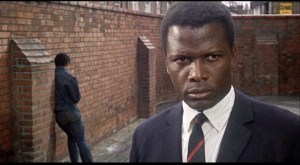

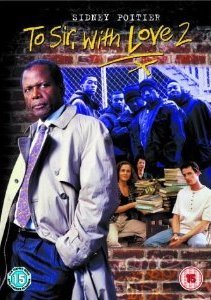

E.R. Braithwaite’s To Sir With Love, published in 1959, tells the story of a black teacher and his struggles to succeed in a largely white secondary school in one of London’s poorest neighbourhoods. It was translated into several languages, and in 1967 adapted as a Hollywood feature film, directed by Richard Clavell and starring Sidney Poitier. A made-for-TV sequel, To Sir With Love 2, in which Poitier resumes his role teaching in a school in Chicago, followed in 1996.

E.R. Braithwaite’s To Sir With Love, published in 1959, tells the story of a black teacher and his struggles to succeed in a largely white secondary school in one of London’s poorest neighbourhoods. It was translated into several languages, and in 1967 adapted as a Hollywood feature film, directed by Richard Clavell and starring Sidney Poitier. A made-for-TV sequel, To Sir With Love 2, in which Poitier resumes his role teaching in a school in Chicago, followed in 1996.

To Sir With Love is part of a longer history of ‘heroic teacher’ narratives: it shows how an inexperienced and untrained teacher manages to win over – and ultimately to rescue – a group of disadvantaged and recalcitrant students. The book also has a great deal to say about ‘race relations’ – the often-troubled relationships between the white British population and a new and growing group of immigrants, especially from former colonies in the Caribbean. It’s a book that is often seen to convey positive moral messages, especially for young people: I first encountered it as a class reader in my school English lessons in the late 1960s.

Introducing E.R. Braithwaite

E.R. (Edward Ricardo) Braithwaite was born in 1912 in the colony of British Guiana (now Guyana). His family were members of a small black colonial elite. Both his parents had been educated at Oxford, and his father was a gold and diamond miner. He studied at the country’s top private school, and subsequently at City College in New York. During the Second World War, he served in the British Royal Air Force; and on being demobbed, he completed a Master’s degree in physics at Cambridge University.[1]

Despite his outstanding qualifications and experience, and numerous applications, Braithwaite was unable to find employment in his chosen profession of engineering. In To Sir With Love, he describes how on several occasions, he would be granted an interview, but then told that the position was filled once it became evident that he was black. Eventually, and without much initial commitment, he accepted a job ‘somewhat accidentally’ as a secondary school teacher in London’s East End. He taught there from 1950 to 1957.[2]

Despite his outstanding qualifications and experience, and numerous applications, Braithwaite was unable to find employment in his chosen profession of engineering. In To Sir With Love, he describes how on several occasions, he would be granted an interview, but then told that the position was filled once it became evident that he was black. Eventually, and without much initial commitment, he accepted a job ‘somewhat accidentally’ as a secondary school teacher in London’s East End. He taught there from 1950 to 1957.[2]

To Sir With Love has been somewhat neglected in accounts of the literature of the period, and even in studies of what is sometimes called the West Indian ‘literary renaissance’. It’s possible that the book was simply too popular to merit serious academic attention; but in several other respects, it is rather at odds with the emerging post-colonial writing of the time.[3]

Braithwaite himself worked in academia in later life, but there is little evidence that he was part of the literary world at this point. Unlike Caribbean authors like Sam Selvon, V.S. Naipaul, Andrew Salkey and others, who had migrated to the ‘mother country’ in the decade after the War, he was not intending to become a writer, any more than he intended to become a teacher. He was not a literary modernist, nor was he interested in formal experimentation. Unlike many of these writers, he was not looking back to his  country of origin; nor indeed did he become centrally involved in the emerging Black British cultural and political movements of the time. In fact, after a few years as a social worker, he moved to Paris in 1960 to begin a successful career as a diplomat and an educational consultant, and never returned to live in Britain.

country of origin; nor indeed did he become centrally involved in the emerging Black British cultural and political movements of the time. In fact, after a few years as a social worker, he moved to Paris in 1960 to begin a successful career as a diplomat and an educational consultant, and never returned to live in Britain.

Braithwaite later worked for UNESCO and the United Nations, and for the Guyanese government. He subsequently became an academic in the United States, eventually settling in Washington D.C. His later books included a memoir of his time as a social worker, Paid Servant (1962), the novel Choice of Straws (1965), and an account of his time in South Africa as a guest of the apartheid government, Honorary White (1975). He died in 2016 at the age of 104.

Introducing To Sir With Love

To Sir With Love is probably best seen as a memoir rather than a novel. The narrator and central character is called ‘Ricky Braithwaite’ (although he is given a different name in the film), and his experiences largely mirror those of its author – although there’s undoubtedly some ‘fictionalisation’ at work. Where the film has a clear narrative momentum, the book digresses into areas that are probably more of interest to social historians than those seeking character development or dramatic incident.

In the early chapters, we follow the narrator’s first arrival at Greenslade school in the docks area of East London. (Like the characters in the book, I will refer to the narrator as ‘Ricky’, in order to differentiate him from the author himself.) Despite his complete lack of experience and training as a teacher, he is instantly given a job teaching the older students – an occurrence that was not at all unusual at the time, especially in ‘difficult’ schools. Several chapters then track backwards to describe Ricky’s early experiences of arriving in Britain, and (following demobilisation from the RAF) his difficulties in finding work as an engineer.

In the early chapters, we follow the narrator’s first arrival at Greenslade school in the docks area of East London. (Like the characters in the book, I will refer to the narrator as ‘Ricky’, in order to differentiate him from the author himself.) Despite his complete lack of experience and training as a teacher, he is instantly given a job teaching the older students – an occurrence that was not at all unusual at the time, especially in ‘difficult’ schools. Several chapters then track backwards to describe Ricky’s early experiences of arriving in Britain, and (following demobilisation from the RAF) his difficulties in finding work as an engineer.

The book then returns to the account of his experiences as a teacher: it follows his attempts to impose discipline on the students, and how he eventually adopts a new approach. In the course of this, he has to deal with one of the girls, Pamela Dare, developing a romantic crush on him; he confronts the leading male disruptive influence, Denham, eventually defeating him in a boxing bout; he intervenes on behalf of another student, Fernman, who is arrested and charged with a knife attack; and he helps a dual-heritage student, Seales, cope with the death of his mother. There is also an extensive sub-plot about his romance with one of the teachers, the middle-class Gillian Blanchard. He meets her parents, who agree reluctantly that they can be married, although her father continues to be sceptical about the difficulties that their children might eventually face.

