Revisiting a classic avant-garde documentary from Soviet Russia.

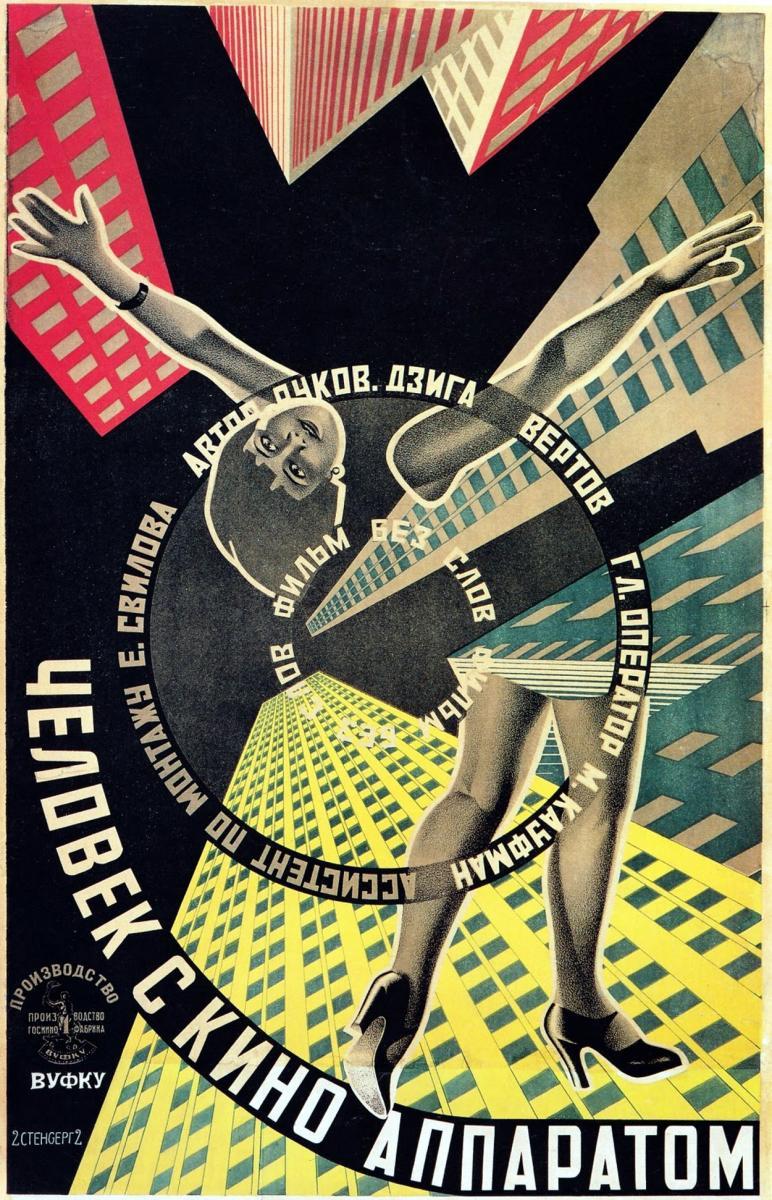

Man with a Movie Camera is a film with a forbidding reputation. It is generally described as a masterpiece, and its director, Dziga Vertov (1896-1954), is invariably acclaimed as one of the founding figures of documentary cinema. In public and critics’ polls, the film has frequently been voted the best documentary of all time, and one of the top ten films of any genre. Its approval ratings on sites like Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes indicate ‘universal acclaim’.

I first saw the film back in the late 1970s, as part of a Master’s course in Film Studies. As I recall, we watched the entire film in silence (as we did other silent films of the period); and we then spent several sessions of a study weekend poring over a 16mm. print on a Steenbeck editing suite (this was just before the advent of home video).

I first saw the film back in the late 1970s, as part of a Master’s course in Film Studies. As I recall, we watched the entire film in silence (as we did other silent films of the period); and we then spent several sessions of a study weekend poring over a 16mm. print on a Steenbeck editing suite (this was just before the advent of home video).

