By the summer of 1958, London’s popular music scene had reached a crossroads. The trend for skiffle was now more or less exhausted. Its leading proponent, Lonnie Donegan, was moving off into mainstream showbiz; and the vast numbers of amateur and semi-professional bands that followed in his wake had largely disappeared. Two of Donegan’s original bandmates in the Chris Barber band, the guitarist Alexis Korner and the harmonica-player and singer Cyril Davies, had tired of skiffle; and in July of that year, they rebranded their weekly club night above the Roundhouse pub in Soho from skiffle to blues, as the London Blues and Barrelhouse Club. It was a risky move: the initial audience for the new club was reportedly just three people. But by the end of the year, the venue was starting to fill up once more…

By the summer of 1958, London’s popular music scene had reached a crossroads. The trend for skiffle was now more or less exhausted. Its leading proponent, Lonnie Donegan, was moving off into mainstream showbiz; and the vast numbers of amateur and semi-professional bands that followed in his wake had largely disappeared. Two of Donegan’s original bandmates in the Chris Barber band, the guitarist Alexis Korner and the harmonica-player and singer Cyril Davies, had tired of skiffle; and in July of that year, they rebranded their weekly club night above the Roundhouse pub in Soho from skiffle to blues, as the London Blues and Barrelhouse Club. It was a risky move: the initial audience for the new club was reportedly just three people. But by the end of the year, the venue was starting to fill up once more…

The years between 1959 and 1963 were a defining period in the history of British popular music, whose ramifications were felt throughout the decade that followed.[1] Korner and Davies eventually had to leave the Roundhouse after they moved away from acoustic ‘country’ blues towards a more urban style, using electric guitars. In March 1962, now playing (and recording) as ‘Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated’, they opened a new club venue in the West London suburb of Ealing, which quickly became one of the most important breeding grounds for the first British rhythm and blues boom. The eager young men who clamoured to join Korner’s band on stage included many now-legendary names in the history of rock: this was where the Rolling Stones came together, and where performers like Eric Clapton, Paul Jones, Eric Burdon, Pete Townshend and Long John Baldry began their careers. By the end of 1963, it has been estimated that around 140 rhythm and blues groups were performing regularly in the Greater London area alone, with a total of 300 in the UK as a whole; and following the success of a new generation of bands, including the Stones, the Animals, Manfred Mann and the Yardbirds, this had grown to as many as 2000 by the end of 1964.[2] What had begun as a somewhat cultish minority enthusiasm had rapidly become a mass market phenomenon.

In this essay, I want to explore why this ‘boom’ appeared at this time, and in this location. In the process, I will be addressing broader questions about the emerging social changes of the period, as well as more specific issues to do with the transatlantic trade in culture, and with ‘race’ and authenticity. In doing so, I want to resist the tendency towards romantic mythology that is so pervasive in histories of popular music.[3] It might have been tempting to explore this period by focusing on some of the younger (and now much better-known) musicians who first appeared at this time, like Mick Jagger or Eric Clapton. Yet rather than re-telling stories that have been told a thousand times before, I want to focus on Alexis Korner, a man frequently described as the ‘father’ of British rhythm and blues – a title he reportedly loathed.[4] Korner’s career straddles the period that is my central focus here. What makes him interesting is not so much his music itself as his role as a catalyst for the wider scene: he was a mentor and patron for younger musicians, an impresario and an entrepreneur, and a public commentator and proselytiser for the music – or what we might call today a cultural intermediary.

In this essay, I want to explore why this ‘boom’ appeared at this time, and in this location. In the process, I will be addressing broader questions about the emerging social changes of the period, as well as more specific issues to do with the transatlantic trade in culture, and with ‘race’ and authenticity. In doing so, I want to resist the tendency towards romantic mythology that is so pervasive in histories of popular music.[3] It might have been tempting to explore this period by focusing on some of the younger (and now much better-known) musicians who first appeared at this time, like Mick Jagger or Eric Clapton. Yet rather than re-telling stories that have been told a thousand times before, I want to focus on Alexis Korner, a man frequently described as the ‘father’ of British rhythm and blues – a title he reportedly loathed.[4] Korner’s career straddles the period that is my central focus here. What makes him interesting is not so much his music itself as his role as a catalyst for the wider scene: he was a mentor and patron for younger musicians, an impresario and an entrepreneur, and a public commentator and proselytiser for the music – or what we might call today a cultural intermediary.

