There is growing controversy about the banning of books from children’s libraries in the UK. What’s motivating this phenomenon, and what can we do about it?

There is growing controversy about the banning of books from children’s libraries in the UK. What’s motivating this phenomenon, and what can we do about it?

This coming week (5th-12th October 2025) is Banned Books Week in the UK. Suspended for several years in the wake of the pandemic, it is returning at a particularly appropriate time.

Just in the last few days, there has been a controversy about attempts to ban Angie Thomas’s young adult novel The Hate U Give at a school in Dorset. The single complainant, a parent at the school (and a former Conservative Party councillor), objected to the ‘explicit language’ and ‘sexual references’ in the book; but his main concern was about the book’s treatment of the issue of ‘race’. Accusing the school of a kind of reverse racism, he argued that ‘you should not be teaching this new form of Marxism to my children’. He also objected to the book Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman (a prescribed text for GCSE English exams): here again, the complaint focused on sexual themes, but it’s no coincidence that the book’s main character happens to be a migrant.

Just in the last few days, there has been a controversy about attempts to ban Angie Thomas’s young adult novel The Hate U Give at a school in Dorset. The single complainant, a parent at the school (and a former Conservative Party councillor), objected to the ‘explicit language’ and ‘sexual references’ in the book; but his main concern was about the book’s treatment of the issue of ‘race’. Accusing the school of a kind of reverse racism, he argued that ‘you should not be teaching this new form of Marxism to my children’. He also objected to the book Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman (a prescribed text for GCSE English exams): here again, the complaint focused on sexual themes, but it’s no coincidence that the book’s main character happens to be a migrant.

There has been a rise in such incidents recently. Back in July, the leader of Kent County Council – who represents the far-right Reform UK party – issued an instruction that all transgender-related books should be removed from children’s libraries. Again, the move came in response to a single complaint, and the outcome isn’t clear; but given Reform’s current standing in the opinion polls, the rhetoric is ominous.

Banning books has long been a favourite pastime for religious conservatives in the United States, but some have argued that it is increasingly crossing the Atlantic. For us in the UK, this might seem to be a relatively new front in the ongoing ‘culture wars’ in education. But is it really new, or just more visible than it used to be?

Censorship in various forms is as old as time. The Guardian’s list of banned publications goes back to Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (411 BC); while Wikipedia’s catalogue includes the Catholic Church’s Index Librorum Prohibitorum (which ran from 1560 to 1966). Political censorship covers the spectrum from the Nazis to the McCarthy era in the United States, through to the Soviet Union; while countless classics of literary modernism have been prosecuted for ‘obscenity’ (most notoriously in Britain, in the trial of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which I discuss here).

When it comes to books that have been banned specifically in schools, there are numerous lists of titles online, often accompanied by resumes and reviews. These include lists by the American Library Association and the writers’ organisation PEN America (which provides helpful ‘shop now’ links), as well as public libraries like the one in Edmonton, Canada (which allows you to check availability at your local branch).