The film spoke to several key imperatives in academic Film Studies at the time: it was formally experimental and avant-garde, but it was also made in post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. Significantly, the then-fashionable director Jean-Luc Godard had named his working collective the ‘Dziga Vertov Group’ – producing films whose Maoist political radicalism was matched by their refusal to display ‘bourgeois’ aesthetic virtues such as narrative and entertainment. And the academic critics agreed: Man with a Movie Camera (hereafter, MWAMC) was a film that required lots of hard work. It needed to be viewed carefully, several times over, ideally on an editing desk, in order for its revolutionary artistic and political aims to be fully understood. Those were heady times.

I revisited the film late last year via the streaming platform MUBI, where it is still available at the time of writing. This version (restored in 2014) has a musical soundtrack performed by The Alloy Orchestra, created for the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, apparently ‘following the instructions of Dziga Vertov’.

This time around, my experience was much more pleasurable, and I’m sure the music played an important part in this. Vertov’s film is sometimes described as a ‘city symphony’, and some have suggested that it was influenced by earlier films such as Walter Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) – although Vertov very much wanted to be seen as a revolutionary artist, whose approach to film was entirely unprecedented. Before moving into documentary film-making, he had experimented with sound collages as part of his studies at Moscow’s Psycho-Neurological Institute, and was keen on the idea of ‘photographing sounds’. He went on to develop a ‘theory of intervals’ applied to film, and later studied metric patterns in Mayakovky’s poetry. MWAMC begins with a full orchestra getting ready to accompany the film in a film theatre, with the conductor and instrumentalists poised for the projector to roll; and there are several other scenes of music-making later on.

Yet music (or sound) barely features in academic analyses of the film. Even book-length studies, like Vlada Petrovic’s Constructivism in Film (1987) or Graham Roberts’s Man with a Movie Camera (2000), discuss elements like shot composition, camera movement and editing in incredible detail, yet barely mention music at all. And yet this was a film that was designed to be seen with musical accompaniment: it would not have been screened in complete silence, as it was when I first saw it.

The Alloy Orchestra version is by no means the first with a contemporary soundtrack: Wikipedia identifies no fewer than twenty different ones. Most notably, the classical composer Michael Nyman recorded a version in 2002, which is available on BFI video; and he was quickly followed by the British jazz/electronic ensemble The Cinematic Orchestra. The latter version can be found on YouTube here. (A good quality restoration of the film without music can also be found here.) These are both very effective; but in my view, the Alloy Orchestra soundtrack seems more in keeping with the time in which the film was made, although it too has some contemporary touches, and makes limited use of electronics.

In these musically-accompanied versions, the visual rhythms of the film – both of its editing and of the in-shot movement – are obviously much easier to follow. Through changing tempo and instrumentation, music helps to establish and shift the mood, to build momentum, and to underline the patterns of tension and release (or speeding up and slowing down in the editing and the movement) that recur throughout. The repetition and development of particular musical motifs also help the viewer grasp the underlying structure. In the process, the film comes across, not as forbiddingly avant-garde, but as playful, exuberant and positively entertaining: it seems full of energy and optimism, and even at times of humour and pleasure.

For much of the 1920s, Dziga Vertov had worked as a newsreel producer, making short films that were transported across the USSR on ‘agit trains’ to be shown to working-class audiences remote from the metropolis. Vertov and his colleagues (the ‘kinoks’ as they were known) were highly versed in the styles and preoccupations of the Western European artistic avant-garde. In particular, his work had much in common with the Italian futurist movement, sharing its interests in modern technology and industrialisation, and rejecting the moribund artistic conventions of the past. MWAMC has countless semi-abstract geometrical shots of machinery – pistons, gears, wheels, spools – that are very reminiscent of futurist painters like Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. However, Vertov’s aims were also political and educational, and his politics were very different from the futurists’: his films were intended as a form of propaganda, designed to reveal the scientific truths of socialism and to command the assent of the masses.

For much of the 1920s, Dziga Vertov had worked as a newsreel producer, making short films that were transported across the USSR on ‘agit trains’ to be shown to working-class audiences remote from the metropolis. Vertov and his colleagues (the ‘kinoks’ as they were known) were highly versed in the styles and preoccupations of the Western European artistic avant-garde. In particular, his work had much in common with the Italian futurist movement, sharing its interests in modern technology and industrialisation, and rejecting the moribund artistic conventions of the past. MWAMC has countless semi-abstract geometrical shots of machinery – pistons, gears, wheels, spools – that are very reminiscent of futurist painters like Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. However, Vertov’s aims were also political and educational, and his politics were very different from the futurists’: his films were intended as a form of propaganda, designed to reveal the scientific truths of socialism and to command the assent of the masses.