A British bluesman?

Alexis Korner was born in Paris in 1928, although his family was already based in London at the time.[5] His father was an Austrian Jew; his mother was Greek, although she had lived in Istanbul. Both worked across Europe and beyond in the international shipping business. Alexis spent some of his early years at schools in France and Switzerland, but he mostly attended elite private schools in London. His childhood was somewhat unsettled, not to say neglected; as a teenager, he began to engage in petty thieving, and was eventually sent to a therapeutic residential school for troubled adolescents.

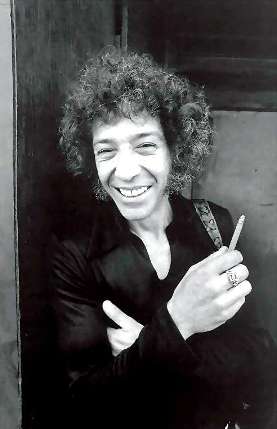

As this would suggest, Korner’s upbringing was not exactly typical of the impoverished Mississippi Delta ‘bluesman’ of popular legend. He came from an affluent cosmopolitan family, and spoke several languages. While he later saw himself as ‘breaking down the British three-class system’,[6] and was never wealthy in his own right, his background was undoubtedly privileged. Racially, he was quite ambiguous: with olive skin, he was apparently regarded as ‘not English’ by other children at school. By the mid-1950s, with his long hair and bohemian dress, and his penchant for liquorice-paper roll-ups, Korner came across as somewhat bewilderingly exotic. At the peak of his career, he sported a large Afro hairstyle with Victorian mutton-chop sideburns, and often a leather hat; yet his urbane upper-class English accent (and his husky, sumptuous voice) was undoubtedly key to his later success as a radio presenter.

As this would suggest, Korner’s upbringing was not exactly typical of the impoverished Mississippi Delta ‘bluesman’ of popular legend. He came from an affluent cosmopolitan family, and spoke several languages. While he later saw himself as ‘breaking down the British three-class system’,[6] and was never wealthy in his own right, his background was undoubtedly privileged. Racially, he was quite ambiguous: with olive skin, he was apparently regarded as ‘not English’ by other children at school. By the mid-1950s, with his long hair and bohemian dress, and his penchant for liquorice-paper roll-ups, Korner came across as somewhat bewilderingly exotic. At the peak of his career, he sported a large Afro hairstyle with Victorian mutton-chop sideburns, and often a leather hat; yet his urbane upper-class English accent (and his husky, sumptuous voice) was undoubtedly key to his later success as a radio presenter.

After an unsuccessful period as a clerk in the family business and a stint in the army (where he worked in the record library of the British Forces Network), Korner began to forge a career in music, alongside a day job as a studio manager for the BBC World Service. Inspired initially by the boogie-woogie piano of Jimmy Yancey and then by ‘country’ blues musicians like Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy, he was self-taught, and remained somewhat unconfident of his musical abilities for many years. By the mid-1950s, he was playing acoustic guitar and mandolin in Chris Barber’s traditional jazz band, where he was also part of a spin-off group playing skiffle (a hybrid of blues, country-and-western and early rock-and-roll, using some home-made instruments) in the intermissions at gigs. His earliest recordings, which will be discussed later, were very much in this genre, although his musical interests started to change as US musicians like Muddy Waters and Sister Rosetta Tharpe began appearing in the UK playing electric instruments.

After the demise of skiffle, Korner continued to perform (sometimes solo, or in a duo) in London clubs, mostly playing blues, but with a foot in the emerging folk and traditional jazz scenes. In addition to setting up and programming new clubs and venues, his activities as an ‘intermediary’ during this period were quite diverse. Although he had resigned from his role at the BBC in 1957, he continued to appear in (and eventually present) radio programmes. He wrote for the national music press, most notably the Melody Maker; was briefly an A+R man for record labels; and curated and wrote sleeve notes for archival recordings (the RCA series Alexis Korner Presents the Kings of the Blues was one early 1960s venture). He also hosted visiting African-American musicians, giving some of them their first experience of staying in a white household.

