A forgotten best-seller of the mid-1950s sheds light on youth culture and the potential of creative youth work.

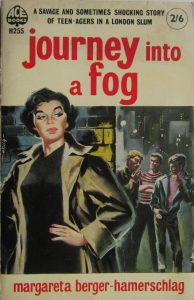

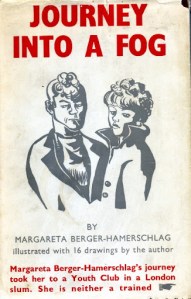

Exactly seventy years ago, a little-known Austrian artist published a book about her work teaching art to disaffected young people in London youth clubs. Surprisingly, the book became a best seller. Journey into a Fog by Margareta Berger-Hamerschlag was originally published in 1955 by the left-wing publishing house Gollancz. A paperback edition followed soon afterwards, its cover emblazoned with the headline ‘A savage and sometimes shocking story of teen-agers in a London slum’. The back cover blurb was written by one J.J. Mallon, the Warden of Toynbee Hall, a long-established charitable institution serving the poor of East London:

Exactly seventy years ago, a little-known Austrian artist published a book about her work teaching art to disaffected young people in London youth clubs. Surprisingly, the book became a best seller. Journey into a Fog by Margareta Berger-Hamerschlag was originally published in 1955 by the left-wing publishing house Gollancz. A paperback edition followed soon afterwards, its cover emblazoned with the headline ‘A savage and sometimes shocking story of teen-agers in a London slum’. The back cover blurb was written by one J.J. Mallon, the Warden of Toynbee Hall, a long-established charitable institution serving the poor of East London:

The most brilliant and alarming document of its kind. It calls attention, as no other book has done, to the existence of an epidemic of corruption and depravity which is eating into and destroying the sense of decency of innumerable boys and girls… I read it in two hours and will remember it for the rest of my life.

Journey into a Fog appeared at an interesting point of transition in the cultural history of post-war Britain, which I’ve written about several times before. The youth clubs Berger-Hamerschlag describes (which are set in ‘grim’, prison-like Victorian school buildings) are remarkably similar to the East London school in E.R. Braithwaite’s To Sir With Love (1959); and, even though she doesn’t use the term, the young people themselves are related to the ‘teddy-boys’ (and girls) who appear in Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy (1958) and Colin MacInnes’s Absolute Beginners (1959). This was also the period of Karel Reisz’s documentary The Lambeth Boys, and Relph and Dearden’s film Violent Playground.

The author’s role as a youth worker can also be compared with that of Hoggart’s protégé Ray Gosling (a journalist and later a TV documentary producer), and Arthur Chisnall, the founder of the famous rhythm-and-blues club on Eel Pie Island in Twickenham, West London. A little later, such young people were also a focus of concern in Stuart Hall and Paddy Whannel’s The Popular Arts, one of the foundational texts of media education in Britain.

Berger-Hamerschlag’s book preceded all of these, yet it has largely faded into obscurity (the university library had to retrieve it for me from an offsite store). However, its popularity and critical acclaim at the time can be taken as an early indication of what later researchers have called ‘the youth question’ in post-war Britain – and what would shortly become the focus of a significant moral panic about the scourge of ‘juvenile delinquency’. All this eventually led to the government founding the Albemarle Committee, whose report in 1960 resulted in the professionalisation of the youth service, and significant increases in funding.

Berger-Hamerschlag’s book preceded all of these, yet it has largely faded into obscurity (the university library had to retrieve it for me from an offsite store). However, its popularity and critical acclaim at the time can be taken as an early indication of what later researchers have called ‘the youth question’ in post-war Britain – and what would shortly become the focus of a significant moral panic about the scourge of ‘juvenile delinquency’. All this eventually led to the government founding the Albemarle Committee, whose report in 1960 resulted in the professionalisation of the youth service, and significant increases in funding.

However, the lurid promise of the book’s publicity belies the more complex and ambivalent nature of its content: this is not a sensational tale of ‘corruption and depravity’, or the destruction of ‘decency’, at least for this contemporary reader. It’s rather more interesting than that.

The ‘fog’ of the book’s title might well refer to the repeated fogs that shrouded London during this period (as discussed in Lynda Nead’s brilliant visual/cultural history, The Tiger in the Smoke). Yet it also aptly describes the author’s sense of disorientation, and her struggle to find a way of engaging her mostly reluctant students. To some degree, this was about her position as an exile in London; but it was also about class.