Vertov was a man with a mission: throughout his life, he was always writing manifestoes and theoretical justifications of his approach, and getting into vehement arguments with critics and other film-makers. Yet in the process, he was also struggling to deal with some fundamental tensions in his own work. On the one hand, he was a documentarist: he was committed to ‘capturing life unawares’, creating a record of reality by means of the ‘unplayed’ or ‘unstaged’ film – that is, without using actors or fictional stories or artificial sets or other trappings of the old-fashioned bourgeois cinema. And yet he was also a Marxist, who believed that the truth about society was largely hidden beneath the surface of reality, and that it was his job to reveal it. On the one hand was the ‘Kino-Eye’, the camera reflecting life as it was lived, objectively and without artifice; and on the other was ‘Kino-Pravda’ (cinematic truth), which could be revealed especially through montage (or editing). The camera was required to capture the reality of everyday life; but the resulting material also had to be manipulated in highly deliberate and elaborate ways.

However, this posed some significant challenges in terms of the audience. Vertov and his fellow kinoks argued that revolutionary politics required new ways of seeing and representing the world, and a more active role for film spectators. They aimed to shock audiences out of their comfortable bourgeois ways of viewing reality, by showing familiar things from new perspectives – or ‘making things strange’, as the formalist literary theorists of the time described it. Yet Vertov’s critics argued that the masses were not yet ready for this kind of stuff. At this immediately post-revolutionary moment in history, they suggested, film-makers still needed to make use of fictional stories and stereotypes in order to bring the uneducated population on side. Vertov’s work – and MWAMC in particular – was accordingly condemned for being inaccessible to the masses.

However, this posed some significant challenges in terms of the audience. Vertov and his fellow kinoks argued that revolutionary politics required new ways of seeing and representing the world, and a more active role for film spectators. They aimed to shock audiences out of their comfortable bourgeois ways of viewing reality, by showing familiar things from new perspectives – or ‘making things strange’, as the formalist literary theorists of the time described it. Yet Vertov’s critics argued that the masses were not yet ready for this kind of stuff. At this immediately post-revolutionary moment in history, they suggested, film-makers still needed to make use of fictional stories and stereotypes in order to bring the uneducated population on side. Vertov’s work – and MWAMC in particular – was accordingly condemned for being inaccessible to the masses.

Vertov saw his film as a kind of defence of documentary at a time when the tide of cultural politics was beginning to change; but by the end of the 1920s, it was clear that he had already lost this argument. Despite some limited critical acclaim, MWAMC was not widely distributed or seen in the Soviet Union. ‘Socialist realism’ became the official policy, and with the ascent of Stalin, Vertov was increasingly marginalised and ignored. While he did make some further films, he was eventually exiled to Ukraine and reduced to editing newsreels for the last twenty years of his life.

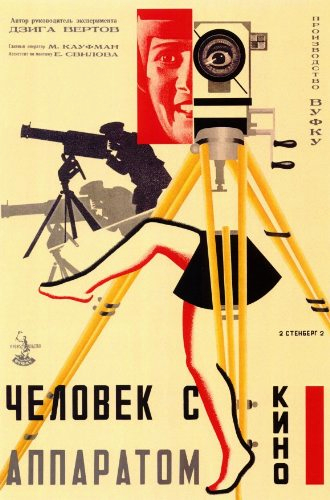

The opening titles of Man with a Movie Camera present it as ‘an experiment in the cinematic transmission of visible phenomena’: they declare that this is a film without intertitles, a script, sets or actors – a film that is ‘completely free from the language of theatre or literature’. Dziga Vertov is described as ‘the author-supervisor of the experiment’, alongside the cameraman, Mikhail Kaufman (who was his brother) and the editor, Elizaveta Svilova (his wife), who are both seen frequently as the film proceeds.