Representing education

To Sir With Love is obviously a book about education, although in fact it provides relatively little detail about the matter. There is some information about the headteacher’s educational philosophy, particularly his refusal to allow corporal punishment, and the scepticism of some of the teachers on this issue. The students are required to write ‘reviews’ of their lessons, and participate in a school council, which is described in detail in one chapter. These were innovative ideas at the time. The character of the headteacher, Mr. Florian, is apparently based on Alex Bloom, who was the headteacher of Braithwaite’s own school, and has since been recognised as one of the leading progressive educators of the post-War period.[4]

Ricky’s own approach is rather different. While he initially sticks to the official curriculum, working through the textbooks, he loses his temper when he arrives one day to find the girls are burning a sanitary towel in the classroom grate. This prompts a pedagogical breakthrough: he recognises that his students are effectively ‘adults’, who will be leaving school and embarking on adult life within a matter of months, and he changes his teaching style accordingly. He becomes insistent on politeness and courtesy: the girls are to be addressed as ‘Miss’, and the boys will be called by their last names. The students are encouraged to smarten up their appearance, avoid swearing, and eschew slovenly behaviour. At the same time, the formal curriculum will be abandoned: Ricky leaves behind the textbooks, and tells the students that from now on, they will be having open and even ‘informal’ discussions of topics that will matter to them in their adult lives. A significant turning point comes when he arranges for the class to take the day out of school in order to attend an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Nevertheless, this reversal of fortune happens remarkably quickly and painlessly – indeed, implausibly so. It is effectively complete after a couple of months, by the mid-way point of the book – beyond which the focus shifts to individual students and to Ricky’s romance with Gillian, and we see much less in the way of pedagogy. The students do initially display some challenging behaviour – they slam doors, bang desk lids, and throw books around – but they largely seem to obey his instructions from the start (as a former teacher educator, I have been in classrooms that are much more chaotic than this). We are told that Ricky comes to ‘respect’ his students, even ‘love’ them, as they do in return; and a distinction is made between his approach and that of the sadistic, bullying physical education teacher, Mr. Bell. But precisely how he achieves this in the classroom – and indeed, what goes on in Ricky’s new curriculum – remains fairly vague.

Nevertheless, this reversal of fortune happens remarkably quickly and painlessly – indeed, implausibly so. It is effectively complete after a couple of months, by the mid-way point of the book – beyond which the focus shifts to individual students and to Ricky’s romance with Gillian, and we see much less in the way of pedagogy. The students do initially display some challenging behaviour – they slam doors, bang desk lids, and throw books around – but they largely seem to obey his instructions from the start (as a former teacher educator, I have been in classrooms that are much more chaotic than this). We are told that Ricky comes to ‘respect’ his students, even ‘love’ them, as they do in return; and a distinction is made between his approach and that of the sadistic, bullying physical education teacher, Mr. Bell. But precisely how he achieves this in the classroom – and indeed, what goes on in Ricky’s new curriculum – remains fairly vague.

In this respect, it’s probably more useful to consider the book (and the film) in the wider context of fictional representations of teaching.[5] To some extent, it could be seen as a further instance of a familiar ‘charismatic teacher’ narrative: in the cinema, for example, we could point to Goodbye, Mr. Chips, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Dead Poets Society or even School of Rock. In such narratives, the teacher typically presents their own persona as a kind of role model for the students. This approach is often seen to result in easy and rapid success: teaching is represented as a kind of calling, and good teachers are shown as ‘naturals’, who are born rather than made (or indeed trained). All the films I’ve mentioned take place in elite private schools, which allow space for teachers’ eccentric individuality, even if those in charge struggle to contain it. Despite these teachers’ apparent abandonment of the traditional curriculum, and their more informal pedagogy, this often results in merely a different kind of authoritarianism.

Yet while Ricky Braithwaite does undoubtedly come to the rescue of his students, he doesn’t quite fit this charismatic mould. He is upstanding and powerful, but also somewhat restrained; he doesn’t dominate the classroom through sheer force of personality. To Sir With Love seems to me to belong in a rather different tradition, of what we might call the missionary teacher. Here, a determined individual sets out to overcome the resistance of a group of economically disadvantaged students, and to show them a path to some kind of knowledge and enlightenment – and he typically has to buck the system in order to do so. Blackboard Jungle would be one paradigmatic example; while films like Dangerous Minds and Stand and Deliver provide more recent treatments of the same theme.[6] The teachers here are often less than charismatic, but they are driven by a wider social mission, of the kind that Ricky begins to discover as the book proceeds. As is the case in To Sir With Love, the heroes of such narratives typically have to win a violent confrontation with the most challenging male student; and they generally build up to a moment of pedagogical breakthrough, where the teacher discovers the correct means of ‘getting through’ to the recalcitrant class.

As Dan Leopard suggests, there are some parallels here between the figure of the missionary teacher and the colonial anthropologist – which is most notable in their opening scenes or chapters, where the hero ventures warily into the foreign country of the working-class school.[7] Working class youth – physically mature, sexually provocative, media-fixated, difficult to manage – are presented almost as ‘natives’ or even ‘savages’, whose curious customs have to be understood before their circumstances can be ameliorated. This was a tone that was also characteristic of a good deal of sociological discourse about the ‘youth problem’ at the time[8]; and of course of the growing moral panics that attended the apparent rise of ‘uncontrolled’ youth culture.

However, the obvious difference in the case of To Sir With Love is that the racial roles are reversed. Ricky Braithwaite is not the white saviour seeking to rescue disadvantaged black and ethnic minority students, as is the case in Dangerous Minds, for example. On the contrary, the students here (with one exception) are all white, and he is black – although he is also paradoxically upper middle-class, and (as I’ve implied) a kind of colonialist as well. As we’ll see, the class issue is significantly altered in the film, where the teacher (re-named Mark Thackeray) speaks of his background working in dead-end jobs. I’ll explore this issue in much more detail in due course.

However, the obvious difference in the case of To Sir With Love is that the racial roles are reversed. Ricky Braithwaite is not the white saviour seeking to rescue disadvantaged black and ethnic minority students, as is the case in Dangerous Minds, for example. On the contrary, the students here (with one exception) are all white, and he is black – although he is also paradoxically upper middle-class, and (as I’ve implied) a kind of colonialist as well. As we’ll see, the class issue is significantly altered in the film, where the teacher (re-named Mark Thackeray) speaks of his background working in dead-end jobs. I’ll explore this issue in much more detail in due course.

Self-evidently, these are idealised representations. They may influence wider public perceptions of the teaching profession, but in my experience they are less than helpful for teachers themselves. Although To Sir With Love has been used in teacher training courses – where it can provide a useful resource (along with others) to explore questions of teacher identity[9] – it offers relatively little insight into the processes of teaching and learning. Teachers know that the realities of teaching and schools are much more constrained, and more mundane – and that success is much more difficult to achieve. They also recognise that effective teachers do not have to be individualists, but need to work as members of a team.[10] While such narratives may offer them short-lived inspiration, they could easily lead to disillusionment over the longer term.