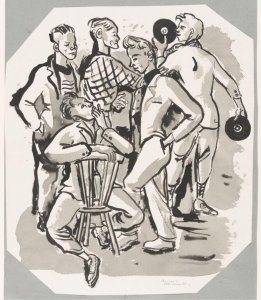

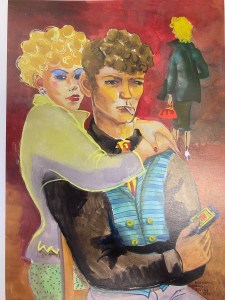

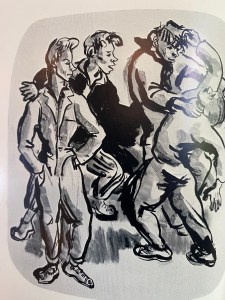

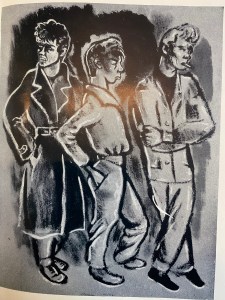

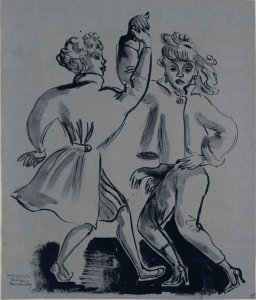

Margareta Berger-Hamerschlag was born in Vienna in 1902 to wealthy Jewish parents. From an early age, she attended children’s art classes taught by Franz Cizek (who influenced her later work in the youth clubs, and is cited in her book). In her teens, she went on to art school. She seems to have been an independent, progressive and cosmopolitan young woman. As an artist, she worked in a range of media, including woodcuts, oil and watercolour, as well as designing costumes and illustrating books and magazines. She had some success, participating in group exhibitions, but in 1936 she and her husband relocated to London, largely (it would seem) in response to the rise of Nazism. Her work is figurative rather than abstract, and is influenced by the ‘New Objectivity’ of the time (Otto Dix, George Grosz et al.). It’s probably at its most effective when picturing people, not least in her images of the youth clubs. (I’ve lifted a few of these here, but further examples of her work can be found on this website hosted by her son, and in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection here.)

Margareta Berger-Hamerschlag was born in Vienna in 1902 to wealthy Jewish parents. From an early age, she attended children’s art classes taught by Franz Cizek (who influenced her later work in the youth clubs, and is cited in her book). In her teens, she went on to art school. She seems to have been an independent, progressive and cosmopolitan young woman. As an artist, she worked in a range of media, including woodcuts, oil and watercolour, as well as designing costumes and illustrating books and magazines. She had some success, participating in group exhibitions, but in 1936 she and her husband relocated to London, largely (it would seem) in response to the rise of Nazism. Her work is figurative rather than abstract, and is influenced by the ‘New Objectivity’ of the time (Otto Dix, George Grosz et al.). It’s probably at its most effective when picturing people, not least in her images of the youth clubs. (I’ve lifted a few of these here, but further examples of her work can be found on this website hosted by her son, and in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection here.)

Although her husband was an architect, the couple were not wealthy. Margareta seems to have begun working in the youth clubs at the beginning of the 1950s partly because they were short of cash; although in the book she complains about the poor rate of pay, and seems to have purchased some of the art supplies she brought into her classes with her own money. However, Journey into a Fog was a great success: described by reviewers as ‘a shocker’ and as a ‘deeply sad, very remarkable book’, it was very positively reviewed, and ran to several editions (including in the USA). This enabled her to afford a house in Hampstead in North London (a somewhat more bohemian and less affluent area than it is today). However, Margareta died of cancer only a couple of years later, in 1958. (Further information, especially about the youth club work, and some good illustrations can be found in a booklet called ‘Beyond the Jiving’ by Mel Wright, produced to accompany an exhibition in London in 2008.)