Korner’s fully electric group Blues Incorporated was formed in late 1961. Cyril Davies, a long-term musical partner since the mid-1950s, played a front line role as a harmonica player and singer; although he was a very different personality from Korner, and eventually left the band in late 1962 (he died early in 1964). The band had a shifting personnel, which included some noted modern jazz musicians, as well as future members of Cream; and as the ‘boom’ took off, it pursued a gruelling, drug- and drink-fuelled live performance schedule. Recordings, to be considered later in this essay, were limited, as indeed were financial rewards, and amid ‘musical differences’ the band eventually folded in 1965.

Korner’s fully electric group Blues Incorporated was formed in late 1961. Cyril Davies, a long-term musical partner since the mid-1950s, played a front line role as a harmonica player and singer; although he was a very different personality from Korner, and eventually left the band in late 1962 (he died early in 1964). The band had a shifting personnel, which included some noted modern jazz musicians, as well as future members of Cream; and as the ‘boom’ took off, it pursued a gruelling, drug- and drink-fuelled live performance schedule. Recordings, to be considered later in this essay, were limited, as indeed were financial rewards, and amid ‘musical differences’ the band eventually folded in 1965.

After this time, Korner’s career was more diverse and uneven. He was rather left behind by what some call the second rhythm and blues boom of the later 1960s, and seems to have resented the success of some of the younger musicians who came up in his wake. In the mid-1960s, he even took on an implausible role as the musical director of a popular children’s television show, Five O’Clock Club. By this point, he appeared to be more interested in playing jazz, or at least jazz-rock; although he had a career renaissance of sorts at the start of the 1970s with the short-lived commercial success of CCS, a pop-oriented big band. Other bands and international tours followed, but by the 1970s, he was mostly known as a radio presenter, while also working as a voice-over artist. Korner died quite suddenly from lung cancer on New Year’s Day 1984.

Why now, why here?

Why did this musical boom happen when it did, and what does it tell us about the broader social changes of the period? Popular accounts tend to present it as a kind of revolution, or at least a ‘controlled revolt’, that was led by young people.[7] As one decade gave way to the next, young people gradually took over the reins, forging new modes of creative expression and blowing away the moral and cultural conservatism of the fifties. Popular music – and particularly music of African-American origin – was a crucial resource in this rebellion against conformity. Or so the story goes.

Instances of this story are easy to find. Perhaps the most entertaining is Pete Frame’s book The Restless Generation, which has great fun mocking adults’ misunderstanding and rejection of the newly emerging forms of pop and rock-and-roll in the latter half of the fifties.[8] Likewise, the BBC documentary How Britain Got the Blues presents the early 1950s as a period of grey austerity, which offered ‘nothing for young people’. The advent of rock-and-roll meant that young people now had a distinctive form of music that was different from that of their parents; although the adults who owned Tin Pan Alley (or its British equivalent) did their best to claw back control with a tide of bland, superficial crooners.[9] According to such accounts, the rhythm and blues boom was a kind of generational revenge, especially on the part of working-class youth: in addition to the promise of sex, drink and drugs, it represented a new kind of energy and aggression that challenged the consensus of 1950s Britain – as well as the artificiality of commercially manufactured pop.

Instances of this story are easy to find. Perhaps the most entertaining is Pete Frame’s book The Restless Generation, which has great fun mocking adults’ misunderstanding and rejection of the newly emerging forms of pop and rock-and-roll in the latter half of the fifties.[8] Likewise, the BBC documentary How Britain Got the Blues presents the early 1950s as a period of grey austerity, which offered ‘nothing for young people’. The advent of rock-and-roll meant that young people now had a distinctive form of music that was different from that of their parents; although the adults who owned Tin Pan Alley (or its British equivalent) did their best to claw back control with a tide of bland, superficial crooners.[9] According to such accounts, the rhythm and blues boom was a kind of generational revenge, especially on the part of working-class youth: in addition to the promise of sex, drink and drugs, it represented a new kind of energy and aggression that challenged the consensus of 1950s Britain – as well as the artificiality of commercially manufactured pop.