Representing ‘race’, class and gender

In many respects, what the book has to say about ‘race’ is more interesting than what it says about education. As I’ve suggested, Braithwaite himself was a member of an elite colonial class, educated in the US as well as Britain. He had little in common with fellow Caribbean migrants, for example as represented in Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners or even Colin MacInnes’s London novels like City of Spades.[11] Ricky, the book’s narrator, has ‘grown up British in every way’, inspired by a belief in ‘the British way of life’ – an ideal of fairness, tolerance and freedom that, he argues, dominates the legal and governmental systems of colonial countries, as well as their culture and fashion (35-38).[12]

And yet ‘it is wonderful to be British,’ he tells us, ‘until one comes to Britain’. The London Ricky encounters is a long way from the London of his dreams, as is evident from his first impressions:

I suppose I had entertained some naively romantic ideas about London’s East End, with its cosmopolitan population and fascinating history. I had read references to it in both classical and contemporary writings and was eager to know the London of Chaucer and Erasmus and the Sorores Minories. I had dreamed of walking along the cobbled Street of the Cable Makers to the echoes of Chancellor and the brothers Willoughby…

But this was different. There was nothing romantic about the noisy littered street bordered by an untidy irregular picket fence of slipshod shopfronts and gaping bomb sites. (5)

Ricky’s disillusionment extends to his attitude towards many of the inhabitants of the city as well. Certainly at the start of the book, he displays a patrician disdain for the British working class. We first meet him on a London bus, on the way to an interview for his teaching job, where he encounters a group of ‘noisy, earthy charwomen’ whom he compares to ‘peasants’. He smiles at ‘the essential naturalness of these folk’, but from a position that he clearly regards as much higher up the social ladder (1, 3).

He displays a similar attitude towards the children who are to be in his charge. Rather than neat, well-mannered students seated in rows, he finds a ‘menagerie’. While the students are keen to emphasise their burgeoning (albeit vulgar) sexuality in their clothing, they are also ‘soiled and untidy’ (10). The girls’ inability to apply make-up correctly gives them a ‘tawdry, jaded look’, while the boys’ ‘scruffier, coarser, dirtier’ style disguises a kind of ‘planned conformity’ – it is ‘a symbol of toughness as thin and synthetic as the cheap films from which it was copied’ (47).[13]

If Ricky’s disdain for the great unwashed clearly reflects a particular class position, ‘race’ complicates matters significantly. While his students do occasionally refer to this issue – Denham, the leading delinquent, even calls him a ‘f—ing black bastard’ (although he ignores this) – their position is seen to be as much a reflection of ignorance as of racial hatred. The students (like their teachers), Ricky avers, had been taught using textbooks that reinforced ‘the concept that coloured people were physically, mentally, socially and culturally inferior to themselves, though it was rather ill-mannered to actually say so’ – and as such, these prejudices were ‘not entirely their fault’ (96). One of the key moments of tension in the book occurs when the students, having collected money to buy a floral wreath for the funeral of Seales’s mother, are unwilling to actually deliver it, for fear of gossip among the community if they were seen ‘going to a coloured person’s home’; but here too, overt racism is something that is seen to be more apparent among their parents’ generation than among the students themselves. One of the teachers, Weston, makes occasional innuendoes about Ricky’s skin colour – he is a ‘black sheep’ who probably uses ‘black magic’ to control his class; but Weston’s cynicism also makes him something of an anomaly among the staff.

If Ricky’s disdain for the great unwashed clearly reflects a particular class position, ‘race’ complicates matters significantly. While his students do occasionally refer to this issue – Denham, the leading delinquent, even calls him a ‘f—ing black bastard’ (although he ignores this) – their position is seen to be as much a reflection of ignorance as of racial hatred. The students (like their teachers), Ricky avers, had been taught using textbooks that reinforced ‘the concept that coloured people were physically, mentally, socially and culturally inferior to themselves, though it was rather ill-mannered to actually say so’ – and as such, these prejudices were ‘not entirely their fault’ (96). One of the key moments of tension in the book occurs when the students, having collected money to buy a floral wreath for the funeral of Seales’s mother, are unwilling to actually deliver it, for fear of gossip among the community if they were seen ‘going to a coloured person’s home’; but here too, overt racism is something that is seen to be more apparent among their parents’ generation than among the students themselves. One of the teachers, Weston, makes occasional innuendoes about Ricky’s skin colour – he is a ‘black sheep’ who probably uses ‘black magic’ to control his class; but Weston’s cynicism also makes him something of an anomaly among the staff.

Yet while racism is perhaps not the primary factor in Ricky’s experience as a classroom teacher, it plays a major role in his experience outside school. Indeed, it appears to override social class. Thus, while he partly accepts the headmaster’s argument that the children’s ‘difficulties’ are to do with poverty, he also finds it irritating:

My own experiences during the past two years invaded my thoughts, reminding me that these children were white: hungry or filled, naked or clothed, they were white, and as far as I was concerned, that fact alone made the difference between the haves and the have-nots. (25)

When he goes on to describe those experiences, it becomes clear that Braithwaite’s primary target – and one of the key reasons for his disillusionment – is the kind of genteel racism he encounters in the wider society. The book recounts what seems to have been Braithwaite’s own experience as an RAF airman – in which he apparently encounters very little prejudice. Yet once he starts to look for employment, he faces obstacles that are undoubtedly due to the colour of his skin. Similar problems arise when he seeks accommodation near the school, and he chooses to remain with a kindly white couple in Essex, some distance away. Ricky himself is immaculately dressed and well spoken, a stickler for politeness, and an upstanding moralist – in effect, a perfect English (or at least colonial) gentleman. Yet he is persistently excluded by the host population on the grounds of his ‘race’; and his response is not to protest, but to learn ‘what it means to live with dignity inside my black skin’ (145).

His experiences in Britain contrast markedly with those in the United States, where he was educated:

I have yet to meet a single English person who has actually admitted to anti-Negro prejudice; it is even generally believed that no such thing exists here. A Negro is free to board any bus or train and sit anywhere, provided he has paid the appropriate fare; the fact that many people might pointedly avoid sitting near to him [as occurs at a couple of points in the book] is casually overlooked. He is free to seek accommodation in a licensed hotel or boarding house – the courteous refusal which frequently follows is never ascribed to prejudice. The betrayal I now felt was greater because it had been perpetrated with the greatest of charm and courtesy. (38)

Despite all this, the book says very little about the Black British experience – and although (as we’ll see) the film seeks to say more, it does so in quite negative terms. As I’ve implied, Braithwaite himself felt he had relatively little in common with the largely working-class immigrants of the Windrush generation. With the exception of Seales, who has a white mother and a black father, there are no other black characters in To Sir With Love.

‘Race’ thus intersects with class here in sometimes paradoxical ways. Although it’s a less prominent theme, gender is also part of the equation. Ricky clearly finds his students’ display of sexuality rather unnerving, if not disgusting – but this is especially the case with the girls. His new classroom regime is distinctly gender-normative: the girls are to be referred to in traditional courtly terms (as ‘Miss’), while the boys are called by their surnames. While the boys are encouraged to smarten up, Ricky is especially keen to provide guidance on physical appearance and ‘deportment’ for the girls, and asks some of the female teachers to help him with this. The girls are urged to avoid ‘slovenly’ or ‘sluttish’ behaviour: it is their sexuality that is represented as a problem, not that of the males.[14] Ricky’s authority over the class is ultimately achieved when, despite his reluctance, he joins the ’king-pin’ Denham in a boxing bout and defeats him. Ricky may be outwardly chaste (an issue I’ll discuss shortly), but there is little doubt about his superior masculinity.