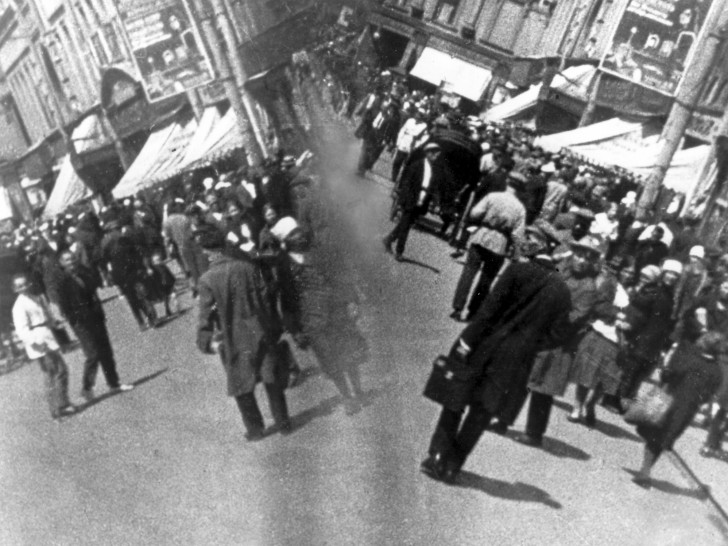

Yet for all these ‘experimental’ claims, the structure of MWAMC is quite straightforward. It follows a day in the life of a city – itself an amalgam of Moscow, Kiev and Odessa. Through six numbered sections (in this version), it shows the inhabitants of the city gradually waking up, going to work, dealing with various emergencies and life events (marriage, divorce, childbirth, death), and then relaxing after work, playing and watching sport and engaging in evening recreation.

Yet for all these ‘experimental’ claims, the structure of MWAMC is quite straightforward. It follows a day in the life of a city – itself an amalgam of Moscow, Kiev and Odessa. Through six numbered sections (in this version), it shows the inhabitants of the city gradually waking up, going to work, dealing with various emergencies and life events (marriage, divorce, childbirth, death), and then relaxing after work, playing and watching sport and engaging in evening recreation.

In line with Vertov’s theory of the ‘Kino-Eye’, the film makes use of newsreel material that he and his team had gathered across the preceding decade; and in doing so, it aims to provide a documentary record of this particular historical period in post-revolutionary Russia. In this respect, the film occasionally comes to resemble a kind of visual catalogue or taxonomy. Thus, in the category of ‘transport’, we have trams, trains, horse-drawn carriages, cars, buses, bicycles, ships, aeroplanes; under the category of ‘leisure’, we have exercising, sunbathing, drinking, playing board games, listening to music and dancing, and (of course) attending the cinema; under the category of ‘technology’, we have looms, telephone switchboards, steelworks, printing machines; and so on and so on. This is perhaps most tiresome when it comes to a ten-minute sequence of sports: in quick succession, we have pole-vaulting, hurdling, volleyball, football, high jumping, javelin, hammer-throwing, basketball, horse racing, motorcycle racing, weightlifting, swimming… The list starts to seem endless.

And yet this is also a film about film itself. Vertov’s description submitted to the state censors described it as ‘a film on the subject of film-making’; and the opening titles announce it as ‘an excerpt from the diary of a cameraman’. Thus, we see the cameraman leaving his apartment in the morning, toting his camera and tripod around the city, taking it down a mine, into a steelworks, and to the beach; and we see him filming several key shots from moving cars or high buildings or beneath railway tracks. We also see the editor organising the footage and splicing the strips of film together; and (at the beginning and end) we also see the film being projected to audiences in a movie theatre. By juxtaposing the activities of the film crew with those of ordinary workers – factory hands, miners, market traders, street cleaners – it shows that film-making is simply another kind of human labour (even if it doesn’t show us the economic basis of any of this).

And yet this is also a film about film itself. Vertov’s description submitted to the state censors described it as ‘a film on the subject of film-making’; and the opening titles announce it as ‘an excerpt from the diary of a cameraman’. Thus, we see the cameraman leaving his apartment in the morning, toting his camera and tripod around the city, taking it down a mine, into a steelworks, and to the beach; and we see him filming several key shots from moving cars or high buildings or beneath railway tracks. We also see the editor organising the footage and splicing the strips of film together; and (at the beginning and end) we also see the film being projected to audiences in a movie theatre. By juxtaposing the activities of the film crew with those of ordinary workers – factory hands, miners, market traders, street cleaners – it shows that film-making is simply another kind of human labour (even if it doesn’t show us the economic basis of any of this).