Of course, there is some truth in this story. For obvious reasons, the after-effects of war lasted much longer in the UK than they did in the United States: food rationing continued until 1954, and National Service did not end until 1960. As Lynda Nead has described, the emotional ‘atmosphere’ – or the ‘structure of feeling’ – of the decade following the war was predominantly grey and melancholy: many cities were littered with bombsites, and reconstruction was slow to proceed.[10] While the emerging forms of youthful consumption identified by the market researcher Mark Abrams were certainly becoming apparent by the end of the decade, they were perhaps not quite as widespread as he suggested (see here). Although this was a period of almost full employment, some less affluent young people were undoubtedly ‘left behind’; and it is possible that some of the more assertive, even abrasive, forms of music that were starting to be imported from the United States offered some of them a vehicle for their frustrations…[11]

However, there are many risks in these kinds of explanations. Historically, popular music – and the activities associated with it – have often been regarded as an expression of resistance to authority; and in turn, legal and critical authorities have frequently sought to control it. Youth is certainly one dimension of this, and (as I’ll discuss in more detail later), so is ‘race’: the troubling enthusiasm of young white British audiences for African-American music can be traced back from the early days of jazz right through to contemporary variants of hip-hop.[12] In this respect, the short-lived skiffle phenomenon of the mid-1950s, and the more lasting rhythm and blues boom that followed it, were far from new, even if they were much larger in scale than what had preceded them.

Yet this was not exclusively a matter for youth: there was a significant intergenerational dimension here. Alexis Korner was fourteen years younger than Colin MacInnes, but he was still quite a lot older than most of the younger musicians he brought under his wing. By the boom years of 1962-3, he was thirty-five – as compared, for example, with proteges like Mick Jagger, Brian Jones and Keith Richards, who were only just emerging from their teens. His biographer Harry Shapiro presents Korner’s own teenage experiences in terms of ‘juvenile delinquency’, although this rather overstates the case: he was certainly expelled from school, but he was not exactly a member of a criminal gang.[13] Furthermore, as I’ve emphasised, his background was privileged, even if it was far from conventionally British middle-class. This much was also true of many of the younger performers whom he mentored at the Ealing Club: Jagger was a student at the London School of Economics, while Paul Jones (later of Manfred Mann) had just dropped out of Oxford. Many of the key participants in the R&B boom were by no means proletarian.

Yet this was not exclusively a matter for youth: there was a significant intergenerational dimension here. Alexis Korner was fourteen years younger than Colin MacInnes, but he was still quite a lot older than most of the younger musicians he brought under his wing. By the boom years of 1962-3, he was thirty-five – as compared, for example, with proteges like Mick Jagger, Brian Jones and Keith Richards, who were only just emerging from their teens. His biographer Harry Shapiro presents Korner’s own teenage experiences in terms of ‘juvenile delinquency’, although this rather overstates the case: he was certainly expelled from school, but he was not exactly a member of a criminal gang.[13] Furthermore, as I’ve emphasised, his background was privileged, even if it was far from conventionally British middle-class. This much was also true of many of the younger performers whom he mentored at the Ealing Club: Jagger was a student at the London School of Economics, while Paul Jones (later of Manfred Mann) had just dropped out of Oxford. Many of the key participants in the R&B boom were by no means proletarian.

It’s also important to note that this was a predominantly masculine phenomenon. Previous histories have tended to marginalise female performers, both visiting Americans like Sister Rosetta Tharp and British blues singers like Beryl Bryden (who recorded with Korner, as we’ll see) and Ottilie Patterson.[14] However, Bryden and Patterson performed mainly in the context of traditional jazz – a style from which rhythm and blues bands were keen to distance themselves by the early 1960s. In all the contemporary accounts and recollections of the R&B ‘boom’ I have read, there is scarcely any evidence of female performers: young women were perceived almost exclusively as fans, who might prove sexually ‘available’ to fortunate male musicians – although unlike ‘Beatlemania’, fandom here was far from comprehensively dominated by girls and young women.[15] Meanwhile, the romantic image of the itinerant ‘Negro bluesman’ arguably provided a fantasy of black hyper-masculinity that had a particular appeal to white males barely emerging from adolescence.[16]