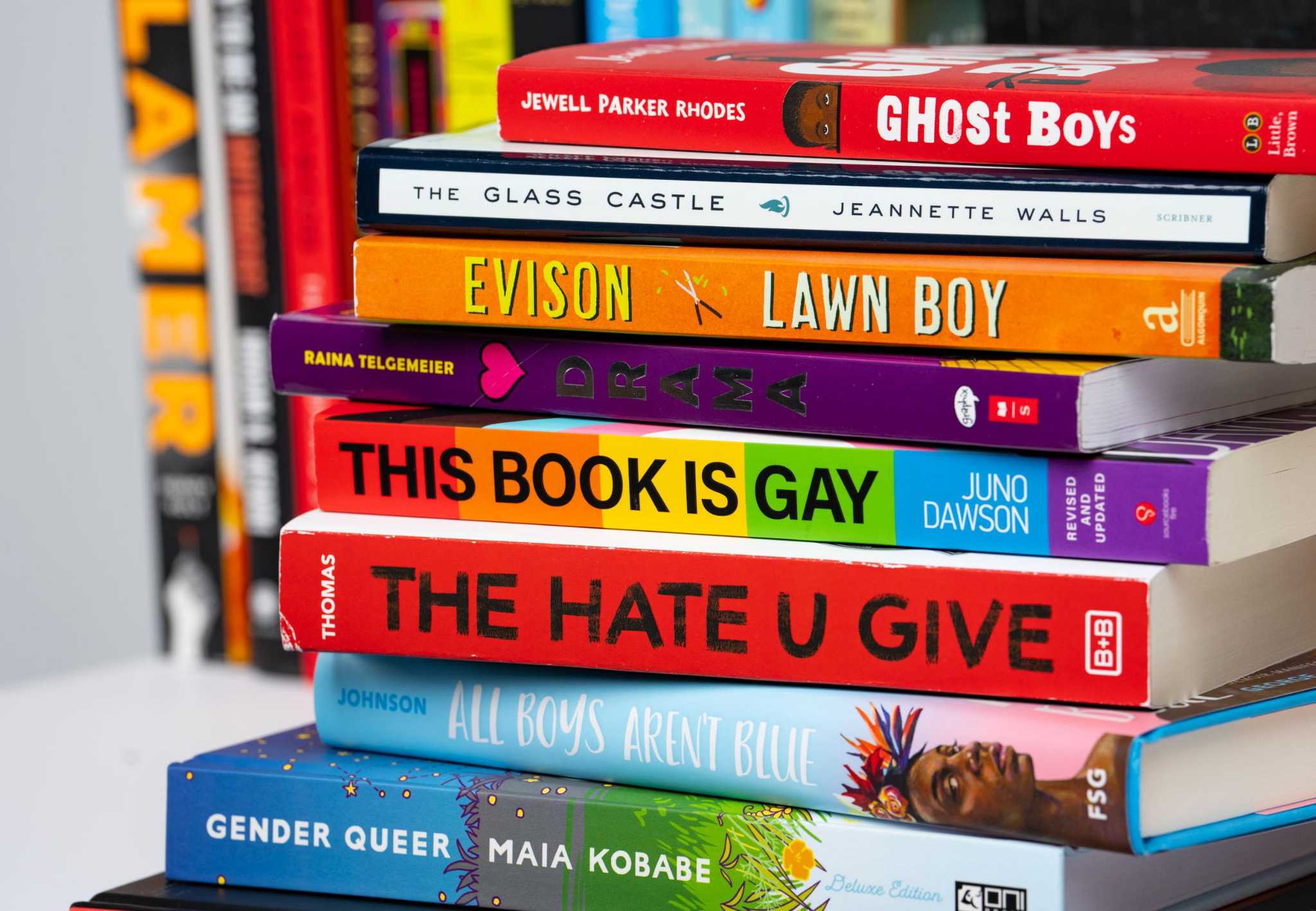

Titles targeted in the last couple of decades have included the Harry Potter books, The Catcher in the Rye, The Color Purple, The Bluest Eye, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Of Mice and Men, Slaughterhouse Five, Beloved, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, The Kite Runner and Native Son. Alongside such recognised literary classics, numerous young adult publications have become causes celebres – from Judy Blume’s Forever and other novels in the 1970s through to contemporary examples like The Hate U Give, Juno Dawson’s This Book is Gay and George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue.

The resumes in these lists reveal some of the more bizarre reasons why texts have been banned. Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel about the Holocaust, Maus, was challenged for showing naked mice. Jodi Picoult’s 19 Minutes – currently the most banned book in the United States – was convicted for a single mention of the word ‘erection’. Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was challenged for promoting homosexuality and cross-dressing; The Wizard of Oz for promoting socialist values; and Alice in Wonderland for encouraging drug use. As for Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, well, ‘trans propaganda’ is right there. Among the more compelling ironies here have been calls to ban dystopian novels which focus on censorship, such as 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale and Fahrenheit 451.

The resumes in these lists reveal some of the more bizarre reasons why texts have been banned. Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel about the Holocaust, Maus, was challenged for showing naked mice. Jodi Picoult’s 19 Minutes – currently the most banned book in the United States – was convicted for a single mention of the word ‘erection’. Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was challenged for promoting homosexuality and cross-dressing; The Wizard of Oz for promoting socialist values; and Alice in Wonderland for encouraging drug use. As for Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, well, ‘trans propaganda’ is right there. Among the more compelling ironies here have been calls to ban dystopian novels which focus on censorship, such as 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale and Fahrenheit 451.

As these titles suggest, there is a long history to all this. Herbert Foerstel’s book Banned in the USA, published in 2002, provides detailed accounts of several key cases from the late 1990s, while this Wikipedia article offers a really well-researched account of the early 2020s.