Equally, by showing the techniques by which the film was made – or, as formalist critics would have it, by ‘foregrounding the device’ – it also aims to demystify the process of representation. The film employs the full range of technical and visual devices available at the time. Again, in the spirit of the catalogue, we have: slow motion, accelerated motion, reverse motion, freeze-frames; pixillation, superimposition, split screens and kaleidoscopic effects; screens within screens, elements appearing and disappearing; and so on. The film plays with conventional patterns (shot/reverse shot; establishing shot/mid-shot/close-up); movement across and within shots is horizontal, vertical, diagonal, circular; and there are many visual ‘rhymes’, puzzles and jokes. We see events from several points of view: the cameraman, the participants, the editor, the audience or onlooker, the film-maker (who is filming the cameraman and the editor); and so on. While many shots do capture people ‘unawares’ or ‘off-guard’, as Vertov aimed to do, others very clearly show that his subjects were aware of the presence of the camera: some are embarrassed, while others play up to it. Far from being completely ‘unstaged’, parts of the film are definitely staged or re-enacted.

These elements undoubtedly account for much of the film’s appeal to film theorists. Writers like Vlada Petric (in Constructivism in Film) analyse the film in exhaustive (and exhausting) detail, literally frame-by-frame. Yet it was for similar reasons that MWAMC was condemned by some at the time for its ‘technical fetishism’: Vertov’s rival Sergei Eisenstein, for example, dismissed the film as mere formal ‘mischief-making’. However, Vertov’s use of these devices is by no means arbitrary or random. Part of the intention of his ‘experiment’ was to provide a resource, perhaps even a kind of ‘manual’, for future film-makers, as well as students; and it undoubtedly offers endless opportunities for those who have sought to develop a ‘grammar’ of film form or film language. While the film doesn’t explicitly show how all these effects are achieved, it does possess a strongly instructional purpose.

These elements undoubtedly account for much of the film’s appeal to film theorists. Writers like Vlada Petric (in Constructivism in Film) analyse the film in exhaustive (and exhausting) detail, literally frame-by-frame. Yet it was for similar reasons that MWAMC was condemned by some at the time for its ‘technical fetishism’: Vertov’s rival Sergei Eisenstein, for example, dismissed the film as mere formal ‘mischief-making’. However, Vertov’s use of these devices is by no means arbitrary or random. Part of the intention of his ‘experiment’ was to provide a resource, perhaps even a kind of ‘manual’, for future film-makers, as well as students; and it undoubtedly offers endless opportunities for those who have sought to develop a ‘grammar’ of film form or film language. While the film doesn’t explicitly show how all these effects are achieved, it does possess a strongly instructional purpose.

In a similar vein, contemporary critics (including the massively influential British documentary-maker John Grierson) accused the film of being ‘chaotic’ and of lacking ‘structure’: they argued that it was confused and aimless, a display of mere ‘self-satisfied trickery’. Yet this is very far from being the case. Many of the seemingly random shots and visual motifs in the opening few minutes are repeated and extended as the film proceeds. The topics of its six ‘chapters’ are clearly delineated; and the rhythmic patterns and pace of the editing (speeding up, slowing down) are also carefully managed. If anything, the film might be accused of being overly mechanical in its organisation – although the futurist in Vertov would probably have taken this as a compliment.

Nevertheless, the explicitly political dimensions of the film are somewhat more open to debate. If the film is aiming to provide what Vertov called ‘Kino-Pravda’ (film-truth) – a scientific representation of reality, in line with Marxist-Leninist principles – this is much less than obvious. One can read the film as a kind of hymn to the speed and efficiency of modern socialism, with its numerous shots of urban hustle and bustle, smooth-running machinery and happy smiling workers at work and play; although quite what is socialist about this is not entirely clear.

