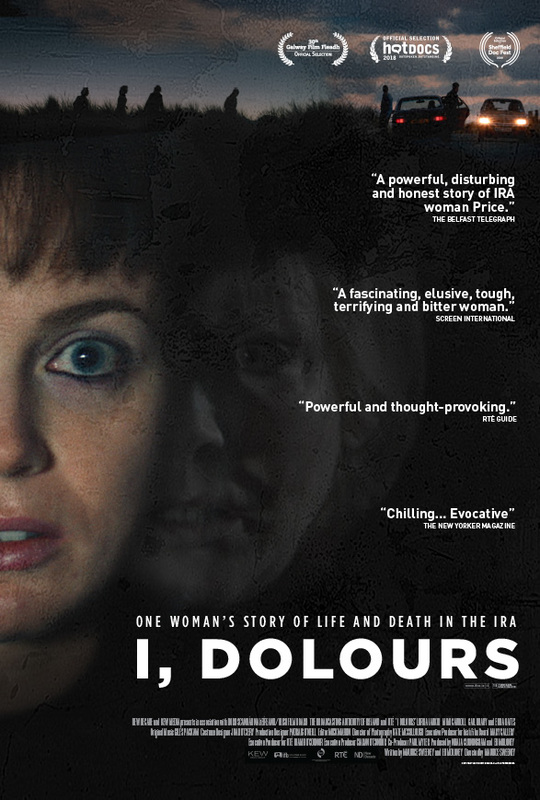

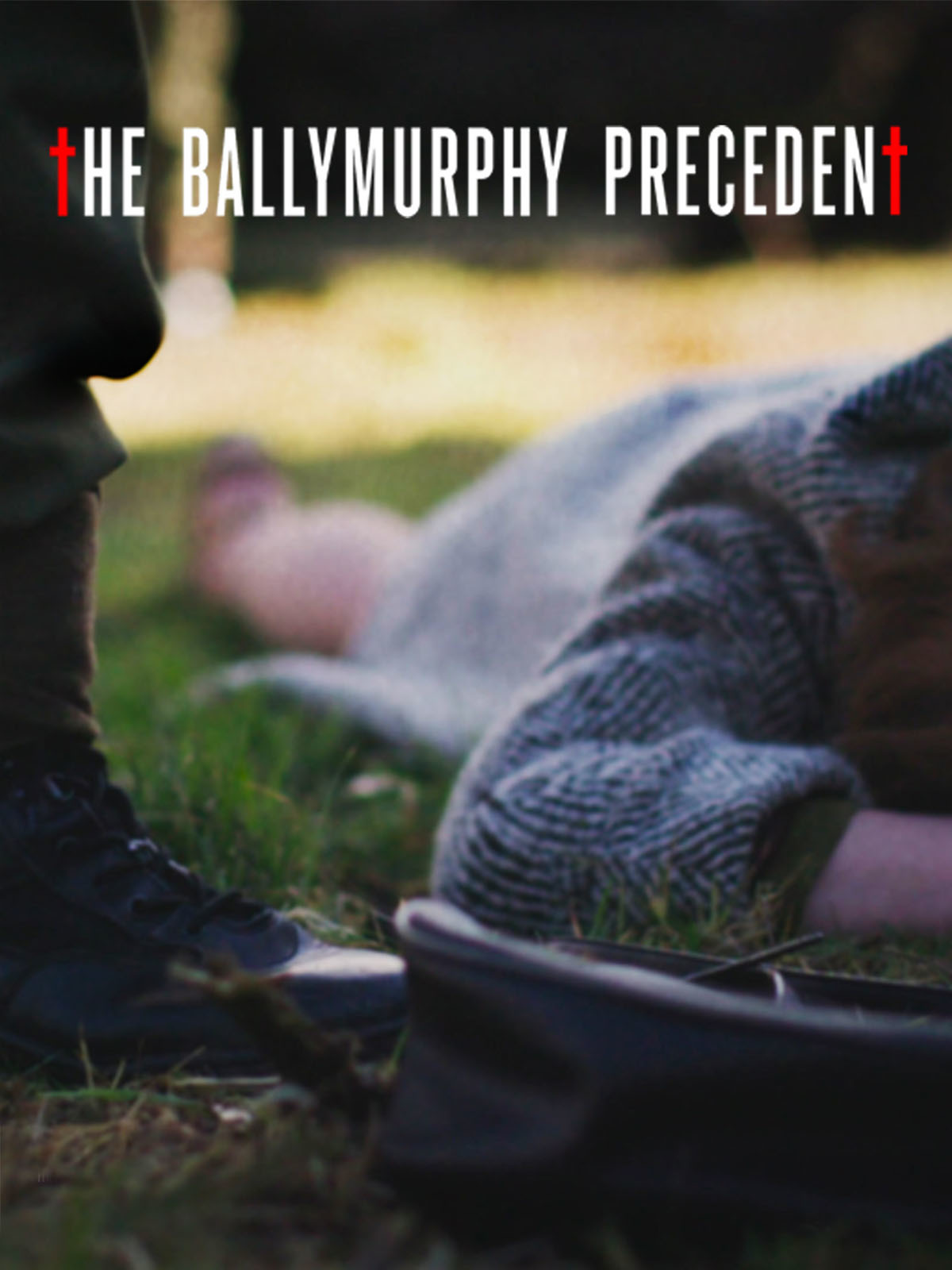

Three documentaries about the conflict in Northern Ireland raise some interesting questions about how we represent history: I, Dolours (dir. Maurice Sweeney, 2018); The Miami Showband Massacre (Stuart Sender, 2019); and The Ballymurphy Precedent (Callum Macrae, 2018).

Three documentaries about the conflict in Northern Ireland raise some interesting questions about how we represent history: I, Dolours (dir. Maurice Sweeney, 2018); The Miami Showband Massacre (Stuart Sender, 2019); and The Ballymurphy Precedent (Callum Macrae, 2018).

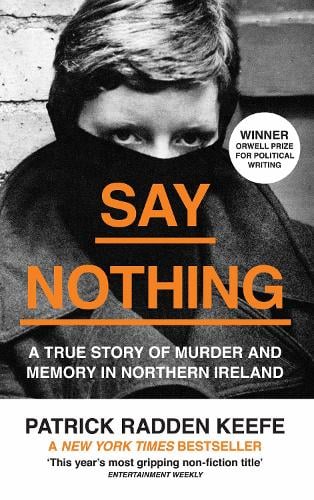

This piece was initially prompted by my reading of Patrick Radden Keefe’s prize-winning book about the conflict in Northern Ireland, Say Nothing (2018). The book is one of many publications in recent years that seek to interpret the history of the conflict by recovering first-hand evidence of events that in many instances took place half a century ago. Documentary film is also playing a significant role in this respect, and the difficulty and complexity of this process is apparent in the three films I will be considering here.

While various official investigations have come and gone, the truth about the conflict in Northern Ireland remains intensely disputed. Documents have been lost or destroyed; archival material may be partial and misleading; and facts have often been deliberately hidden from view. Individual memories may be less than reliable; and for many reasons, people may still be unwilling to admit to their role in these events, or indeed actively seek to mislead.

There are additional challenges in fashioning such material into narratives that are both coherent and engaging, and that purport to tell the truth – especially for the benefit of audiences who may be more or less informed about what took place. Selection and manipulation are unavoidable. A certain element of drama, and even of sensationalism, may be necessary, especially in creating a product that can be sold. And yet truth is not necessarily the first casualty of this process, especially in a situation where there are many potential truths to be told.

Say Nothing traces the stories of four key individuals: Jean McConville, a mother of ten, whose abduction and murder by the IRA was one of the most notorious unsolved crimes of the conflict; Brendan Hughes, a former IRA commander, who later led the first hunger strike by interned republican prisoners; Dolours Price, the first woman to join the IRA, who took the bombing campaign to London; and Gerry Adams, who denied his own past in the IRA and became one of the architects of the Good Friday peace agreement.