Subcultures and scenes

Early sociological studies of youth culture tended to see it in terms of subcultures; and there certainly were subcultural dimensions to early rhythm and blues in Britain. Although they congregated at venues like the Ealing Club, the participants – fans as well as musicians – came from quite dispersed locations; and some of them initially felt themselves to be isolated members of a kind of secret society. Brian Jones, for example, claimed that he was ‘the only kid in Cheltenham listening to Elmore James’; while Tom McGuinness (later of Manfred Mann) said ‘we felt we were part of some obscure cult or sect’.[17] Again, this wasn’t entirely new: in the 1930s, some early followers of jazz in Britain had gathered in ‘rhythm clubs’ to listen to recordings of American artists, and regarded their rare and treasured 78s almost as fetishes.[18]

More recently, however, many researchers have challenged the concept of subcultures, and some have sought to replace it with a focus on youth cultural ‘scenes’.[19] This approach regards youth culture (and young people’s use of popular music) as a matter of shifting and temporary relationships, rather than the ‘card-carrying’ membership implied by the notion of subculture. The emphasis here is on how performers and fans tend to cluster together in particular geographical locations: there are local scenes that develop in a particular region, city or neighbourhood, although there is also some attention to the relation between the local and the global, especially in the form of the international music industry.

This approach can be usefully applied to the nascent British rhythm and blues scene. The wider global context here is obviously to do with Britain’s complex and ambivalent relationship with its former colony, the United States – a relationship that became more fraught as Britain gradually recognised its declining status as an imperial world power. That relationship is self-evidently economic and political, and it depends upon a shared language; but it has always been mediated through the transatlantic trade in culture. While some commentators have sought to play down or deprecate American influence, US popular culture has frequently offered a source of refreshing, and sometimes rebellious, ideas and images that have proven particularly attractive to younger audiences.[20] What appealed to many young people in the 1950s and early 1960s was also a rather different version of America: as Dave Harker puts it, the interest was not so much in the America of ‘big business, Hollywood, comic books and cultural imperialism’, but of ‘Joe Hill, Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie and the cultural resourcefulness of the regular working man’.[21]

However, this inward flow of cultural influences was far from straightforward. From the mid-1930s until the late 1950s, the British Musicians’ Union operated an effective ban on visiting overseas artists, with the significant exception of singers (who could be categorised as ‘entertainers’).[22] While this left British jazz and blues musicians largely reliant on recordings to learn their craft, it may also have added to the music’s subcultural cachet, especially because the recordings were so difficult to obtain – not least because the music that enthusiasts really wanted to hear was ignored and marginalised by the mainstream (white) music industry in the United States itself. Yet despite the growing numbers of British performers, the overriding enthusiasm here was for African-American music by black artists. This music was seen by most – fans, critics, and most performers – as authentic, in ways that the British equivalents could never hope to be; and these claims for authenticity had a strong racial dimension, as we’ll see below. White (British) boys, it was argued, simply couldn’t play the (black, American) blues.

Despite these transatlantic connections, the early British rhythm and blues scene was also quite localised, and surprisingly suburban. It was undeniably centred on London, although bands frequently toured outside the capital, albeit with difficulty, well before the advent of motorways; and specialist clubs eventually opened in several major cities. Yet while Korner and his cohorts played in several famous and infamous locations in the city centre (most notably the Marquee, the Flamingo and the 100 Club), many of the most important venues were in the relatively affluent and sedate suburbs of South West London – which some have ironically called ‘the Thames delta’. Ealing was known at the time as ‘the queen of the suburbs’, although the Ealing Club itself was located in a damp basement underneath the ABC tearoom opposite the tube station. It was pre-dated by the Eel Pie Island club in leafy Twickenham, and soon there were similar clubs in equally affluent locations like Richmond, Sutton, Putney and Windsor.[23] In several cases, the proximity of local art schools, which several of the musicians and fans were attending, was an additional factor:[24] the Ealing Club, for example, was owned by Fery Asgardi, an Iranian who had moved on from being the social secretary of the students’ union at the Ealing Art School.