‘Race’ thus intersects with class here in sometimes paradoxical ways. Although it’s a less prominent theme, gender is also part of the equation. Ricky clearly finds his students’ display of sexuality rather unnerving, if not disgusting – but this is especially the case with the girls. His new classroom regime is distinctly gender-normative: the girls are to be referred to in traditional courtly terms (as ‘Miss’), while the boys are called by their surnames. While the boys are encouraged to smarten up, Ricky is especially keen to provide guidance on physical appearance and ‘deportment’ for the girls, and asks some of the female teachers to help him with this. The girls are urged to avoid ‘slovenly’ or ‘sluttish’ behaviour: it is their sexuality that is represented as a problem, not that of the males.[14] Ricky’s authority over the class is ultimately achieved when, despite his reluctance, he joins the ’king-pin’ Denham in a boxing bout and defeats him. Ricky may be outwardly chaste (an issue I’ll discuss shortly), but there is little doubt about his superior masculinity.

The politics of ‘race’

For some contemporary critics, Braithwaite’s position on the politics of ‘race’ was problematic; and as we’ll see, these criticisms were even more apparent in responses to the film. One notable instance of this can be found in an article by F.M. Birbalsingh published in the Caribbean Quarterly in December 1968. The article is presented as a review of the book, and of a couple of others that followed it: it isn’t clear whether Birbalsingh’s criticisms were somehow implicitly reinforced by the film, which appeared in 1967, although curiously he does not mention it (although he does refer to two other Sidney Poitier films of the same year).[15]

According to Birbalsingh, To Sir With Love promotes a fundamentally individualistic version of racial politics. Ricky succeeds implausibly quickly as a teacher, but the causes of his students’ delinquency are not investigated: Braithwaite fails to address the fundamental structural dimensions of racism. In Birbalsingh’s view, the book is merely a ‘sordid demonstration of the author’s own vanity’ – and indeed of his ‘effervescent self-congratulation’. Ricky never dissents from others’ estimation of him as an exceptionally talented teacher. Among other evidence, Birbalsingh quotes a paean of praise from one of his colleagues, Mrs. Dale-Evans:

‘Then along comes Mr. Rick Braithwaite. His clothes are well cut, pressed and neat; clean shoes, shaved, teeth sparkling, tie and handkerchief matching as if he’d stepped out of a ruddy bandbox. He’s big and broad and handsome. Good God, man, what did you expect? You’re so different from their fathers and brothers and neighbours. And they like you; you treat them like nice people for a change. When they come up here for cookery or needlework all I hear from them is ‘Sir this, Sir that, Sir said…’ until I’m damn near sick of the sound of it.’ (107)

‘Then along comes Mr. Rick Braithwaite. His clothes are well cut, pressed and neat; clean shoes, shaved, teeth sparkling, tie and handkerchief matching as if he’d stepped out of a ruddy bandbox. He’s big and broad and handsome. Good God, man, what did you expect? You’re so different from their fathers and brothers and neighbours. And they like you; you treat them like nice people for a change. When they come up here for cookery or needlework all I hear from them is ‘Sir this, Sir that, Sir said…’ until I’m damn near sick of the sound of it.’ (107)

‘Astonishingly’, Birbalsingh writes, Ricky is not at all embarrassed by this ‘absurd panegyric’: it is as though his innate superiority is simply being recognised. According to Birbalsingh, Braithwaite presents his narrator as an exception to the rule: as a ‘rather talented and thoroughly civilized’ black man, he should be accepted as being as good as the whites. He is ‘as British as the British themselves’, and prejudice against him is unfair, because of his social accomplishment, not because of his basic humanity. Implicitly, Birbalsingh argues, Braithwaite is urging West Indians ‘to re-shape themselves in a British image’ – to learn to fit in, to assimilate, rather than to protest.

There is some truth in Birbalsingh’s criticisms. The book – and more explicitly, the films – espouse a quietist philosophy of self-control and non-violence in the face of racism. At several points, we see Ricky consciously avoiding confrontation on this point; and in some instances, it is left to white women to address the issue. Thus, it is the other teachers who challenge Weston’s racist insinuations. When Ricky becomes the subject of disapproving comments by white women on the train on the way to the museum, it is Pamela Dare who challenges them; and she does the same when Ricky is accidentally cut, and one of the students expresses surprise that he has red blood – ‘what did you expect, fat boy? Ink?’ (103). In the book, Gillian is exasperated by his failure to confront the racist treatment the couple have received in a restaurant: ‘why did you just sit there and take it?’ she shouts, ‘Just who do you think you are, Jesus Christ?’

When one of the students is bullied by the sadistic gym teacher, Mr. Bell, Ricky advises them that fighting back is not the answer; and he even urges one of the students, who has confronted Bell, to apologise to him. Most notably, Ricky advises the dual-heritage student Seales to avoid violence in responding to those who would ‘push him around’: ‘one thing I learned,’ he says, ‘is to try always to be a bit bigger than the people who hurt me’ (156-8). (In To Sir With Love 2, this non-violent philosophy is explicitly reinforced by the photograph of Martin Luther King which Thackeray puts on the classroom wall, and the way the students invoke ‘passive resistance’ (in line with what he has taught them about the civil rights movement) when he is dismissed.)

However, Birbalsingh’s criticisms also seem unduly harsh. Ricky learns a good deal – not only about the lives of his students, but also about the politics of social class – in the course of the narrative. The patronising colonial disdain he displays at the beginning of the book is dissipated by the end. He also learns that ultimately he will never be regarded as an exception: simply because of the colour of his skin, he will never be able to escape the realities of racism, although he may be able to address them in small, incremental ways as a teacher. Thus, where we do see evidence of his teaching, he is clearly endeavouring to inform his students about the real nature of life in other countries, and about the effects of imperialism (95-6). As John McLeod suggests, there may also be some fleeting glimpses of an alternative, multicultural or post-colonial view, in the character of Gillian (who, given her fluency in Yiddish and her ‘olive skin’, may in fact be Jewish – although this is not the case in the film) and perhaps even in the character of Seales (whose role in the book is rather different from the film, as we’ll see).[16] Taken as a whole, the book cannot be read simply as an endorsement of the colonialist position with which Ricky starts out.

However, Birbalsingh’s criticisms also seem unduly harsh. Ricky learns a good deal – not only about the lives of his students, but also about the politics of social class – in the course of the narrative. The patronising colonial disdain he displays at the beginning of the book is dissipated by the end. He also learns that ultimately he will never be regarded as an exception: simply because of the colour of his skin, he will never be able to escape the realities of racism, although he may be able to address them in small, incremental ways as a teacher. Thus, where we do see evidence of his teaching, he is clearly endeavouring to inform his students about the real nature of life in other countries, and about the effects of imperialism (95-6). As John McLeod suggests, there may also be some fleeting glimpses of an alternative, multicultural or post-colonial view, in the character of Gillian (who, given her fluency in Yiddish and her ‘olive skin’, may in fact be Jewish – although this is not the case in the film) and perhaps even in the character of Seales (whose role in the book is rather different from the film, as we’ll see).[16] Taken as a whole, the book cannot be read simply as an endorsement of the colonialist position with which Ricky starts out.

