As the UK’s Online Safety Act begins to be implemented, some well-established critical questions are arising once again. Will we ever be able to prevent children accessing material that we deem to be harmful or objectionable? And if we can’t, what then?

As the UK’s Online Safety Act begins to be implemented, some well-established critical questions are arising once again. Will we ever be able to prevent children accessing material that we deem to be harmful or objectionable? And if we can’t, what then?

In the past week, the UK government has finally implemented one of the key provisions of the 2023 Online Safety Act (discussed previously on this blog). It places a duty on platform companies to introduce new safety measures aimed at children aged under 18, with the threat of eye-watering fines and the imprisonment of their senior managers if they fail to comply. In order to do this, companies are required to use ‘highly effective’ systems of age verification – although the Act itself does not fully specify what these should be. (For a useful summary of this aspect of the legislation, see here; and for the media regulator’s current efforts on enforcement, see here.)

In the past week, the UK government has finally implemented one of the key provisions of the 2023 Online Safety Act (discussed previously on this blog). It places a duty on platform companies to introduce new safety measures aimed at children aged under 18, with the threat of eye-watering fines and the imprisonment of their senior managers if they fail to comply. In order to do this, companies are required to use ‘highly effective’ systems of age verification – although the Act itself does not fully specify what these should be. (For a useful summary of this aspect of the legislation, see here; and for the media regulator’s current efforts on enforcement, see here.)

This is an international issue: Australia has recently introduced legislation to prevent under-16s from holding social media accounts (a ban that will, quite amazingly, extend to sites like YouTube); France is pushing for a similar ban to apply across Europe; while some US states are requiring age verification for material that is defined as ‘harmful to minors’. Bans on children using devices like mobile phones – not just in schools – are also being widely discussed. There’s no doubt that pressure on governments worldwide is significantly increasing.

Of course, there has been a very long history of attempts to restrict children’s access to media that are deemed (by adults) to be harmful. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato, who proposed to exclude the dramatic poets from his ideal Republic because of their dangerous influence on the young, was merely one of the first. This time around, we are told, the problem is so much more acute than it has ever been; and yet the campaigners seem to believe that they have finally found the foolproof way to keep children away from all that Bad Stuff. My argument here is not just that this isn’t going to work; it’s also that the overall strategy is misguided in first place, and does not serve children well.

One key problem here is that we run into an overlap, and possibly a conflict, between two types of regulation – on the one hand, content regulation, which is about restricting access to certain types of material; and on the other, regulation designed to preserve or guarantee users’ privacy (that is, data protection). Particularly where it involves gathering data about users’ identities, the requirement to regulate content cuts across the right to privacy – however hard that may be for MPs who have been caught accessing pornography in the houses of parliament. Some commentators argue – in my view convincingly – that banning children from access to the internet and social media is in fundamental violation of their human rights, not only to privacy but also to participation – and (in the words of the UN Convention) of the right ‘to be heard in decisions that concern them’.

One key problem here is that we run into an overlap, and possibly a conflict, between two types of regulation – on the one hand, content regulation, which is about restricting access to certain types of material; and on the other, regulation designed to preserve or guarantee users’ privacy (that is, data protection). Particularly where it involves gathering data about users’ identities, the requirement to regulate content cuts across the right to privacy – however hard that may be for MPs who have been caught accessing pornography in the houses of parliament. Some commentators argue – in my view convincingly – that banning children from access to the internet and social media is in fundamental violation of their human rights, not only to privacy but also to participation – and (in the words of the UN Convention) of the right ‘to be heard in decisions that concern them’.

Meaningful and effective legislation on these matters would need to establish three things. Firstly, the precise nature of the content that needs to be proscribed; secondly, the evidence that it’s actually harmful; and thirdly, ways of identifying the people to whom it is harmful, and when they are accessing it. I’ve had a lot to say about the first two points before (for example, in this short article), so I want to deal with them fairly briefly before moving on to the third.