Say Nothing traces the stories of four key individuals: Jean McConville, a mother of ten, whose abduction and murder by the IRA was one of the most notorious unsolved crimes of the conflict; Brendan Hughes, a former IRA commander, who later led the first hunger strike by interned republican prisoners; Dolours Price, the first woman to join the IRA, who took the bombing campaign to London; and Gerry Adams, who denied his own past in the IRA and became one of the architects of the Good Friday peace agreement.

The book is a genuine page-turner; yet although it is reasonably impartial, it only tells one part of the story. Paramilitaries operated on both sides of the conflict – and indeed loyalist paramilitaries significantly outnumbered the Provisional IRA, and killed more people. And of course, there was also the British army, whose incursion into the province in 1969 significantly escalated the conflict. Meanwhile, the events now known as ‘The Troubles’ need to be understood as part of a much longer history of British colonialism in Ireland (on which, the third episode of David Olusoga’s recent historical documentary series Union provides a succinct and authoritative account): make no mistake, the so-called ‘Troubles’ were ultimately a war, part of a long and still unresolved war for independence.

The issue with which Say Nothing begins and ends – and possibly what inspired Radden Keefe, a staff writer for the New Yorker, to write it – is to do with a collection of files stored in the archives at Boston College in the United States. Over the early 2000s, researchers based at the college had been conducting oral history interviews with several key participants in the conflict, on condition that they would only be released after their death. However, the interviews came to the attention of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, who attempted to seize them, and were then the subject of various government subpoenas on both sides of the Atlantic.

One of these interviews was with Dolours Price, a charismatic image of whom adorns the cover of Radden Keefe’s book. It later emerged that Price had given other interviews – one of which (with Ed Moloney, one of the directors of the Boston College project) forms the backbone of the film I, Dolours, which was not released until some years after her death in 2013. I was sufficiently intrigued to seek out that film, and this led me on to several others covering events during the same period, a couple of which I’ll be discussing here.

The key questions in Say Nothing, and (in various ways) in the films I will be writing about, are to do with truth and memory. Radden Keefe is assiduous in his efforts to find the truth about the murder of Jean McConville (along with others known or suspected to be informers who were ‘disappeared’ during the course of the conflict); and he also fully refutes Gerry Adams’ denial that he was ever a member of the Provisional IRA. And yet there are other untold stories that continue to haunt the memories of those who survived those times…

I, Dolours

I, Dolours (released in 2018) was directed by Maurice Sweeney. It was written and co-produced by Moloney, with funding from RTE (Irish public television) and the Irish Film Board. It is currently available on Amazon Prime.

As its title suggests, the film traces the story of Dolours Price, mostly in the form of her personal testimony: it is to some extent a confession. However, it also offers a wider narrative of events in Northern Ireland at the time; and it does this in relatively conventional ways, using archive film with captions, as well as interview footage with Price from 2011, which at times provides a kind of voice-over narration.

Less conventional, however, and more problematic for some critics, are the elements of reconstruction (which are not labelled as such). An actor (Lauren Beale) plays the role of Price through her childhood, in scenes that focus particularly on her relationship with her Aunt Bridie, who had been maimed and blinded while handling explosives for the IRA in the late 1930s. Lorna Larkin plays Dolours as an adult, tracing her involvement in the Civil Rights movement, then joining the Provisional IRA, and later becoming involved in bombing campaigns, including in London. We then see her arrest and imprisonment, the hunger strikes and force-feeding endured by herself and her sister Marian (played by Gail Brady) and their anorexia and eventual release – as well as (very briefly) her marriage in the 1980s and 1990s to the noted actor Stephen Rea.