Despite these transatlantic connections, the early British rhythm and blues scene was also quite localised, and surprisingly suburban. It was undeniably centred on London, although bands frequently toured outside the capital, albeit with difficulty, well before the advent of motorways; and specialist clubs eventually opened in several major cities. Yet while Korner and his cohorts played in several famous and infamous locations in the city centre (most notably the Marquee, the Flamingo and the 100 Club), many of the most important venues were in the relatively affluent and sedate suburbs of South West London – which some have ironically called ‘the Thames delta’. Ealing was known at the time as ‘the queen of the suburbs’, although the Ealing Club itself was located in a damp basement underneath the ABC tearoom opposite the tube station. It was pre-dated by the Eel Pie Island club in leafy Twickenham, and soon there were similar clubs in equally affluent locations like Richmond, Sutton, Putney and Windsor.[23] In several cases, the proximity of local art schools, which several of the musicians and fans were attending, was an additional factor:[24] the Ealing Club, for example, was owned by Fery Asgardi, an Iranian who had moved on from being the social secretary of the students’ union at the Ealing Art School.

While profit-making entrepreneurs (managers, promoters, record labels) gradually moved in, and bands like the Stones and the Yardbirds were quickly lured away to more lucrative central London venues, the infrastructure of these local scenes was initially created by the participants themselves – the venues, rehearsal rooms and meeting places, the specialist record and music shops, and the various forms of media and publicity. In the vicinity of the Ealing Club, for example, bands also played in downmarket venues like the Hanwell Community Centre and the Feathers pub; while just up the road, they would meet and try out instruments in Marshall’s music shop (from whence came the Marshall amplifier, which played a defining role in the electric guitar sound of 1960s rock). In these respects, suburban South West London has a good deal in common with more celebrated popular music scenes like Liverpool and Memphis in the 1960s, or even Olympia in the 1990s or East London in the early 2000s.

While profit-making entrepreneurs (managers, promoters, record labels) gradually moved in, and bands like the Stones and the Yardbirds were quickly lured away to more lucrative central London venues, the infrastructure of these local scenes was initially created by the participants themselves – the venues, rehearsal rooms and meeting places, the specialist record and music shops, and the various forms of media and publicity. In the vicinity of the Ealing Club, for example, bands also played in downmarket venues like the Hanwell Community Centre and the Feathers pub; while just up the road, they would meet and try out instruments in Marshall’s music shop (from whence came the Marshall amplifier, which played a defining role in the electric guitar sound of 1960s rock). In these respects, suburban South West London has a good deal in common with more celebrated popular music scenes like Liverpool and Memphis in the 1960s, or even Olympia in the 1990s or East London in the early 2000s.

Policing authenticity

The geographical distance between the original performers of this music and their followers on the other side of the Atlantic created a dilemma. Before the late 1950s, the restrictions imposed by the Musicians Union meant that hardly any US blues artists had performed in Britain; the music was rarely played on the radio, and recordings were expensive and difficult to obtain. In an industry that was largely governed by commercial imperatives, who could tell whether British audiences were getting the ‘real thing’?

The idea of authenticity – and the values attached to it – can be traced back to nineteenth-century Romanticism: it reflects a much broader critique of the homogenizing effects of industrialisation and mass culture, and the apparent disappearance of rural traditions and ways of life. In Britain, there are elements of this in the early twentieth-century revival of ‘folk’ music, and in the ideas about ‘organic community’ that informed literary critics like F.R. Leavis.[25] However, it was in the 1950s that the concern about authenticity began to dominate the critical debate. According to Tom Hennessy,[26] ‘authenticism’ became a key element of New Left thinking, in response to what was perceived as an ‘Americanised’ consumer culture. Yet as Hennessy and others suggest, authenticity was a shifting and elusive quality.[27] Authentic art needed to be defined in relation to an opposite that was seen as fake and commercialised; yet maintaining such distinctions required constant policing – not least because there were likely to be competing ‘authenticities’ and ‘authenticators’.

This question of authenticity has been an abiding preoccupation in responses to popular music.[28] The policing of fine distinctions is obviously very familiar in musical subcultures, and is a key dimension of what has been called ‘subcultural capital’ – the things that true insiders know, but which are invisible or insignificant for outsiders.[29] While this takes different forms in relation to different musical genres, it frequently rests on a fundamental distinction between mass and minority taste – or between the ‘mainstream’ and the ‘underground’. In this context, anything that might smack of ‘going commercial’ or ‘selling out’ is the ultimate sin. Authenticity is deemed to be fundamentally incompatible with popular success, and ultimately with capitalism itself.