Content

In terms of content, the current legislation seems to have two principal targets: firstly, pornography; and secondly, content likely to promote self-harm, suicide and eating disorders, or to result in bullying.

Pornography might seem to be an obvious, taken-for-granted category, but it really isn’t. Of course, material that describes itself as pornography is easy enough to identify: it’s the stuff on sites with names like ‘PornHub’ and ‘YouPorn’. This is material that is legal for adults to see; and it’s important to draw a clear line between this and child pornography, which is not – even if many campaigners tend to blur that line. However, there is also a good deal of material on mainstream sites that some people at least would regard as pornographic (some music videos on YouTube, for example). Defining what counts as pornography is increasingly problematic in the context of the mainstreaming of sexual imagery, or what some have called a general ‘pornification’ of culture.

On the other hand, not all sexual content (even ‘explicit’ content) is necessarily pornographic. There is a well-documented tendency for filters and other online blocking technologies to prevent access to material that is intended to be educational, or to offer advice – material that may well be of particular value to young people and to sexual minorities of various kinds.

On the other hand, not all sexual content (even ‘explicit’ content) is necessarily pornographic. There is a well-documented tendency for filters and other online blocking technologies to prevent access to material that is intended to be educational, or to offer advice – material that may well be of particular value to young people and to sexual minorities of various kinds.

This is perhaps even more difficult when it comes to content that is likely to lead to self-harm, suicide and eating disorders. This category is even more vaguely defined in the legislation. For example, when it comes to eating disorders, some sites are explicit about their aims – labelling themselves as ‘pro-ana’ or ‘pro-mia’ (pro-anorexia or pro-bulimia). However, such topics are routinely discussed on mainstream platforms, and in messaging groups. Those who produce or post such content, and those who use it, might justifiably claim that they are providing valuable advice and support, or even ‘empowering’ their users. On the other hand, there are countless websites and other media that promote unhealthy foods or super-skinny models, which reach vastly more people than pro-ana sites and the like (Frozen, anyone?). So how is such content to be identified in the first place? At the moment, it is hard to believe that AI will be capable of doing the job.

Harm

In both these instances – as in relation to other areas of media – evidence of harm is notoriously difficult to establish. Research on media effects is, to say the least, a contested field, beset by a great many challenging questions about theory and method. While campaigners are fond of asserting that the proof cannot be denied, most researchers know very well that this is far from the case. In the case of pornography, for example, there are some very significant limits to the evidence, particularly when it comes to claims about sexual violence. Like it or not, there is also a body of research that emphasises the benefits of pornography. Similarly, it’s far from clear whether the likes of pro-ana sites encourage eating disorders, or alternatively provide meaningful support for those who hope to overcome them. There is genuinely no scientific consensus on these matters, and it is wilful ignorance to claim that there is. (Martin Barker and Julian Petley’s book Ill Effects remains a useful and challenging source of debate here.)

Of course, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; and in situations where proof is hard to obtain, it may be wise to adopt the ‘precautionary principle’. But blanket bans, implemented by state regulators or by technology companies (or indeed by unreliable software) – rather than, for example, by parents in discussion with their children – would seem to be an excessive and potentially counter-productive response.

Of course, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; and in situations where proof is hard to obtain, it may be wise to adopt the ‘precautionary principle’. But blanket bans, implemented by state regulators or by technology companies (or indeed by unreliable software) – rather than, for example, by parents in discussion with their children – would seem to be an excessive and potentially counter-productive response.

(As an aside, it’s depressing to see how much of the research on children and media has come to be dominated by the either/or logic of these debates. Even the best researchers in the field seem to have been sucked into addressing very reductive questions about whether media (in general) are ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for children (in general). Reductive questions also lead to reductive methods, and thence to very limited kinds of evidence. Rather than calling for a better ‘balance’ between the negatives and the positives, we should surely be challenging the dichotomous terms of the whole debate, and trying to dial down the melodrama…)

Age assurance

The third problem here is equally difficult. It seems to be assumed that any concerns about harmful material do not apply to adults (which is probably a dubious assumption in some cases); although children are seen to be vulnerable by definition, simply because of their age. Yet if we want to prevent children from seeing such material, how do we identify the fact that they are children in the first place?