The narrative is largely chronological, although there are shifts between various moments in the past and present (or at least the 2011 of the interview). The film opens in 1999 as Price learns of the discovery of the bodies of some of those who were ‘disappeared’ by the IRA, and occasionally flashes back to her childhood. The reconstruction scenes are mostly (though not always) in colour, as distinct from the (mostly) black and white of the archive footage. However, this isn’t consistent: some of the reconstruction is in black and white, and is cut into the archive footage, perhaps deceptively so. For example, the scenes of loyalist attacks on Civil Rights protesters at Burntollet Bridge in January 1969 – the event that motivated Price to join the ‘Provos’ – includes reconstructed shots showing the sisters’ involvement.

There are also some striking moments where the film breaks the ‘fourth wall’, and the actor playing Price addresses the camera directly. In one scene, for example, she outlines the structure of the Provisional IRA; while in another, she embraces her mother as the latter visits her in prison, but then speaks words written by Price in her diary at the time, about the need to avoid showing weakness to the enemy. On the other hand, the 2011 interview is shot in a conventional ‘talking head’ style, with Price looking off camera towards the interviewer.

There are also some striking moments where the film breaks the ‘fourth wall’, and the actor playing Price addresses the camera directly. In one scene, for example, she outlines the structure of the Provisional IRA; while in another, she embraces her mother as the latter visits her in prison, but then speaks words written by Price in her diary at the time, about the need to avoid showing weakness to the enemy. On the other hand, the 2011 interview is shot in a conventional ‘talking head’ style, with Price looking off camera towards the interviewer.

At one moment in particular, the story of the killing of Jean McConville, whom the IRA suspected of being an informer, we become aware that Price is offering a version of the truth. She prefaces her response to the interviewer’s question by saying that she has to be careful about what she says. The film (or more specifically, the film’s reconstruction of the circumstances of McConville’s death) effectively shows that Price was responsible, along with two others; although Price’s interview/narration talks about ‘the volunteers’ in the third person. On the other hand, while she subsequently agrees that ‘disappearing’ people should be considered a war crime, she also says that she believed informers shouldn’t have been killed in secret, but should have had their bodies displayed in public as a warning to others.

Indeed, in her interview, Price’s position appears ambivalent, even inconsistent. She expresses great anger with Gerry Adams, effectively describing him (as have others in republican movement) as a traitor or a sell-out. As she points out, the aims of that movement (British withdrawal from Ireland) were not achieved in the Good Friday agreement. The IRA, she argues, effectively ‘lost the war’. ‘I couldn’t live with the failure of my life’s purpose…’ she says. ‘It had all been for nothing’. Price claims she no longer approves of violence, and has dissociated herself from the republican movement, but she is also fiercely critical of Sinn Fein, Adams’s political party – and, perhaps most powerfully, she also directly and unequivocally names Adams as an IRA commander. Adams opted for peace and political power – which required not just compromise, but also a flat denial of his own past. But it is hard to see what else he might have done.

In much of this, the viewer is left to reach their own conclusions. Of course, we see many of the events through the eyes of Dolours; and there are moments where the film seems to direct us strongly towards sympathy for her. Particularly in the reconstructions, she and her sister come across as charismatic and even glamorous. The dramatized sequences of her being force-fed are particularly harrowing, and at one point, they are intercut with archive footage of Margaret Thatcher at her moment of victory in 1979, entering Downing Street and quoting St Francis of Assisi (‘where there is discord, may we bring harmony’, and so forth). On the other hand, the film doesn’t flinch from showing some of the chilling consequences of her actions. At times, the tone seems melancholic, for example in the reconstructions of her childhood, or her eerie night-time journeys across the border to deliver McConville and other informers to their deaths – scenes reinforced by mournful music. The tone is generally meditative rather than didactic, let alone propagandist.