Interestingly, there are signs that Braithwaite’s own politics had moved on by the mid-1960s. In a powerful article, published in Spring 1967 (and thus before Birbalsingh’s critique), he offers an explicitly political analysis of the plight of the ‘coloured immigrant’ and of the operation of racism in Britain, which takes in housing, employment and welfare provision as well as education. He describes how, after the War, the British people were challenged by those (like him) who understood themselves to be ‘equally British’, and expected to be treated as such: their response was ‘to close ranks and to isolate the intruder in every way possible’.[17] He goes on to discuss how the issue of immigration was weaponised by right-wing politicians in the early 1960s: prejudice and ‘illiberal attitudes’, he writes, are now openly expressed ‘with pride and an air of respectability’ (the parallels with Britain today hardly need to be emphasised). At this point, Braithwaite would have been aware of the rise of the Black Power movement in the United States, and he is pessimistic about the idea that the ‘coloured immigrant’ will ever achieve ‘full responsible citizenship’ in British society. His argument here goes well beyond the more individualistic, quietist approach of To Sir With Love: the action he appears to recommend is based on collective solidarity, rather than dignified silence and turning the other cheek, and he warns of violent confrontations to come.

Enter Sidney Poitier

At which point, enter Sidney Poitier. Despite the international success of the book, several Hollywood studios had eventually decided to pass on a film adaptation of To Sir With Love. This may have derived from a discomfort with the mixed-race romance (which I’ll consider below), but it may also have reflected an uncertainty about how to market a film set in working-class London to an American audience. It was not until 1966 that Columbia was able to get the project off the ground, with James Clavell (previously known mainly as a screenwriter) coming on board as director.[18]

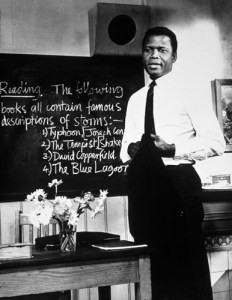

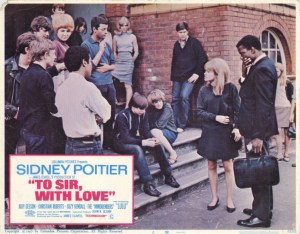

Sidney Poitier was undoubtedly the leading black actor of the period – indeed, he was the only black star who might be counted upon to ensure a degree of box-office success for a seemingly unlikely proposition.[19] In many respects, Poitier appeared to be perfect for the central role: he was tall, upstanding and dignified. Even so, the film was allocated a comparatively small budget ($750,000); and the distributors seemed ill-prepared for its success. The film was released in June 1967, a few months ahead of Poitier’s starring roles in the crime drama In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison) and then the light comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (dir. Stanley Kramer). This was the commercial peak of Poitier’s career – but it was also the point at which the critics began to turn against him.

Sidney Poitier was undoubtedly the leading black actor of the period – indeed, he was the only black star who might be counted upon to ensure a degree of box-office success for a seemingly unlikely proposition.[19] In many respects, Poitier appeared to be perfect for the central role: he was tall, upstanding and dignified. Even so, the film was allocated a comparatively small budget ($750,000); and the distributors seemed ill-prepared for its success. The film was released in June 1967, a few months ahead of Poitier’s starring roles in the crime drama In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison) and then the light comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (dir. Stanley Kramer). This was the commercial peak of Poitier’s career – but it was also the point at which the critics began to turn against him.

Poitier had played many roles since his screen debut at the start of the 1950s, including (significantly in this case) as an at-risk youth in another school movie, Blackboard Jungle (dir. Richard Brooks, 1955), as well as leading parts in the musical Porgy and Bess (dir. Otto Preminger, 1959) and a version of black author Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun (dir. Daniel Petrie, 1961). He was the first black actor to win an Academy Award, for his role in Lilies of the Field (dir. Ralph Nelson, 1963); and by the mid-1960s, he was the biggest male box-office draw in the country.

As an actor, Poitier was generally cast as the idealised, non-threatening black, whose high achievement, flawless morality, and sheer likeability enabled him to embody the professed values of ‘white society’ better than many whites themselves. In In The Heat of the Night, he plays an unimpeachable Philadelphia detective who takes a stand against the corruption and ineptitude of the white Southern police; while in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, he is a paragon of virtue and all-round excellence who cannot fail to be accepted by the parents in an inter-racial marriage.

Privately, Poitier’s politics may have been different, or more nuanced: he was certainly conflicted over some of the idealised roles he was required to play, yet he was unwilling to take on parts as evil or violent characters for fear of pandering to negative stereotypes. Sexuality was a particular problem here, especially because of whites’ fears of miscegenation: Poitier was frustrated by the general lack of a romantic or sexual dimension in his screen roles. For the only major-league black actor of the time, the ‘burden of representation’ weighed very heavily on his shoulders.

However, by 1967 this ‘positive images’ strategy, and the liberal anti-racism that it embodied, was starting to appear more problematic. This was a year of widespread ‘race riots’ across the United States, and the rise of Black Power. Against this background, Poitier’s film persona seemed old-fashioned: the figure of the ‘well-adjusted, useful Negro’ that was intended to quell white anxieties was no longer seen to be relevant to changing times. Critics (both black and white) judged Poitier’s idealised image to be bland and one-dimensional, and lacking in complexity. Some argued that there were troubling continuities with earlier representations: the critic Hollis Alpert accused Poitier of being ‘the Stepin Fetchit of the sixties’, while Catherine Sugy described him as ‘Uncle Tom refurbished’. In a high-profile article in the New York Times, black playwright Clifford Mason argued that Poitier was merely a ‘showcase nigger’, and a tool of the white establishment.[20]

However, by 1967 this ‘positive images’ strategy, and the liberal anti-racism that it embodied, was starting to appear more problematic. This was a year of widespread ‘race riots’ across the United States, and the rise of Black Power. Against this background, Poitier’s film persona seemed old-fashioned: the figure of the ‘well-adjusted, useful Negro’ that was intended to quell white anxieties was no longer seen to be relevant to changing times. Critics (both black and white) judged Poitier’s idealised image to be bland and one-dimensional, and lacking in complexity. Some argued that there were troubling continuities with earlier representations: the critic Hollis Alpert accused Poitier of being ‘the Stepin Fetchit of the sixties’, while Catherine Sugy described him as ‘Uncle Tom refurbished’. In a high-profile article in the New York Times, black playwright Clifford Mason argued that Poitier was merely a ‘showcase nigger’, and a tool of the white establishment.[20]

These criticisms peaked in responses to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, a film that in some respects takes these aspects of the Poitier icon to an extreme: paradoxically, in a film that is essentially a romantic comedy about ‘race’, the Poitier character is not only sexless (there is just one fleeting kiss) but also curiously race-less as well. Some of the critical responses to To Sir With Love, released six months earlier, were equally damning. The film was accused of being ‘simple-minded’ and a ‘Pollyanna story’; and critics expressed exasperation at the leading character’s ‘platitudes’ and ‘moralistic cliches’. The influential (white) critic Pauline Kael inveighed against Poitier’s ‘saintly, sexless’ persona – ‘the ideal boy-next-door-who-happens-to-be-black’.[21]

From page to screen

E.R. Braithwaite himself apparently loathed the film adaptation of his book: ‘I detest the movie from the bottom of my heart’, he later said – although the royalties undoubtedly came in useful.[22] His criticisms may have been partly motivated by the omission of the inter-racial romance between Ricky (renamed Mark Thackeray in the film) and Gillian Blanchard, which I’ll discuss in due course.