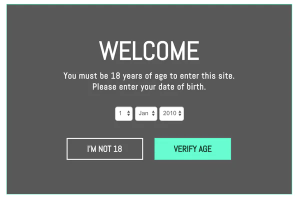

There are three main possibilities here. The first is self-declaration, which is the approach that most porn sites and social networks have operated to date. Here, users are merely required to tick a box to say they are over 18; or told that in continuing to the site, they are implicitly saying the same thing. For obvious reasons, such a system is almost wholly ineffective – although it might just possibly (and briefly) prevent some people from inadvertently stumbling across material they don’t wish to see.

There are three main possibilities here. The first is self-declaration, which is the approach that most porn sites and social networks have operated to date. Here, users are merely required to tick a box to say they are over 18; or told that in continuing to the site, they are implicitly saying the same thing. For obvious reasons, such a system is almost wholly ineffective – although it might just possibly (and briefly) prevent some people from inadvertently stumbling across material they don’t wish to see.

The second approach requires users to provide photographic verification of their age, for example by uploading a digital image, or even a ‘live’ selfie. Here too, there is considerable potential for defeating the system, by uploading an image of another person, or digitally altering one’s own image. Other methods involve the use of facial recognition technology to assess ‘live’ images, although the effectiveness of this is very dubious.

I tested this out by uploading a recent picture of myself to a couple of free sites that purport to be able to estimate your age. You can imagine my excitement at being told that I appear to be 40 years old. Let’s just say that I am considerably older than that. Of course, the system isn’t intended to deter the likes of me; so I went on to upload a picture of my five-year-old grandson. While the first site estimated his age as three, the second told me he was no less than thirty years old. These sites are likely to be using very similar AI to the services that are currently being relied upon by the platform companies. (I am anticipating shortly being targeted with a new wave of online advertising aimed at 30- and 40-year-old men.)

I tested this out by uploading a recent picture of myself to a couple of free sites that purport to be able to estimate your age. You can imagine my excitement at being told that I appear to be 40 years old. Let’s just say that I am considerably older than that. Of course, the system isn’t intended to deter the likes of me; so I went on to upload a picture of my five-year-old grandson. While the first site estimated his age as three, the second told me he was no less than thirty years old. These sites are likely to be using very similar AI to the services that are currently being relied upon by the platform companies. (I am anticipating shortly being targeted with a new wave of online advertising aimed at 30- and 40-year-old men.)

The third approach is perhaps the most rigorous, but even more problematic in terms of privacy. Here, users are required to provide some form of government-provided or government-approved photographic ID, such as a passport or a driving license. In some instances, they may have to upload an image of themselves holding the document in question.

Such a system might exclude children, but it would also exclude many adults. At the 2023 local elections, voters in the UK were required for the first time to produce photo ID at polling booths. The government’s own research showed that one in ten adults did not possess such a form of ID, effectively depriving them of the right to vote. (For that matter, around one third of UK adults don’t possess a credit card either.)

Unlike some other countries, the UK does not have a compulsory ID-card system, and governments have consistently fought shy of introducing one – primarily because of its dangerous implications for privacy and civil liberties. Proposals for a digital identity ‘wallet’ – which are now being actively developed both in the UK and across Europe – are open to similar criticisms. It’s not clear whether young people would only acquire such wallets at the age of 18; but I’m sure it won’t be long before somebody proposes that a digital tag or a chip should be compulsorily implanted in children’s bodies from birth.