This question of authenticity has been an abiding preoccupation in responses to popular music.[28] The policing of fine distinctions is obviously very familiar in musical subcultures, and is a key dimension of what has been called ‘subcultural capital’ – the things that true insiders know, but which are invisible or insignificant for outsiders.[29] While this takes different forms in relation to different musical genres, it frequently rests on a fundamental distinction between mass and minority taste – or between the ‘mainstream’ and the ‘underground’. In this context, anything that might smack of ‘going commercial’ or ‘selling out’ is the ultimate sin. Authenticity is deemed to be fundamentally incompatible with popular success, and ultimately with capitalism itself.

This is evidently a concern for performers and for audiences; yet critics, record collectors, promoters, record companies and other intermediaries play a key role in defining what counts as the genuine article, and in policing the boundaries between the authentic and the counterfeit. In Britain, this has been a significant issue in the reception of American music in particular. The ‘rhythm clubs’ formed in the 1930s in Britain sought to create a small but informed audience for rare American jazz recordings. More commercial ‘swing’ music, often performed by white musicians, was deemed to be a diluted, artificial version of ‘real’ jazz, which was seen to possess a kind of purity and emotional honesty. The issue of authenticity was equally at stake in the 1950s, in the often bitterly contested arguments between ‘traditionalists’ and ‘revivalists’ in relation to older styles of jazz: the former were more ‘purist’ in their attempts to reproduce the original 1920s New Orleans style, and saw the latter as too populist and eclectic – especially once such music began to achieve commercial success in the ‘trad jazz boom’ of the early 1960s.[30] (Interestingly, such questions were much less evident in responses to modern (post-bebop) jazz.)

In the case of blues, and subsequently rhythm and blues, these issues were equally fraught. As with early jazz, critical lines were drawn between what were seen as ‘folk’ and ‘pop’ versions of blues.[31] From the 1930s onwards, white American critics, archivists and record collectors had been busily gathering and cataloguing examples of what they saw as authentic rural blues; and this also had a transatlantic dimension, not least in the work of the earliest blues scholars like the British writer Paul Oliver.[32] Rather like the ‘folk revival’ of the early twentieth century, this was arguably less a matter of rediscovery than of inventing a tradition that was deemed to be somehow pre-modern and artless, and therefore free of commercial corruption. The defining image was of the Southern ‘bluesman’, an itinerant, dirt-poor cotton picker with an acoustic guitar, epitomised by the popular legend of Robert Johnson.[33] The bluesman was deemed to be speaking the unvarnished truth about suffering and oppression – unlike more popular performers, who had been seduced into becoming mere entertainers for commercial gain. Any hint of artifice or professionalism – let alone of crowd-pleasing – was to be firmly condemned.

In the case of blues, and subsequently rhythm and blues, these issues were equally fraught. As with early jazz, critical lines were drawn between what were seen as ‘folk’ and ‘pop’ versions of blues.[31] From the 1930s onwards, white American critics, archivists and record collectors had been busily gathering and cataloguing examples of what they saw as authentic rural blues; and this also had a transatlantic dimension, not least in the work of the earliest blues scholars like the British writer Paul Oliver.[32] Rather like the ‘folk revival’ of the early twentieth century, this was arguably less a matter of rediscovery than of inventing a tradition that was deemed to be somehow pre-modern and artless, and therefore free of commercial corruption. The defining image was of the Southern ‘bluesman’, an itinerant, dirt-poor cotton picker with an acoustic guitar, epitomised by the popular legend of Robert Johnson.[33] The bluesman was deemed to be speaking the unvarnished truth about suffering and oppression – unlike more popular performers, who had been seduced into becoming mere entertainers for commercial gain. Any hint of artifice or professionalism – let alone of crowd-pleasing – was to be firmly condemned.