In addition to Poitier’s involvement, the film shows some other signs of being addressed to a US audience. At the very start, Thackeray’s bus journey to Wapping implausibly takes him past a series of holiday-postcard London landmarks (Big Ben, Tower Bridge): presumably the East End location would have been unfamiliar and unexpected to most US viewers. Meanwhile, the film also features the pop singer Lulu playing a fairly prominent role as one of the students, ‘Babs’ Pegg, and singing the sickly title song (which later topped the US charts) no fewer than three times; while the second-division British group The Mindbenders – who had reached number one, and toured America, a couple of years previously – also appear in the dance party at the end of the film.

In addition to Poitier’s involvement, the film shows some other signs of being addressed to a US audience. At the very start, Thackeray’s bus journey to Wapping implausibly takes him past a series of holiday-postcard London landmarks (Big Ben, Tower Bridge): presumably the East End location would have been unfamiliar and unexpected to most US viewers. Meanwhile, the film also features the pop singer Lulu playing a fairly prominent role as one of the students, ‘Babs’ Pegg, and singing the sickly title song (which later topped the US charts) no fewer than three times; while the second-division British group The Mindbenders – who had reached number one, and toured America, a couple of years previously – also appear in the dance party at the end of the film.

The film is also updated, from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s. This is evident not just in the vaguely ‘mod’ fashions and hairstyles of the students, and the music they dance to at lunchtimes, but also in some more explicit observations about the ‘sixties generation’. When Thackeray engages his class in a discussion about ‘rebellion’, he mentions the Beatles, observing that ‘every new fashion is a form of rebellion’ – although significantly, he insists that this should be done individually rather than collectively:

It’s your duty to change the world, peacefully – not by violence. Individually – not as a mob.

Meanwhile, Pamela responds to concerns that she might be staying out too late at night and getting into (sexual) trouble with an implied reference to birth control:

We’re the luckiest bunch of kids, the luckiest generation that’s ever been, aren’t we? We’re the first to be really free to enjoy life if we want to – without fear.

On the other hand, this displacement in time raises some questions about the film’s authenticity. London’s docklands were a very different place in the mid-1960s from what they had been a decade earlier. A programme of relocation began in 1965, and the docks were eventually closed to shipping in 1969. The white communities in the area felt increasingly threatened and embattled, and growing racism was one response to this. Mosley’s fascist Blackshirts had been active in the area since the 1930s, and in 1968 the dockers marched in support of the racist politician Enoch Powell following his notorious ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. Of course, the film is not intended as a gritty documentary; and such absences would almost certainly not have been noticed, especially by US audiences.

On the other hand, this displacement in time raises some questions about the film’s authenticity. London’s docklands were a very different place in the mid-1960s from what they had been a decade earlier. A programme of relocation began in 1965, and the docks were eventually closed to shipping in 1969. The white communities in the area felt increasingly threatened and embattled, and growing racism was one response to this. Mosley’s fascist Blackshirts had been active in the area since the 1930s, and in 1968 the dockers marched in support of the racist politician Enoch Powell following his notorious ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. Of course, the film is not intended as a gritty documentary; and such absences would almost certainly not have been noticed, especially by US audiences.

Even so, there are some other differences between the book and the film that have ambivalent consequences for its representation of ‘race’ and racism. In the film, the class is slightly more multicultural than in the book, but (aside from the dual-heritage character of Seales) there are only two token non-white characters, who have non-speaking roles. Once again, this is very different from the reality of the East End in the mid-1960s.

As in the book, some of the teachers and students do give voice to racial prejudice, but this is mostly on the part of ‘bad’ characters like the cynical teacher Mr. Weston and the leather-jacketed delinquent Denham. What is effectively missing is the dimension of structural racism, and the ‘genteel racism’ I referred to above. Thus, Thackeray is clearly attempting to get a job in his chosen profession of engineering: we see him posting several letters of application, and he eventually succeeds in getting an offer by the end of the film (which does not happen in the book). However, it is by no means clear that his failure to find employment is due to racism: the backstory of Braithwaite’s experience on being demobbed from the RAF – and his wider criticisms of British racism – are entirely absent, as are his difficulties in finding accommodation. In one classroom scene, Thackeray presents himself to the students as having held a variety of low-paying, menial jobs (which was not the case for Ricky in the book), and briefly offers them an approximation of his youthful patois, much to their amusement. Yet here again, he promotes an individualistic view that seems close to the American Dream:

As in the book, some of the teachers and students do give voice to racial prejudice, but this is mostly on the part of ‘bad’ characters like the cynical teacher Mr. Weston and the leather-jacketed delinquent Denham. What is effectively missing is the dimension of structural racism, and the ‘genteel racism’ I referred to above. Thus, Thackeray is clearly attempting to get a job in his chosen profession of engineering: we see him posting several letters of application, and he eventually succeeds in getting an offer by the end of the film (which does not happen in the book). However, it is by no means clear that his failure to find employment is due to racism: the backstory of Braithwaite’s experience on being demobbed from the RAF – and his wider criticisms of British racism – are entirely absent, as are his difficulties in finding accommodation. In one classroom scene, Thackeray presents himself to the students as having held a variety of low-paying, menial jobs (which was not the case for Ricky in the book), and briefly offers them an approximation of his youthful patois, much to their amusement. Yet here again, he promotes an individualistic view that seems close to the American Dream:

If you’re prepared to work hard, you can do almost anything. You can get any job you want, you can even change your speech if you want to.

To say the least, this was not Braithwaite’s experience, or that of his narrator Ricky. By contrast in the film, Mark actively chooses (at the very end) not to pursue the offer of a career as an engineer, rather than being prevented from doing so.

Equally significant – and the likely cause of Braithwaite’s own consternation – is the absence of the inter-racial romantic storyline. We do see Gillian (played by Suzy Kendall) casting occasional longing looks in Thackeray’s direction, but their relationship is not developed, as it is in several of the later chapters of the book. (This element was apparently included in Clavell’s early drafts of the script, but subsequently omitted.)

On the other hand, there are two added scenes with the dual-heritage character Seales (played by Anthony Villaroel). In one of these, Thackeray is leaving school one day and encounters Seales hanging about disconsolately in the playground. His enquiry prompts an outburst by Seales, as he kicks away an empty can, that is quite notable for its vehemence:

On the other hand, there are two added scenes with the dual-heritage character Seales (played by Anthony Villaroel). In one of these, Thackeray is leaving school one day and encounters Seales hanging about disconsolately in the playground. His enquiry prompts an outburst by Seales, as he kicks away an empty can, that is quite notable for its vehemence:

I hate him! I hate him! … Never forgive him for what he did to my mum. Never! He married her, didn’t he? Didn’t he?