Unlike some other countries, the UK does not have a compulsory ID-card system, and governments have consistently fought shy of introducing one – primarily because of its dangerous implications for privacy and civil liberties. Proposals for a digital identity ‘wallet’ – which are now being actively developed both in the UK and across Europe – are open to similar criticisms. It’s not clear whether young people would only acquire such wallets at the age of 18; but I’m sure it won’t be long before somebody proposes that a digital tag or a chip should be compulsorily implanted in children’s bodies from birth.

The potential here for unwarranted surveillance and for identity theft is obviously rampant; as is the level of distrust in government that any such system is likely to provoke. But my main point here is that, in the absence of a compulsory national system of identity verification, such forms of age assurance are most unlikely to be effective. To different degrees, all of these approaches might work to prevent five-year-olds inadvertently stumbling across content we might not want them to see; but they will do little to prevent determined – or merely inquisitive – teenagers.

Controlling the natives

Politicians often indulge in cliched rhetoric about ‘digital natives’, yet they seem uncomfortable with the idea that children might be more than able to work around the digital obstacles they place in their way. Of course, this partly depends on the age of the children in question. Banning children from having social media accounts (or indeed from accessing YouTube) might conceivably work if we’re talking about primary school kids; but banning those between 12 and 17 (who are not only, for the most part, more technologically savvy and more likely to be seeking information about ‘forbidden’ topics) seems unlikely to succeed.

Research studies have repeatedly pointed to the various loopholes and gaps that enable underage users to bypass age restrictions, and the worrying implications for children’s rights. Again, it should be noted that most of this research refers to young people aged under 13 – the legal age limit for many social media accounts – rather than under 16 or 18, the limit that is currently being imposed. One might reasonably expect teenagers to be much more adept at evading restrictions. Studies have also found that people in general tend to distrust government action in this area, not least because of the threats to privacy.

In the UK, one of the immediate consequences of the implementing of these regulations has been a boom in the interest in acquiring VPN software (a ‘virtual private network’, which enables people to use servers in a different national jurisdiction) or Tor browsers (anonymous search engines). Within a week of the new regulations being introduced, VPNs skyrocketed to the top of the charts in the App Store, and downloads of the free app ProtonVPN have apparently grown by almost 2000%. In a couple of clicks, I found step-by-step guides to installing and operating a VPN. Some have suggested that the government should now ban VPNs, although images of fingers in dykes come to mind. Ofcom already appears to be taking action against some companies that it suspects are not complying; but there are reportedly at least 14 million users of online porn in the UK, so the scale of the task is vast, if not impossible to manage.

In the UK, one of the immediate consequences of the implementing of these regulations has been a boom in the interest in acquiring VPN software (a ‘virtual private network’, which enables people to use servers in a different national jurisdiction) or Tor browsers (anonymous search engines). Within a week of the new regulations being introduced, VPNs skyrocketed to the top of the charts in the App Store, and downloads of the free app ProtonVPN have apparently grown by almost 2000%. In a couple of clicks, I found step-by-step guides to installing and operating a VPN. Some have suggested that the government should now ban VPNs, although images of fingers in dykes come to mind. Ofcom already appears to be taking action against some companies that it suspects are not complying; but there are reportedly at least 14 million users of online porn in the UK, so the scale of the task is vast, if not impossible to manage.

Even if larger companies seem to be falling into line, it’s uncertain how far regulators will be able to track activity on smaller or more obscure ‘niche’ sites – sites that are bound to proliferate precisely in response to the legislation. It’s likely that young people who are intent on seeking out prohibited material will be driven to search for it on the ‘dark’ web, thus potentially coming across much more disturbing content. Given the overall scale of the online porn industry, this will be inevitable; but the situation with regards to other allegedly harmful content is likely to prove even muddier.

It should be noted that we have been here before. Ten years ago, companies were eagerly rushing into the growing market for ‘parental control’ software. These packages were sold with big promises, but there was considerable evidence that children were very adept at working around them. As Nathan Fisk vividly shows in his book Framing Internet Safety, they found the use of such tools patronising, and the mutual mistrust between parents and children which they cultivated was less than constructive.

