets and levels, and some delightful infographics – like this one of ‘learning to swim in the digital ocean’. In this context, media literacy begins to morph into digital literacy (one wonders what analogue literacy might entail…), or into ‘information and data literacy’ – although here again there are enormous overlaps between these frameworks and the many others that have been generated over the years. It’s hard to tell who these documents are intended for, what status they have, and how they could ever be put into practice.

Among the most recent documents in this area have been several reports on ‘digital competencies’. The Commission has published several elaborate reports generated by ‘expert groups’, for example on Digital Competence for Citizens and Consumers, and most recently for Educators. These reports offer detailed frameworks, complete with targets and levels, and some delightful infographics – like this one of ‘learning to swim in the digital ocean’. In this context, media literacy begins to morph into digital literacy (one wonders what analogue literacy might entail…), or into ‘information and data literacy’ – although here again there are enormous overlaps between these frameworks and the many others that have been generated over the years. It’s hard to tell who these documents are intended for, what status they have, and how they could ever be put into practice.

However good such documents may be, there’s a need to think about how fine words (or reports or frameworks or beautiful websites) might translate into actions. Experience in the UK, and in countries like Canada and Australia, which have a long history of media education, suggests that several aspects need to be in place if we are going to see genuine progress. To be sure, we do need policy documents and frameworks; and international documents of this kind, coming from authoritative sources like the EC or UNESCO, can lend weight to arguments we might be making at a national level. We also need resources, and again there are some useful ones coming out of the European projects I have mentioned. However, we also need professional development for teachers; we need support for teacher networks; and we need research and evaluation (ideally conducted by or with teachers themselves) that explores how these prescriptions work out in practice. If media education is going to happen, it cannot be a top-down affair: teachers need to have ownership of it. All of this implies a long-term strategy, rather than a succession of pilot projects and one-off ‘deliverables’.

I’ve been quite critical of the EC here, but my argument should not in any way be seen as an argument for Brexit. It’s actually been quite depressing to look at the outcomes of the projects I have mentioned, because they mostly seem so constructive and so well-informed. There are certainly questions about where and how this work might be implemented. But in the post-Brexit world, those of us in the UK will no longer be able to participate in these projects and dialogues, or have a stake in creating these kinds of resources. What’s happening to us is disastrous and stupid, and nobody seems to be able to stop it…