However, there is good evidence that book bans (or challenges) are on the increase in the United States. The American Library Association identified an eight-fold increase in such incidents, from 156 in 2021 to 1268 in 2023, although this dropped off slightly last year. These efforts are increasingly led not by individuals but by organised groups. What appear to be local initiatives led by ‘parents’ turn out to be driven by national advocacy organisations, such as the ironically-named ‘Moms for Liberty’, who are also busily challenging the school curriculum. More disturbingly, government officials, school boards and administrators are also playing an increased role; and one reason for last year’s drop-off may be that book bans have now become mandatory in several states.

It also appears that the focus of objectors’ concerns is shifting. Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, the Harry Potter books were frequently accused of promoting Satanism and ‘secular humanism’. More recently, these concerns have been largely superseded by accusations about ‘gender ideology’ and ‘equity ideology’, not to forget my personal favourite ‘cultural Marxism’. Under Trump, schools, universities and museums have been routinely condemned for promoting ‘critical race theory’, an academic approach that its opponents signally fail to understand.

It also appears that the focus of objectors’ concerns is shifting. Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, the Harry Potter books were frequently accused of promoting Satanism and ‘secular humanism’. More recently, these concerns have been largely superseded by accusations about ‘gender ideology’ and ‘equity ideology’, not to forget my personal favourite ‘cultural Marxism’. Under Trump, schools, universities and museums have been routinely condemned for promoting ‘critical race theory’, an academic approach that its opponents signally fail to understand.

As in the case of the Dorset school, assertions about obscenity or profanity often provide a convenient mask for more obviously political concerns – and (let’s be frank) for racism and homophobia. Books by Black authors or featuring Black characters are astonishingly well-represented on these lists. Put that together with a little ‘transgender ideology’ and notoriety would seem to be guaranteed.

Some of this is easy to ridicule, but it would be wrong to underestimate its impact on professional librarians, and of course on children. Kim Snyder’s documentary The Librarians (on limited release in the UK this week, and hopefully streaming soon) provides some truly frightening illustrations of this. Using interviews and footage of local school board meetings, she shows how censorship is increasingly impacting at a local level in states like Texas, Florida and Louisiana. Notably, she also explores the far-right ‘dark money’ that is funding national organisations like Moms for Liberty (which has its origins in the white supremacist John Birch Society, and began by targeting the wearing of masks in schools during the pandemic). Campaigners accuse librarians of peddling ‘pornography’, of being ‘paedophiles’ and of ‘grooming’ children; and the film features several librarians who have been publicly intimidated and attacked, issued with death threats, and lost their jobs for resisting state-wide book bans. For young people, libraries are no longer safe spaces; yet the film suggests that attacks on libraries are just the beginning of a much broader effort to spread far-right ideology to other levels of government.

Some of this is easy to ridicule, but it would be wrong to underestimate its impact on professional librarians, and of course on children. Kim Snyder’s documentary The Librarians (on limited release in the UK this week, and hopefully streaming soon) provides some truly frightening illustrations of this. Using interviews and footage of local school board meetings, she shows how censorship is increasingly impacting at a local level in states like Texas, Florida and Louisiana. Notably, she also explores the far-right ‘dark money’ that is funding national organisations like Moms for Liberty (which has its origins in the white supremacist John Birch Society, and began by targeting the wearing of masks in schools during the pandemic). Campaigners accuse librarians of peddling ‘pornography’, of being ‘paedophiles’ and of ‘grooming’ children; and the film features several librarians who have been publicly intimidated and attacked, issued with death threats, and lost their jobs for resisting state-wide book bans. For young people, libraries are no longer safe spaces; yet the film suggests that attacks on libraries are just the beginning of a much broader effort to spread far-right ideology to other levels of government.

In the UK, book banning has historically been perceived as less prevalent. But is that really the case? British readers of a certain age will probably recall the controversy around an illustrated children’s book called Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, about a five-year-old girl, her father and his boyfriend. Written by the Danish author Susanne Bosche, the book was translated into English in 1983 and published by the Gay Men’s Press. A few years later, it was reported that the book was available in children’s libraries in London. There was a press furore in which it was accused of being ‘homosexual propaganda’; and a so-called ‘Parents Rights Group’ called for the book to be burned.