Mark Christian, writing from a Black British perspective, regards this very critically. Seales, he argues, is shown as ‘psychologically maladjusted’, consumed by ‘pathological hatred’, not just of his black father, but also of his own racial identity. Christian argues that Seales’s character is ‘mauled’ (although in fact he occupies a somewhat smaller part in the book); and that this reflects the white director James Clavell’s negative view of racial integration.[23] There is some truth in this criticism, although it makes a great deal of scenes that are left very much unresolved.

Obviously, a film adaptation is bound to contain less in the way of narrative content – and indeed authorial voice – than the original book; but these are nevertheless very significant omissions and additions, which reflect the film’s problematic approach to the issue of ‘race’ and racism. They also reinforce the generally individualistic and ‘quietist’ approach to racial politics, for which the book was (fairly or unfairly) condemned at the time, and for which Poitier himself had become almost notorious.

A slight return

Almost thirty years after the first film, Poitier reprised his role as Mark Thackeray in the made-for-TV movie To Sir With Love 2, directed (somewhat implausibly) by the legendary Michael Bogdanovich, and screened on CBS in America. E.R. Braithwaite’s views are not on record, but it’s hard to imagine he would have loathed this film any less than he did the first one. Sadly for all concerned, it is an embarrassingly condescending, sentimental piece of work.

The film begins at Mark Thackeray’s retirement party at his old school in London: there are glimpses of the London landmarks once again, and then some brief appearances by Judy Geeson (who played Pamela in the original film) and Lulu, who serenades him once again with the title song. However, the action then shifts to the South Side of Chicago, where Thackeray (now a distinguished and well-known educator) volunteers to take on a substitute teaching role in a tough multicultural school run by an old friend – apparently resisting the temptations of positions at Yale and the University of Chicago. The school is covered with graffiti, there is drug dealing in the yard, and gang violence on the streets: once they are through the security gates, the students fight and smoke in the corridors, and are generally rude and insubordinate. ‘You’ve heard of the blackboard jungle?’ one teacher asks him. ‘This is the swamp.’ Against the advice of the principal, Thackeray chooses to work with the ‘H’ (for ‘horror’) class of ‘no-gooders’, and has to confront disciplinary challenges that are very similar to those he faced at his school in London – as indeed are the various pedagogical solutions he adopts.

The film begins at Mark Thackeray’s retirement party at his old school in London: there are glimpses of the London landmarks once again, and then some brief appearances by Judy Geeson (who played Pamela in the original film) and Lulu, who serenades him once again with the title song. However, the action then shifts to the South Side of Chicago, where Thackeray (now a distinguished and well-known educator) volunteers to take on a substitute teaching role in a tough multicultural school run by an old friend – apparently resisting the temptations of positions at Yale and the University of Chicago. The school is covered with graffiti, there is drug dealing in the yard, and gang violence on the streets: once they are through the security gates, the students fight and smoke in the corridors, and are generally rude and insubordinate. ‘You’ve heard of the blackboard jungle?’ one teacher asks him. ‘This is the swamp.’ Against the advice of the principal, Thackeray chooses to work with the ‘H’ (for ‘horror’) class of ‘no-gooders’, and has to confront disciplinary challenges that are very similar to those he faced at his school in London – as indeed are the various pedagogical solutions he adopts.

The narrative of the second movie is somewhat more individualised in its approach than the first. There are scenes of classroom teaching – most notably, Thackeray teaches (or rather preaches) the wisdom of non-violent resistance, explaining the achievements of Dr. Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. As in the first film, he also insists on politeness (’Sir’ and ‘Miss’, ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ – ‘those magical words’) and takes the students out onto the streets for a field trip, in which they learn to approach strangers with appropriate courtesy. He also moves away from the established curriculum, replacing it with moral homilies about character, determination, dignity and self-respect.

However, the bulk of the film follows Thackeray’s successful efforts to solve the problems of his students: faced with a girl who has been abandoned by her drug-addicted mother, he finds her a room-mate and a part-time job at a newspaper; he intervenes to prevent a girl student from being pimped by her gang-member ‘boyfriend’; he arranges for a misfit (probably gay) student to get a job at a florist shop; and (at greater length) he rescues one of the more delinquent students from being killed by a criminal gang (in the course of which Thackeray is briefly suspended by the school principal). One by one, almost mechanically, each of them is saved. Our hero  also has a personal storyline of his own: now a widower, he has come to Chicago partly in the hope of finding a lost love (who is black). When he eventually finds her, she is on a hospital bed dying, but he also discovers that she has borne his son, whom he now meets for the first time. Like its predecessor, the film ends with a celebratory end-of-year party, and Thackeray announces that he will not be leaving to return to London, but remaining to teach the following year’s students.

also has a personal storyline of his own: now a widower, he has come to Chicago partly in the hope of finding a lost love (who is black). When he eventually finds her, she is on a hospital bed dying, but he also discovers that she has borne his son, whom he now meets for the first time. Like its predecessor, the film ends with a celebratory end-of-year party, and Thackeray announces that he will not be leaving to return to London, but remaining to teach the following year’s students.

As a representation of education, this film is even more sugar-coated than the first. As Poitier’s biographer puts it, ‘if the original’s transformation is hard to swallow, then the sequel’s is completely implausible’.[24] The film offers a caricature of a later-twentieth-century, multicultural urban school – albeit one that is no less schematic, exaggerated and tokenistic than many others on offer at the time (John M. Smith’s film Dangerous Minds, released the previous year, would be one notable example). Clichés and stereotypes come thick and fast. It also replays some of the more problematic aspects of Poitier’s screen persona. Any sexual or romantic involvement is safely in the past (and notably there is no suggestion of miscegenation, since both his former wife and his lost love are black); and the liberal individualism of its politics is much more explicit. Mark Thackeray elevates himself as a kind of moral exemplar; and his extraordinary skills and achievements are effusively praised by all. Mark, it appears, knows everything, and is capable of solving every problem: but he is also insufferably smug.

Conclusion

Despite the title of this essay, I would not wish to interpret these successive versions of To Sir With Love as in any way representative of broader historical changes, either in education itself or in issues to do with ‘race’ and racism. Equally, it is important not to elide the writer E.R. Braithwaite with his narrator Ricky, or with the screen heroes named Mark Thackeray and the actor Sidney Poitier who plays them: the differences between them are important, although of course they partly derive from the different constraints and possibilities of different cultural forms, and different production contexts.

Nevertheless, as I hope I have shown, these different versions of the story are symptomatic of broader public debates about these issues over the years – as indeed are the critical responses they have provoked. As I’ve argued, To Sir With Love has a good deal in common with a broader range of other representations, especially in the cinema. The continuing popularity of the story across several decades[25] would suggest that it speaks to wider public perceptions, both of education and of ‘race relations’, in ways that hold an enduring emotional appeal.