In much of this, the viewer is left to reach their own conclusions. Of course, we see many of the events through the eyes of Dolours; and there are moments where the film seems to direct us strongly towards sympathy for her. Particularly in the reconstructions, she and her sister come across as charismatic and even glamorous. The dramatized sequences of her being force-fed are particularly harrowing, and at one point, they are intercut with archive footage of Margaret Thatcher at her moment of victory in 1979, entering Downing Street and quoting St Francis of Assisi (‘where there is discord, may we bring harmony’, and so forth). On the other hand, the film doesn’t flinch from showing some of the chilling consequences of her actions. At times, the tone seems melancholic, for example in the reconstructions of her childhood, or her eerie night-time journeys across the border to deliver McConville and other informers to their deaths – scenes reinforced by mournful music. The tone is generally meditative rather than didactic, let alone propagandist.

Despite the testimonial or confessional stance of the film, therefore, the issue of truth remains a troubling one. The boundaries between past and present, truth and falsehood, and documentary and fiction, are blurred. This makes for ambivalent viewing, although perhaps that is appropriate given the history it depicts.

ReMastered: The Miami Showband Massacre

Released in 2019, The Miami Showband Massacre is a more routine production, but it begins to tell another side of the story. Directed by Stuart Sender, it is one of a continuing series of music-related documentaries in the Netflix series ReMastered.

Like several others in the series, the film focuses on a mystery – one that is perhaps even more difficult to decipher than the case of Jean McConville. The Miami Showband was an extremely popular pop/cabaret band of the time, even referred to by some as the ‘Irish Beatles’. The band was made up of four members from the Irish Republic, and two (both Protestants) from the North. They travelled frequently across the border, playing to mixed (Catholic and Protestant) audiences. On one such trip, returning from a gig in the North in July 1975, the band’s vehicle was stopped at an army check point. There was an explosion, in which two loyalist paramilitaries were killed, probably inadvertently; and then three of the band members were shot dead. The key question is whether the killings were committed with the collusion of, and even at the behest of, the British army.

The film follows the investigation into the murders by the two surviving members of the attack, who were effectively left for dead at the scene. We hear from the bandleader Des McAlea, but the main focus is on Steve Travers, the bass player. Travers is seen at work on his computer, looking through documents, and testifying at the hearings of the Historical Enquiries Team (run by the Northern Ireland Police), and other public events. He is in the course of putting together a court case against the British Ministry of Defence. (Two years after the film appeared, he settled for substantial damages, not least because the government was threatening to bar all prosecutions relating to the war in Ireland – although there was no admission of liability.)

Along the way, we are presented with a rather different story about the conflict, which focuses on the counter-insurgency and counter-intelligence activities of the British army. This covers the role of Frank Kitson, an expert brought in by the British because of his experience in suppressing resistance movements in Kenya and Malaya; the collusion between the British army and loyalist paramilitaries, such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA); and the punishment of British whistle-blowers like Colin Wallace and Fred Holroyd. While concerns about such collusion were raised by Irish politicians at the time, the British government consistently denied this. Government non-co-operation meant that charges were dropped, and notorious murderers went unpunished.

Along the way, we are presented with a rather different story about the conflict, which focuses on the counter-insurgency and counter-intelligence activities of the British army. This covers the role of Frank Kitson, an expert brought in by the British because of his experience in suppressing resistance movements in Kenya and Malaya; the collusion between the British army and loyalist paramilitaries, such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA); and the punishment of British whistle-blowers like Colin Wallace and Fred Holroyd. While concerns about such collusion were raised by Irish politicians at the time, the British government consistently denied this. Government non-co-operation meant that charges were dropped, and notorious murderers went unpunished.

(Although Radden Keefe’s book describes some of this, it is not addressed in any detail. By contrast, Brendan McCourt’s film Collusion (2015) shows how the British government used groups like the UDA and the UVF as a kind of ‘fifth column’, lending weapons, intelligence and expertise in order that they could assassinate Catholics – not just IRA members, but innocent civilians in their homes, in the Republic as well as in the North. There were no clear rules on how these paramilitaries were handled, allowing space for rogue actors; but the government essentially turned a blind eye to their activities, and continues to prevent any investigation or legal process.)