In the UK, book banning has historically been perceived as less prevalent. But is that really the case? British readers of a certain age will probably recall the controversy around an illustrated children’s book called Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, about a five-year-old girl, her father and his boyfriend. Written by the Danish author Susanne Bosche, the book was translated into English in 1983 and published by the Gay Men’s Press. A few years later, it was reported that the book was available in children’s libraries in London. There was a press furore in which it was accused of being ‘homosexual propaganda’; and a so-called ‘Parents Rights Group’ called for the book to be burned.

After questions were raised about the book in parliament, this led directly on to the notorious Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which banned the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools as ‘a pretended family relationship’. Section 28 remained on the statute books until 2003, although it had a longer-lasting influence. While there were no successful prosecutions, it undoubtedly contributed to a climate in which educators became more cautious, and discrimination was legitimated (there is an obvious comparison here with current moves impacting on ‘illegal’ immigrants and on trans people).

A poster for the British Conservative Party from the 1987 General Election.

As this implies, the censorship is not necessarily always overt. There can be a chilling effect, where censorship is operating quietly, under the radar. Librarians might understandably decide to play safe in book selection, or to ensure that some books are not on display, or only available on request. A recent comparative study suggests that book censorship attracts less publicity in the UK than in the US, although it exists nonetheless. In relation to certain kinds of material, this study found that UK librarians were more actually likely to approve of censorship (and to practice it) than their US counterparts – although it is also notable that UK school librarians were significantly less likely to have had professional training.

Until recently, this kind of censorship in the UK has been more like background noise, although the cases I’ve mentioned do suggest that it is becoming more visible. Recent studies like this one by the librarians’ professional association CILIP and another by Index on Censorship have identified several recent cases where librarians have been overruled or forced to leave their jobs. Here again, challenges often appear to be mounted by individual parents, although in some cases they come from organisations unconnected to the schools in question. In one instance, a librarian was forced to cancel a talk by a gay author at her school in South East England following a post on a fundamentalist Catholic website in Scotland: she was obliged to leave, and the entire governing body (who supported her) was dismissed. Groups like the Safe Schools Alliance and Transgender Trend have been joined in this campaign by more broad-ranging far-right organisations like Turning Point UK and Patriotic Alternative. Predictably, the right-wing press also plays a leading role here; and such coverage almost entirely excludes the views of librarians, teachers, authors and young people themselves.

Thus far, research has been limited, and (unlike in the US) there is no centralised gathering of data; but what might be seen as a collection of isolated incidents is beginning to seem like a much broader problem. In the CILIP study, one third of librarians (albeit not only in schools or children’s libraries) said they had been asked to remove books, and over 80% said they were concerned about an increase in such incidents, predominantly relating to books featuring LGBTQ+ characters and/or themes of empire and ‘race’. And of course, these anxieties are also reflected in (and supported by) the government’s attempts to prevent discussion of gender identity in school sex education lessons, and to the rise and legitimation of far-right rhetoric on immigration. Last year, the School Library Association, along with CILIP and others, issued a joint statement on the issue, calling for clearer national guidance.

Especially when it comes to children, calls for books to be banned generally rest on familiar assumptions about media ‘effects’. In line with a broadly Romantic (not to say sentimental) view of childhood, children are seen as essentially innocent and vulnerable: they are passive consumers, blank slates on whom the media (and books) scrawl their harmful messages. This view is particularly prevalent in debates about visual media, where the mere presence of visual imagery seems to heighten the perception of danger. But in the campaigns for book banning, there appears to be a similar idea, that reading a book can in and of itself ‘turn you gay’ or encourage you to change sex. In the debates that led to Section 28, it was claimed that children should not be ‘indoctrinated into homosexuality’ or have it ‘thrust upon them’; and we’re now seeing similar arguments about ‘trans propaganda’. It seems as if mentioning or describing things automatically promotes them.

Especially when it comes to children, calls for books to be banned generally rest on familiar assumptions about media ‘effects’. In line with a broadly Romantic (not to say sentimental) view of childhood, children are seen as essentially innocent and vulnerable: they are passive consumers, blank slates on whom the media (and books) scrawl their harmful messages. This view is particularly prevalent in debates about visual media, where the mere presence of visual imagery seems to heighten the perception of danger. But in the campaigns for book banning, there appears to be a similar idea, that reading a book can in and of itself ‘turn you gay’ or encourage you to change sex. In the debates that led to Section 28, it was claimed that children should not be ‘indoctrinated into homosexuality’ or have it ‘thrust upon them’; and we’re now seeing similar arguments about ‘trans propaganda’. It seems as if mentioning or describing things automatically promotes them.