NOTES

[1] Information on Braithwaite’s life was obtained from several sources, including Wikipedia, a British Library webpage (Wambu, 2011), an obituary in the Guardian newspaper (Mair, 2016), Braithwaite’s preface to a collection of ‘Windrush generation’ writing (Braithwaite, 1998), an essay on the London Fictions site (Thomas, 2013) and an introduction to the novel’s Vintage edition (Philips, 2005).

[2] Braithwaite (1998).

[3] See Wambu (2011), Vaade (2015), McLeod (2013) and Ferrebe (2012); and for examples of such work, Wambu (1998)

[4] See Thomas (op. cit.). Stuart Hall’s (1961) review of this and other books regards them as reflections of the difficulties of teaching the ‘secondary modern generation’ – working-class students confined to the lower tier of a hierarchical education system.

[5] There have been numerous academic accounts of this issue, especially in relation to cinema. For this essay, I have found the studies by Ellsmore (2005) and Leopard (2007) particularly useful.

[6] I have discussed Blackboard Jungle elsewhere: Buckingham (2017).

[7] Leopard, op. cit.

[8] This is quite evident in Stuart Hall’s review essay: Hall, op. cit.

[9] See Weber and Mitchell (1995).

[10] See Ellsmore, op. cit. Thomas (op. cit.) suggests that the reality of Braithwaite’s own classroom may have been rather different from the way it is represented in the book.

[11] I have discussed MacInnes’s work in another essay on this site: Buckingham (2016).

[12] Page references throughout are to the Vintage edition (2005).

[13] There are many similarities between this dismal view of working-class youth and the contemporary observations of Richard Hoggart (1958) and Stuart Hall (op. cit), although the latter is rather less pessimistic.

[14] Perhaps the most curious aspect of this for the contemporary reader is Ricky’s apparent fascination with women’s breasts: on the very first page, he comments on the ‘huge-breasted’ and ‘bovine’ women he sees on the bus, and most of the female teachers are introduced with some commentary on the size or shape of their breasts. More disturbingly, the same is true of several of the female students: one, Jane Purcell, is endowed with ‘heavy breasts which swung loosely under a thin jumper, evidently innocent of any support’ (49), and later becomes the focus of staffroom discussion, in which she is referred to as ‘Droopy’. In the final scene, Pamela, the student with the crush, is described in similarly lubricious terms.

[15] Birbalsingh’s criticisms have a rather obnoxious ad hominem tone. From what I have been able to discover, his own experience had been remarkably similar to Braithwaite’s: he too was from Guyana, and worked as a substitute teacher in London in the early 1960s. To add to the intrigue, Birbalsingh’s daughter is none other than Britain’s leading right-wing culture warrior on education, Katharine Birbalsingh, who cultivates a reputation as ‘Britain’s strictest headteacher’ (see Buckingham (2020) for an analysis of her racial politics). Even more curiously, she is the author of a novel/memoir about her teaching experiences entitled To Miss With Love (2011), which features a student called ‘Braithwaite’. There is probably an interesting story to be told here about the relations between the personal and the political…

[16] McLeod, op. cit.

[17] Or, as he later put it, the British ‘reverted to type, demonstrating the same racism they had so roundly condemned in the Germans’ (Braithwaite, 1998).

[18] Information in this section comes from the usual online sources, but primarily from the biography by Goudsouzian (2004).

[19] Poitier was actually born in the Bahamas, and hence an immigrant to the United States. Strictly speaking, he was not ‘African-American’, even if he was perceived as such.

[20] Quotations here all come from Goudsouzian, op. cit.

[21] Again, all quotations are from Goudsouzian, op. cit.

[22] This quotation comes from a currently unavailable BBC radio profile, as reported by Thomas, op. cit.

[23] Quotations here are from Christian (2015). See also Manolachi (n.d.) for a more positive (and in my view, rather questionable) interpretation.

[24] Goudsouzian, op. cit., 372.

[25] There have been at least two further adaptations, for radio and the stage, since the second film: see Manolachi, op. cit.

___________________________________________

REFERENCES

Birbalsingh, F.M. (1968) ‘To John Bull, with hate’, Caribbean Quarterly 14(4): 74-81

Birbalsingh, Katharine (2011) To Miss With Love Harmondsworth: Penguin

Braithwaite, E.R. (1959/2005) To Sir With Love London: Vintage

Braithwaite, E.R. (1967) ‘The “colored immigrant” in Britain’, Daedalus 96(2): 496-511

Braithwaite, E.R. (1998) ‘Preface’, in Onyekachi Wambu (ed.) Empire Windrush: 50 Years of Writing about Black Britain London: Gollancz

Buckingham, David (2016) ‘Before London started swinging: representing the British beatniks’, https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/before-london-started-swinging-representing-the-british-beatniks/

Buckingham, David (2017) ‘Troubling teenagers: how movies constructed the juvenile delinquent in the 1950s’, https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/troubling-teenagers-how-movies-constructed-the-juvenile-delinquent-in-the-1950s/

Buckingham, David (2020) ‘The curriculum of Brexit: culture, education and power the Michaela way’, https://davidbuckingham.net/2020/12/12/the-curriculum-of-brexit-culture-education-and-power-the-michaela-way/

Christian, Mark (2015) ‘To Sir With Love: a Black British perspective’, in Ian Gregory Strachan and Mia Mask (eds.) Poitier Revisited: Reconsidering a Black Icon in the Obama Age London; Bloomsbury

Ellsmore, Susan (2005) Carry on Teachers! Representations of the Teaching Profession in Screen Culture Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham

Ferrebe, Alice (2012) Literature of the 1950s: Good, Brave Causes Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Goudsouzian, Aram (2004) Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press

Hall, Stuart (1959) ‘Absolute beginnings: reflections on the secondary modern generation’, Universities and Left Review 7: 17-25

Hoggart, Richard (1958) The Uses of Literacy Harmondsworth: Penguin

Leopard, Dan (2007) ‘Blackboard Jungle: the ethnographic narratives of education on film’, Cinema Journal 46(4): 22-44

Mair, John (2016) ‘E.R. Braithwaite Obituary’ Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/dec/14/er-braithwaite-obituary

Manolachi, Monica (n.d.) ‘Ethnic, racial and gender sensibilities in To Sir With Love’, on academia.edu (no further details available)

McLeod, John (2012) ‘Lessons from London: E.R. Braithwaite and black writing in 1950s Britain’, Yearbook of English Studies 42: 64-78

Phillips, Caryl (2005) ‘Introduction’ in E.R. Braithwaite To Sir With Love London: Vintage

Thomas, Susie (2013) ‘E.R. Braithwaite: To Sir With Love’, London Fictions: https://www.londonfictions.com/er-braithwaite-to-sir-with-love.html

Vaade, Aarthe (2015) ‘Narratives of migration, immigration and interconnection’, in James, David (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to British Fiction Since 1945 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Wambu, Onyekachi (ed.) (1998) Empire Windrush: 50 Years of Writing about Black Britain London: Gollancz

Wambu, Onyekachi (2011) ‘Black British literature since Windrush’, British Library: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/modern/literature_01.shtml

Weber, Sandra and Mitchell, Claudia (1995) That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Like a Teacher: Interrogating Images and Identity in Popular Culture London: Routledge