The UVF claimed responsibility for the Miami Showband killings at the time; and the film establishes, fairly definitively, that they were operating with the involvement of the British army, and quite possibly at the instigation of the British – although Travers himself is wary of this charge. The film names Robin Jackson of the UVF (also known as the Jackal) and Robert Nairac, a notorious British Army officer who (it implies) was actually present at the attack. In case of Jackson, there was fingerprint evidence linking him to the murders, although this was contested and he was acquitted in court.

Perhaps the abiding mystery here, however, is why the musicians were killed. There was no evidence that they were involved in the armed struggle in any way. The film implies that the attack might have been part of a wider attempt to seal the border in order to prevent the passage of the IRA (who were certainly smuggling weapons across) – but it is hard to see how this would have required them to be murdered. At one point, Travers obtains a letter from the UVF to the government unearthed from official archives, in which the UVF complain that they have been supplied with faulty detonators ‘as in the case of the Miami Showband’. It certainly appears that the bombs exploded prematurely, which may imply that the assassination was a tragic mistake. Nevertheless, bombs were planted in the band’s van when they were stopped. Contemporary conspiracy theorists might suggest that this was some kind of false flag operation, although that would seem equally unlikely.

To some extent, this is a film about memory. It keeps returning to publicity shots of the band, smiling and posing in their flares and wide-lapelled jackets; and there is also a short film clip of a youthful Travers that is used several times. In the present, Travers is shown walking alone in the fields around his house, still seemingly coming to terms with the trauma he has suffered and his memories of his fellow band-mates – or perhaps also enduring a kind of survivor’s guilt. Like I Dolours, this is also a film about trauma, about the long-term effects of such events – which in Price’s case are as much physical as psychological. In this case, trauma is tied up with a continuing struggle to establish truth, although there is a sense that truth will never be confirmed – and that even if it could be, it would not heal the wounds.

To some extent, this is a film about memory. It keeps returning to publicity shots of the band, smiling and posing in their flares and wide-lapelled jackets; and there is also a short film clip of a youthful Travers that is used several times. In the present, Travers is shown walking alone in the fields around his house, still seemingly coming to terms with the trauma he has suffered and his memories of his fellow band-mates – or perhaps also enduring a kind of survivor’s guilt. Like I Dolours, this is also a film about trauma, about the long-term effects of such events – which in Price’s case are as much physical as psychological. In this case, trauma is tied up with a continuing struggle to establish truth, although there is a sense that truth will never be confirmed – and that even if it could be, it would not heal the wounds.

Thus, we see Travers participating in the work of the Police Historical Enquiries Team (which was wound up in 2014), and there is also reference to the British government’s Consultative Group on the Past (which reported in 2009). (The HET was found by the British government itself to have conducted its work in a very partial manner, especially glossing over instances of collusion with loyalist paramilitaries.) Even so, Northern Ireland has had no real equivalent to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. One reason why people like Dolours Price were unwilling to go on the record was the sense that they would be prosecuted for crimes, or indeed war crimes (as I’ve noted, Price admits that assassinations of informers were war crimes). In one scene, Travers is shown sitting down with a former member of the UVF, but they fail to find common ground on the truth. Once again, the search is unresolved. At the very end of the film, Travers concludes ‘The sound of the music will far, far outlast the sound of their guns and their bombs’ – although one might well question his apparent optimism.

The Ballymurphy Precedent

The final film I’ll consider in detail here is The Ballymurphy Precedent (2018), directed and narrated by Callum Macrae. The film was funded by Welsh Film Cymru in association with Channel 4. At least at the time of writing (2023), it seems to have sunk with little trace (there are very few reviews), but it is one of the strongest and most moving of these films. It is currently available on Amazon Prime.

Like the other films I have considered above, The Ballymurphy Precedent provides a brief ‘back story’ of the conflict, although in this case it traces a somewhat longer history, going back to the partition of Ireland in 1921. It tracks the Civil Rights movement of the late 1960s, the arrival of the British army, and key events like the ’Battle of Bogside’ of 1969, which spurred the IRA back into action. (I suspect more detailed comparisons would establish some important differences in how these films choose to tell the back story, especially given that this is a history viewers cannot be assumed to know or remember.)