Equally, there are elements that don’t quite fit with this. We see many shots of (presumably bourgeois) women having beauty treatments, or being driven around in fashionable vehicles, alongside images of homeless people or derelicts sleeping in the streets, and dirty manual labour. Part of the sequence that focuses on leisure shows drunken behaviour at a pub, although the cameraman also seems to participate: at one point he is seemingly immersed in a mug of beer, and the camera later wobbles drunkenly. It could be that Vertov is implicitly condemning such behaviour, or encouraging us to do so; but when we see the more wholesome leisure pursuits in the ‘Lenin Club’ – such as shooting at Nazi targets – there are many fewer participants than there are in the pub. (Interestingly, many of the workers and other participants in the film are women – although equally Vertov does display a somewhat voyeuristic interest in women’s bodies, with revealing shots of women washing and getting dressed, sunbathing and bare-breasted mud-bathing, and in one instance, giving birth.)

Equally, there are elements that don’t quite fit with this. We see many shots of (presumably bourgeois) women having beauty treatments, or being driven around in fashionable vehicles, alongside images of homeless people or derelicts sleeping in the streets, and dirty manual labour. Part of the sequence that focuses on leisure shows drunken behaviour at a pub, although the cameraman also seems to participate: at one point he is seemingly immersed in a mug of beer, and the camera later wobbles drunkenly. It could be that Vertov is implicitly condemning such behaviour, or encouraging us to do so; but when we see the more wholesome leisure pursuits in the ‘Lenin Club’ – such as shooting at Nazi targets – there are many fewer participants than there are in the pub. (Interestingly, many of the workers and other participants in the film are women – although equally Vertov does display a somewhat voyeuristic interest in women’s bodies, with revealing shots of women washing and getting dressed, sunbathing and bare-breasted mud-bathing, and in one instance, giving birth.)

Some critics have struggled to identify specific political arguments here. Graham Roberts, for example, reads the film as a kind of coded critique of the more capitalistic tendencies of the New Economic Policy (NEP) introduced by Lenin in the early 1920s. Vlada Petric persistently interprets particular images as somehow symbolic of specific aspects of socialist ideology, but some of his readings are far-fetched and contentious. Of course, it’s possible that such meanings might have been obvious to contemporary viewers, although the film’s cool reception in the Soviet Union at the time gives some reason to doubt this. The film was accused, not only of ‘deforming facts’ – and hence betraying the documentary principle – but also of being obscure and unduly complex. MWAMC clearly fell foul of the imperative to be ‘intelligible to the millions’, and its apparent success with elite audiences in the West only seems to have confirmed this. (Interestingly, this view was shared by the eponymous ‘man’ himself, Vertov’s brother Mikhail Kaufman, who turned towards much more officially palatable forms of socialist realism in his own later films.)

In my view, Man with a Movie Camera is a much more enjoyable film than its reputation suggests – especially if it is watched with a musical accompaniment! It can certainly be seen as a defining early instance of documentary film, one that can be usefully set alongside the very different contemporary work of John Grierson or Robert Flaherty, for example. Its later influence is apparent, not just in documentary (for example in ‘cine-verité’) but also in music video; although I think that influence has probably been overstated. In some respects, it might be regarded as a kind of ‘limit case’ for documentary: an extreme or marginal instance that belongs in the outer reaches of the form. Indeed, if I can conclude with a question, it might be interesting to debate whether (or in what ways) the film is actually a documentary at all…

In my view, Man with a Movie Camera is a much more enjoyable film than its reputation suggests – especially if it is watched with a musical accompaniment! It can certainly be seen as a defining early instance of documentary film, one that can be usefully set alongside the very different contemporary work of John Grierson or Robert Flaherty, for example. Its later influence is apparent, not just in documentary (for example in ‘cine-verité’) but also in music video; although I think that influence has probably been overstated. In some respects, it might be regarded as a kind of ‘limit case’ for documentary: an extreme or marginal instance that belongs in the outer reaches of the form. Indeed, if I can conclude with a question, it might be interesting to debate whether (or in what ways) the film is actually a documentary at all…

READING

There are useful brief accounts of Vertov, and of Man with a Movie Camera, in Eric Barnouw’s classic history Documentary (New York, Oxford University Press, 1974) and in Patricia Aufderheide’s handy Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2007). Jeremy Hicks in Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film (London, I.B. Tauris, 2007) gives a valuable overview of Vertov’s whole career, covering many obscure films; while specific analyses of MWAMC can be found in Vlada Petric Constructivism in Film (Cambridge University Press, 1987) and Graham Roberts The Man with the Movie Camera (Tauris, 2000).