This might appear merely ridiculous, but it’s important to acknowledge that reading can be powerful, albeit in complex – and sometimes contradictory – ways. In the case of LGBTQ+ and ‘race’, this is partly a question of visibility. All children need opportunities to see people like themselves in the pages of a book; and this isn’t necessarily a matter of providing ‘positive images’ – for starters, it would be good to have any images at all. At the same time, it’s also about information – about having access to facts and ideas that might otherwise be hidden from view. Of course, in the absence of books, it’s now possible to access information about such issues online, although much of it is less than reliable, and it is not vetted for age-appropriateness. (I’ll return to these issues shortly.)

Ultimately, this should be seen as an issue of children’s rights. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example, asserts the child’s right to ‘seek, receive and impart information of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing, or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice’. (Notably, the Convention has never been ratified by the US government.) The difficulty, however, is that children’s rights frequently come into conflict with what are seen (and loudly proclaimed by some) as parents’ rights. We’re seeing increasing numbers of groups of parents who purport to speak on behalf of all parents – who don’t want their own children to read these books, but seem determined to extend that to other people’s children as well.

As ever, a good deal surely depends on the age of the children in question. It’s entirely reasonable that children should be directed towards material that is ‘age appropriate’. But what that means, and how we might establish it, is a very complex matter – especially in the absence of any real investigation of children’s own perspectives. It’s probably fair to expect that parents and children will have different estimations of what’s appropriate, but how do we adjudicate between them?

At the same time, there is some quite good evidence that the banning of books almost invariably leads to increased interest in them – in what is sometimes called the ‘forbidden fruit’ effect or the ‘Streisand’ effect (look it up!). Book bans in schools seem to result in sales ‘bumps’ and in increased requests in public libraries, particularly among children. They are particularly valuable for lesser-known authors, who might be forgiven for regarding them as a marketing technique. Such effects seem to extend widely beyond the immediate location of any ban, and even to places where there are no bans. Intriguingly, this study suggests that even if this counter-productive effect is known by the would-be banners, this doesn’t seem to stop them. This could suggest that challenging books in this way is more a matter of political symbolism: there is some evidence that in a polarized environment, it increases donations to right-wing parties who are keen to make the most of book ban events.

Self-evidently, the recent rise of book banning in schools is part of the culture wars of our times. It reflects broader attempts to reverse the limited advances made by LGBTQ+ people and by the civil rights movement. Add children and sex into the mix, and you have a powerful recipe for ‘homohysteria’ and racial resentment. Although we’ve seen some of this before, there are at least three aspects of wider context that make it particularly difficult to challenge right now.

Firstly, the issue has become caught up in the current weaponisation of ‘free speech’. Freedom of speech is no longer a concern confined to left-leaning libertarians: it has been aggressively taken up by powerful far-right figures, most notably Elon Musk. There is some glaring hypocrisy here. The far-right attacks ‘cancel culture’, yet (as in the case of school book bans, and increasingly in universities) it is aggressively promoting censorship. The rationale of free speech is used to justify the right of conservatives to be racist, misogynistic and homophobic; but those who speak back have to be silenced, preferably with the full force of the state. This hypocrisy has become even more evident in the wake of the killing of Charlie Kirk and the escalating war on Gaza.

Nevertheless, this issue cuts both ways. While contemporary moves towards censorship are being driven by the far-right, there are plenty of historical examples from the left. I can recall campaigns to ban the book Little Black Sambo (first published in 1899, but still available in children’s bookshops in the 1970s). Doctor Seuss, Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton have all been challenged at some point, especially for their crude racial stereotypes; while classics like Huckleberry Finn, To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men – all widely used in schools – have been banned for including racial slurs (or alternatively edited in order to remove them). In this context, ‘free speech’ is a concept that is in need of much more critical interrogation.

Nevertheless, this issue cuts both ways. While contemporary moves towards censorship are being driven by the far-right, there are plenty of historical examples from the left. I can recall campaigns to ban the book Little Black Sambo (first published in 1899, but still available in children’s bookshops in the 1970s). Doctor Seuss, Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton have all been challenged at some point, especially for their crude racial stereotypes; while classics like Huckleberry Finn, To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men – all widely used in schools – have been banned for including racial slurs (or alternatively edited in order to remove them). In this context, ‘free speech’ is a concept that is in need of much more critical interrogation.