The film’s key focus is on an attack by loyalist paramilitaries and the British army on the Catholic housing estate of Springfield Park in Ballymurphy, Belfast. The attack took place on 9th, 10th and 11th August 1971, just as internment began (internment was a policy of imprisonment without trial, which was almost exclusively applied to Catholics, including Civil Rights activists, and rarely to loyalists). As many as 600 soldiers from the first paratroop division, including snipers, were deployed. Despite claiming they were involved in a ‘gun battle’ with the IRA, no evidence ever came to light showing that the troops came under fire. The army shot 40 people, several of whom were executed at close quarters. Ten unarmed civilians were killed, including a priest (waving a white flag), a church worker (who was also an army veteran), a woman and a child. A youth worker bringing bread and milk for children was shot at and died of a heart attack. These people were mostly running for their lives, and were shot indiscriminately – and in some instances repeatedly. The army removed several bodies to its barracks, where those not already dead were beaten; others were left to bleed to death over several hours.

Para One was the division that was sent into Derry a few months later in January 1972 to suppress a Civil Rights march, which resulted in the massacre known as Bloody Sunday. This was another key event that escalated the conflict, and effectively drove many to join the IRA. This accounts for the film’s title: the Ballymurphy massacre was a precedent for Bloody Sunday, and the film suggests that if there had been a proper investigation of Ballymurphy, Bloody Sunday might never have happened, and the wider conflict might have turned out very differently.

Para One was the division that was sent into Derry a few months later in January 1972 to suppress a Civil Rights march, which resulted in the massacre known as Bloody Sunday. This was another key event that escalated the conflict, and effectively drove many to join the IRA. This accounts for the film’s title: the Ballymurphy massacre was a precedent for Bloody Sunday, and the film suggests that if there had been a proper investigation of Ballymurphy, Bloody Sunday might never have happened, and the wider conflict might have turned out very differently.

According to its opening caption, the film is based on ‘witness statements, survivors’ recollections, official depositions and autopsy reports’. It uses many of the familiar conventions of archive documentary, with expert talking heads, including the historian Dr. Geoff Bell, and a ‘voice of God’ voice-over narration. However, there is no sham impartiality here: the film’s viewpoint is very clear. For example, its discussion of civil rights makes some striking parallels with the situation in the US, comparing the Selma, Alabama march of 1965 with the equally defining moment of the march at Burntollet in 1969, and equating the Southern whites and the loyalists. It argues that while the army was allegedly brought in to ‘protect Catholics’, it immediately took sides against them, endeavouring to ‘restore the law and order [of] the sectarian state’. The film contains shocking archive footage of the British army suppressing riots, looting Catholic homes, and attacking women and girls. The ‘voice of God’ narration (by the film’s director, Callum Macrae) very clearly conveys disgust and anger at what took place.

While it does include interviews with two British soldiers who were stationed in the province at the time, the film’s account of the events at Ballymurphy is conveyed largely through the testimony of the survivors, and through reconstructions (although interestingly, these are labelled as such, which is not the case in the other films I’ve considered). These scenes are frequently accompanied by dramatic or melancholy music, as appropriate; and there is also considerable use of drone and slow-motion footage. The film undoubtedly uses a range of ‘fictional’ techniques to evoke emotional responses, and makes little pretence at neutrality.

While several of the murders are filmed through the sights of the snipers’ rifles, much of the reconstruction is shown through the eyes of the children. In some instances, the survivors talk more-or-less direct to camera; in others, they are shown walking round the area pointing out where key events unfolded. Much of this testimony is highly emotional, and it becomes clear that these emotions are still so raw partly because of the cover-up and the campaign of PR misinformation that followed the massacre. The police investigation was minimal, and it appeared that most people in Northern Ireland accepted the army’s version of events. (It’s notable that the press officer responsible for this campaign, Mike Jackson, later became head of operations in NI and eventually of the whole British Army.) While many survivors were immediately evacuated (some to the South), the remaining population of the estate was stigmatised to such an extent that they were unable to talk about what had happened.