Journey into a Fog is set in youth clubs run by the London County Council in working-class districts in North West London (Kilburn and Paddington). These were areas of poor housing, with high levels of crime. Most of the young people who attend the clubs appear to be trades apprentices, and to this extent they are beginning to earn some disposable income: yet the affluence celebrated by Prime Minister Harold Macmillan later in the decade (‘you’ve never had it so good’) is still a long way off. Crucially, these young people (aged between 14 and 20) were the children of the Blitz: some of them would have been evacuated, while others had lost parents in the War. Many of them have a continuing fear of war, not least due to what they hear about atomic weapons. (There are interesting parallels here with the ‘Covid generation’.)

Berger-Hamerschlag was clearly shocked by the deprived and unstable backgrounds of the young people she taught, and in some cases by their psychological distress. ‘It seemed to me another world indeed,’ she writes. The boys and girls are ‘bustling, young, and yet with joy curiously switched off as you might switch off a light; rather like an imitation of life, supposed to be richer and more gay, but with an underlying strain of pathetic sadness and resignation’.

Some of the young people she deals with suffer from serious illnesses, and many are described as ‘thin’ and ‘undernourished’. Most have never ventured outside the immediate neighbourhood, let alone into the countryside; and yet they are dangerously restless. Some are involved in knife fights and gang violence, and this spills over into the school. Attendance at the youth club is very erratic, and many of the students are clearly there to socialise rather than to make art. The girls seem to come primarily to accompany their boyfriends, and rarely participate. Students steal the fruit from her carefully arranged still lives; some start fires in the classroom; others threaten and sexually harass the teachers and the female students; some bring in pornography, and most of them swear profusely. One boy draws the same picture over and over again. A few students are clearly talented, but Berger-Hamerschlag struggles to sustain their interest. (For those of us who worked in inner city schools in the 1970s and 1980s, these accounts are probably very familiar – and rather less ‘alarming’ than they were for the book’s reviewers.)

Berger-Hamerschlag undoubtedly has a sense of her civilizing mission as an art teacher – and in this sense, her approach is not far removed from the ‘missionary’ approach of many English teachers at the time. She argues that the young people’s needs are not ‘purely material’, but a matter of ‘spiritual urgency’: the role of education, as she puts it, is ‘to wake up the dead’. Art might provide a way of helping them to discover their imagination and their inner values; it is ‘a proof that wholeness is possible’. ‘My aim,’ she writes, ‘is to lead them towards life, away from egotism, from hopelessness, from sympathy with death… I want to straighten their distorted picture of the world, make them feel, observe and express the new experience of its uniqueness.’

Even so, she refuses to conceive of teaching art in therapeutic terms, ‘as a sort of remedy for ills’. Nor does she have much time for what she regards as the false innocence of ‘child art’. While her classes make reference to classical traditions, it is not her aim to induct young people into an established canon of ‘great’ art. Nevertheless, there is a strong craft dimension to her teaching: she works hard to teach technique and the use of different media, and is not interested in what she calls the ‘hobby idea about art’.

As such, there is little indication of Berger-Hamerschlag attempting to engage with the youth culture of the time. Her pictures show boys in what she calls ‘spivvish attire’ with enormous quiffs, alongside heavily made-up girls in slit skirts and high heels, hanging out, jiving and sharing records. Yet even the dances are, she writes, ‘lifeless and dreary… in spite of the ear-splitting noise of the boogie-woogie music and the jerking about of their young limbs!’ They are ‘rather like a trance… the Bacchic feast of the joyless.’

As a teacher, Berger-Hamerschlag has little interest in giving the young people what they seem to want. She does attempt to engage the reluctant girls by getting them to create designs for a fancy-dress party and a fashion show, but these come to nothing; and she is harshly dismissive of the introduction of film screenings in the club, describing film as a ‘plague’. (The students are apparently shocked that she does not possess a television.) She has no time for the ‘Donald Duck’ comic illustrations and ‘pornographic’ film-star images that several students turn out, and she frequently tells them so. They need to produce work ‘of their very own’, out of the ‘experience of brain and heart’, rather than mere ‘copies’.

As a teacher, Berger-Hamerschlag has little interest in giving the young people what they seem to want. She does attempt to engage the reluctant girls by getting them to create designs for a fancy-dress party and a fashion show, but these come to nothing; and she is harshly dismissive of the introduction of film screenings in the club, describing film as a ‘plague’. (The students are apparently shocked that she does not possess a television.) She has no time for the ‘Donald Duck’ comic illustrations and ‘pornographic’ film-star images that several students turn out, and she frequently tells them so. They need to produce work ‘of their very own’, out of the ‘experience of brain and heart’, rather than mere ‘copies’.