The second difficulty is to do with the changing structures of the education system. One reason why book banning has been able to achieve so much traction in the United States is that control of education is almost wholly a matter for locally elected school boards. This opens the door, not just to individual activists but also to national organisations like Moms for Liberty who are ‘astroturfing’ campaigns so they appear to come from the grassroots.

This is not yet the situation in many other countries; but in the UK and elsewhere, the marketisation of the education system has significantly reduced the power of elected local education authorities. We now have a fragmented (and indeed chaotic) system, in which increasing numbers of schools – so-called ‘academies’ and ‘free schools’ – are no longer accountable to their local communities. Some (including large ‘chains’ of academies) are run by religious fundamentalists. For those who would seek to challenge censorship in schools, this may point to the need for a rather different style of counter-campaigning.

Thirdly, this is all happening in the context of wider cuts in the funding of libraries and in the provision of professionally trained librarians. These cuts are most evident in the escalating closures of public libraries, and particularly of children’s libraries, which are poorly funded and increasingly run by volunteers. However, they are also apparent in the decline of school libraries, which disproportionately affects children in disadvantaged areas. A recent report by the Great School Libraries campaign found that two-thirds of school libraries in Scotland have no budget at all, while in Wales, a quarter of schools don’t have a library. Over 77% of Welsh school libraries are not maintained by specialist staff. Northern Ireland schools were the least likely to have a school library, and those that did were the least likely to have a designated budget. Just this year, the city of Glasgow (the largest in Scotland, and the third-largest in the UK) was proposing to remove all the specialist librarians from its secondary schools.

Thirdly, this is all happening in the context of wider cuts in the funding of libraries and in the provision of professionally trained librarians. These cuts are most evident in the escalating closures of public libraries, and particularly of children’s libraries, which are poorly funded and increasingly run by volunteers. However, they are also apparent in the decline of school libraries, which disproportionately affects children in disadvantaged areas. A recent report by the Great School Libraries campaign found that two-thirds of school libraries in Scotland have no budget at all, while in Wales, a quarter of schools don’t have a library. Over 77% of Welsh school libraries are not maintained by specialist staff. Northern Ireland schools were the least likely to have a school library, and those that did were the least likely to have a designated budget. Just this year, the city of Glasgow (the largest in Scotland, and the third-largest in the UK) was proposing to remove all the specialist librarians from its secondary schools.

Just as librarians seem to be becoming fair game in the culture wars, they have been steadily deprofessionalised by governments. There is a lack of support for librarians in developing clear policies on responding to book challenges, and (perhaps even more than in the United States) school librarians are often isolated. As Alison Hicks proposes, librarianship has become a new form of ‘risk work’; and in this context, there is a need for new guidance and new ways of developing professional solidarity. Perhaps belatedly, there is some evidence that campaigns like Good School Libraries, along with the professional associations, are beginning to mobilise around these issues.

Finally, I should return to one of my ongoing concerns on this blog. Amid this debate, some have argued that books and libraries are now superfluous. Everything children need is on the internet these days. Let them use iPads!

Aside from any lingering attachments we may have to ‘old’ media, there are several significant problems with this argument. A significant proportion of young people still do not have adequate access to the internet, either in school or at home; and most of the material that is available online is not intended or designed for them. At the same time, there are growing attempts to restrict their use of digital media – for example by imposing constraints on ‘screen time’, bans on mobile devices, and age restrictions on social media. As I’ve argued before, Britain’s Online Safety Act is leading to unworkable and counter-productive efforts to curtail children’s access – which, among other things, are limiting their ability to locate reliable sex education information online.

Aside from any lingering attachments we may have to ‘old’ media, there are several significant problems with this argument. A significant proportion of young people still do not have adequate access to the internet, either in school or at home; and most of the material that is available online is not intended or designed for them. At the same time, there are growing attempts to restrict their use of digital media – for example by imposing constraints on ‘screen time’, bans on mobile devices, and age restrictions on social media. As I’ve argued before, Britain’s Online Safety Act is leading to unworkable and counter-productive efforts to curtail children’s access – which, among other things, are limiting their ability to locate reliable sex education information online.

Leaving it all to the internet would effectively cede control to the big technology companies, whose search engines and recommender systems are increasingly driven by unaccountable forms of artificial intelligence. Books are not inherently ‘better’ than other media, but they can do things other media are currently unable to do. For all the reasons I’ve suggested, children need books, and we should vigorously oppose attempts to censor them.