While several of the murders are filmed through the sights of the snipers’ rifles, much of the reconstruction is shown through the eyes of the children. In some instances, the survivors talk more-or-less direct to camera; in others, they are shown walking round the area pointing out where key events unfolded. Much of this testimony is highly emotional, and it becomes clear that these emotions are still so raw partly because of the cover-up and the campaign of PR misinformation that followed the massacre. The police investigation was minimal, and it appeared that most people in Northern Ireland accepted the army’s version of events. (It’s notable that the press officer responsible for this campaign, Mike Jackson, later became head of operations in NI and eventually of the whole British Army.) While many survivors were immediately evacuated (some to the South), the remaining population of the estate was stigmatised to such an extent that they were unable to talk about what had happened.

Like The Miami Showband Massacre, then, this is a film about memory. Several of the survivors say that the making of the film has given them their first opportunity to talk in public about the events. In the final part of the film, the survivors are shown coming together to form a support/investigation group: we see them examining inquest reports, soldiers’ statements, and maps of the area. The official inquest into Ballymurphy was in fact reopened in 2011, although the investigation was consistently resisted by the British Ministry of Defence; by that time, the report on Bloody Sunday had already let Para One off the hook. After the film was made, the Ballymurphy report was finally published after many delays in 2021: it found the victims were innocent, and required the MoD to pay damages to bereaved, but there was no public apology.

Conclusion

The three films I’ve discussed are among a growing number that have appeared in the last ten years or so looking back to the history of the war in Northern Ireland: others include The Disappeared (dir. Alison Millar, 2013), Bobby Sands: 66 Days (Brendan Byrne, 2016), Collusion (Brendan McCourt, 2015, mentioned above) and Act of Union (Neil Clerkin, 2021). There have also been two major BBC series, Spotlight on the Troubles: A Secret History (2019) and Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland (2023). Other such films have relied wholly on reconstruction, with greater or lesser elements of invention: these include Steve McQueen’s debut film Hunger (2008), starring Michael Fassbender, which is about the hunger striker Bobby Sands; and more recent ones like The Troubles: A Dublin Story (Luke Hanlon, 2022), which also claims to be ‘based on’ real events. (There is a useful list on IMDB here: ; and some material from an extensive archive project here.)

These films are gradually uncovering a hidden history of double agents, informers, leaks, denials and cover-ups. Amid claims and counter-claims, skeletons are still being found in cupboards more than fifty years on. Some critics and online commentators have accused such films of ‘rewriting history’, and even of peddling conspiracy theories; although judgments seem to depend very strongly upon the writers’ political position (this is very apparent in online comments on I, Dolours, for example). It would be interesting to know how such films are understood, not just by those who can remember some of the original events, but also by younger generations, for whom ‘The Troubles’ might well appear to be rather a tiresome and even irrelevant legacy.

In many instances, this is not so much a matter of rewriting history, but of writing it for the first time – although of course, history is always being written and rewritten. In place of truth and reconciliation, films like these serve as a kind of archive, albeit a partial and unreliable one. The unsatisfactory resolutions of most of the cases they represent suggest that the struggle for truth is bound to continue. Documentary film is a key part of this process; but here, as in considering documentary more broadly, the pursuit of truth means that we need to acknowledge the complex aesthetics, ethics and epistemology of documentary making.

As I write, in mid-December 2023, it is impossible not to think of the situation in Gaza. There are undoubtedly historical parallels here, although there are also significant differences. So far, in little more than two months, more than 20,000 civilians have been killed, predominantly by Israeli forces. By contrast, in the Troubles in Northern Ireland, 3,700 people — both combatants and civilians — were killed over nearly thirty years. And alongside a conflict that seems doomed to escalate, we are seeing a similar campaign of misinformation, manipulation of evidence, and sheer denial of reality. History is being actively constructed, even as it happens.