In tones reminiscent of Richard Hoggart and F.R. Leavis, she bemoans their fascination with ‘the cheap substitute, the secondhand and artificial’ and the ‘false gloss and saccharine flavour’ they take from the ‘fairy-land’ of Hollywood. Their ‘main difficulty’, she asserts, is their attitude to sex, which is ‘pregnant with fear and self-accusation’, shame and disgust – and which she regards as a kind of legacy of Puritanism. With echoes of D.H. Lawrence, she rails against the young people’s ‘deadness’, ‘lethargy’ and ‘hopelessness’, and their lack of a ‘spiritual life’.

Even so, Berger-Hamerschlag is consistently sympathetic to the young people she works with. Both in the illustrations and in some of the written portraits, she pays close attention to their individuality and the difficulties of their lives. Crucially, her aim is not to integrate them into middle-class normality, but (in line, perhaps, with her progressive upbringing in Vienna) to cultivate their unique personalities, and even their rebelliousness and inclination to ‘mutiny’. The aim of teaching, she argues (in a very Leavisite formulation), should be to ‘show them new ways of life which could be conveyed through the few to the many’.

Journey into a Fog is by no means a simple, redemptive narrative of the heroic teacher winning round a group of recalcitrant youth, in the manner of To Sir With Love (or even Blackboard Jungle, for that matter). Still less is it an exercise in voyeuristic ‘class tourism’. As a teacher, Berger-Hamerschlag is no soft cookie. She upbraids the class for their ‘kindergarten behaviour’: ‘I want to deal with art students, not with five-year-old mentalities. I’d rather those who won’t play the game will go.’ Yet she becomes depressed about her ability to make progress, and resorts to ‘pills’ and ‘sea salt baths’; and she even fantasises about how she might escape if she won the football pools.

Right at the start of the book, she describes how, ‘after years of sustained struggle’, she has experienced a ‘miracle’ at one of the clubs, encountering students who are ‘eager, charming and friendly’ – although this seems to have occurred in the context of an art school rather than an elementary classroom. Yet the atmosphere of the youth club seems to deteriorate as the year goes on; and the ending of the book is far from a triumph over adversity.

Right at the start of the book, she describes how, ‘after years of sustained struggle’, she has experienced a ‘miracle’ at one of the clubs, encountering students who are ‘eager, charming and friendly’ – although this seems to have occurred in the context of an art school rather than an elementary classroom. Yet the atmosphere of the youth club seems to deteriorate as the year goes on; and the ending of the book is far from a triumph over adversity.

Jimmy, the leader of the club, is described in fairly ambivalent terms throughout. He seems to have a rather cynical view of the aims of the club – it is about ‘lion-taming’, he tells her, and it exists primarily to keep these young people off the streets, where they might cause much greater mischief. ‘He’s full of that amateur psychology which is now in everybody’s mouth and means nothing’, she asserts. However, Jimmy is also supportive of her work, and appears very popular with the students, even taking some of them off for drives in his car… Yet at the end of the book, his interest is revealed to be much less than benign: he is sacked for sexually molesting the young people, seemingly on a prolific scale. Berger-Hamerschlag herself is distraught; and, despite its optimistic beginning, the book ends on this moment of betrayal, failure and despair.

Journey into a Fog is undoubtedly a book of its time; yet it is one that deserves to be rediscovered. Despite its limitations, it comes much closer to the lived experience of young people than other, more celebrated accounts of the period. But it also has a contemporary relevance. The problems of Berger-Hamerschlag’s students continue to be faced by many young people today – perhaps especially in the aftermath of Covid. Yet youth work in Britain has been comprehensively decimated over the past fifteen years; and rates of mental ill-health among young people are rising precipitously. I used to work in an inner London youth centre that was open five days a week from the end of school until nine or ten in the evening. That would be unthinkable today. A little while ago, I was listening to a rather depressing discussion on the radio about youth clubs. What might youth clubs involve, the participants were asking. Probably more than table-tennis, one suggested. And what would be the point of them? If we’re having to ask these questions now, something is surely very wrong indeed.