It should be noted that we have been here before. Ten years ago, companies were eagerly rushing into the growing market for ‘parental control’ software. These packages were sold with big promises, but there was considerable evidence that children were very adept at working around them. As Nathan Fisk vividly shows in his book Framing Internet Safety, they found the use of such tools patronising, and the mutual mistrust between parents and children which they cultivated was less than constructive.

At the time, I wrote an article about this, which is still available here. The article began by talking about new laws that would target ‘objectionable content’ online, and introduce age verification systems that seem almost identical to the ones of today. Those laws were eventually included in Part 3 of the 2017 Digital Economy Act, although it seems that they were never implemented – perhaps in recognition of some of the difficulties I’ve discussed here. The government responsible was, of course, led by David Cameron and Nick Clegg. And what happened to Nick Clegg? Well, he went on to work for Facebook…

Obviously, this is not a timeless debate. There are probably more ‘extreme’ forms of content available now (although there are significant historical and cultural variations in how we might define ‘extremity’). But by the same token, the means that one might use to restrict access to such content are much easier to defeat. It’s no longer a matter of denying physical access to cinemas showing X-rated movies, or scheduling potentially problematic content after the 9pm television ‘watershed’. By comparison, for today’s ‘digital natives’, getting around the constraints of the Online Safety Act would seem even easier.

Education

Let me be clear: I am not arguing that young people should have unrestricted access to online porn or other problematic content. Nor am I suggesting that we should not attempt to protect children. This is not an either/or question, despite campaigners’ attempts to make it so. (I can recall being asked by one high-profile campaigner in a public forum on this topic whether I was in favour of child abuse, or against it…) Rather, given that children are likely to encounter such material – and that this will continue to be the case despite the efforts to implement any ban – what should we do about this?

However we understand the problem here, more prohibitive legislation is not the answer. Complete safety or total protection is an impossibility. And there is no technical fix: as Ranum’s Law (coined by the software developer Marcus Ranum) would have it, ‘you can’t solve social problems with software’.

Education may well be part of the answer – as much, if not more, in the context of the home as in school. But here a moralistic, patronising approach is not the way to proceed (let alone mandated viewings of the Netflix drama Adolescence, as was seriously proposed by the British Prime Minister). As I’ve argued for many years, we need to begin from a much more informed and nuanced understanding of how young people make sense of the material they do inevitably encounter. We need to protect young people from things that might be dangerous, but we also need to prepare them to deal with the realities of adult life. And in this instance, that means we have to talk with them – and teach them – about pornography, however difficult that may be.

Education may well be part of the answer – as much, if not more, in the context of the home as in school. But here a moralistic, patronising approach is not the way to proceed (let alone mandated viewings of the Netflix drama Adolescence, as was seriously proposed by the British Prime Minister). As I’ve argued for many years, we need to begin from a much more informed and nuanced understanding of how young people make sense of the material they do inevitably encounter. We need to protect young people from things that might be dangerous, but we also need to prepare them to deal with the realities of adult life. And in this instance, that means we have to talk with them – and teach them – about pornography, however difficult that may be.

Among its many failings, the Online Safety Act doesn’t address education – and in fact barely mentions it. Amid growing interest in ‘media literacy’, this seems entirely inconsistent. Pornography and other forms of ‘objectionable content’ are self-evidently forms of media, and should logically be one focus of media literacy education. At the same time, the government would be better advised to focus its energies on supporting young victims of sexual harassment and abuse; and on providing sex education that focuses on consent and pleasure, and on what young people say they want and need to learn.

August 2025

Pingback: Protecting minors? Book bans are on their way to Britain | David Buckingham

Pingback: Teaching Adolescence: the antidote to ‘toxic masculinity’? | David Buckingham

Pingback: The ban on ‘digital childhood’ | David Buckingham