Yet in practice, authenticity was not so much an inherent quality of the music itself, but a matter of conforming to preconceived ideas about how music ought to sound. American blues artists, initially surprised by British interest in their work (some at least had retired from performing), eventually learned to adjust to the expectations of British audiences: performers like Big Bill Broonzy (who was a major influence on Korner and his associates) learned to play up to the ‘bluesman’ stereotype. As later critics have suggested, there was an element of ‘minstrelsy’ here – a performance of authenticity that became ‘commercial’ in its own right.[34] A key dividing line was in the use of electric guitars, not just as rhythmic and chordal instruments but also to perform single-note lines in solos. When Muddy Waters first appeared in Britain in 1958, there was some consternation about the fact that he used an electric Telecaster guitar; and when he returned in 1962, he had switched to an acoustic instrument in the hope of giving British audiences more of what they wanted – although unfortunately for him, tastes had moved on in the meanwhile.[35]

The key issue here, as I’ve implied, is that in this context the question of authenticity was explicitly racialised.[36] And while it was one thing for white audiences to enthuse over black blues musicians, it was quite a different matter when white performers began to appear on the scene. The question of whether white boys (and it was mainly boys) could play or sing the blues became a primary focus of critical debate.[37] There may have been aesthetic reasons for these concerns – which I’ll consider in due course – but they were also highly political. Unlike jazz, which had now become semi-respectable, black American blues served a political function in the story of the civil rights movement, which was beginning to be reported in the UK at this time. Arguably, it provided a way for white liberal-minded young people to proclaim a kind of solidarity with an oppressed (but geographically very distant) people. Yet for whites to appropriate such music as performers – and especially to do so thousands of miles away – seemed to some to be at least inauthentic, if not as downright theft. British critics and emergent blues scholars like Paul Oliver viewed ‘white’ blues with abhorrence. White musicians, they argued, lacked the life experience of true bluesmen, and could never hope to match the qualities of ‘soul’ and raw emotional honesty that somehow automatically flowed from that.[38]

The key issue here, as I’ve implied, is that in this context the question of authenticity was explicitly racialised.[36] And while it was one thing for white audiences to enthuse over black blues musicians, it was quite a different matter when white performers began to appear on the scene. The question of whether white boys (and it was mainly boys) could play or sing the blues became a primary focus of critical debate.[37] There may have been aesthetic reasons for these concerns – which I’ll consider in due course – but they were also highly political. Unlike jazz, which had now become semi-respectable, black American blues served a political function in the story of the civil rights movement, which was beginning to be reported in the UK at this time. Arguably, it provided a way for white liberal-minded young people to proclaim a kind of solidarity with an oppressed (but geographically very distant) people. Yet for whites to appropriate such music as performers – and especially to do so thousands of miles away – seemed to some to be at least inauthentic, if not as downright theft. British critics and emergent blues scholars like Paul Oliver viewed ‘white’ blues with abhorrence. White musicians, they argued, lacked the life experience of true bluesmen, and could never hope to match the qualities of ‘soul’ and raw emotional honesty that somehow automatically flowed from that.[38]

The problem here, of course, is that these arguments tend to essentialise racial difference, in ways that can prove problematic. They assign cultural and (in some instances) political value to the ‘blackness’ of particular forms of music, but they implicitly reproduce assumptions that black people are (or should be) more spontaneous, more natural – and ultimately more primitive – than whites. In the process, leading performers come to be seen as little more than ‘noble savages’.[39] The fetishizing of early rural blues entailed a romanticisation of poverty and suffering: it arguably reinforced images from which younger African-American audiences in particular were seeking to escape.

Aside from anything else, these views tend to neglect the diversity and ongoing development of the music itself. ‘Black’ and ‘white’ forms of music are seen to exist in hermetically sealed compartments. Yet blues was always ‘contaminated’ and never ‘pure’: like related forms such as jazz, it has always been an eclectic, hybrid genre. Early blues artists drew upon (and performed) material from a range of sources, including Hispanic and ‘Western’ popular and religious music. Despite the marketing practices of the music business (which assigned most African-American performers to the category of ‘race records’), and despite Jim Crow laws, blues was a syncretic, ‘creolized’ form, and the boundaries between different musical styles and genres were constantly blurring and shifting. The archival recordings of rural blues from the 1930s and 1940s so treasured by some British collectors were made at the same time as original rhythm and blues recordings of artists like Louis Jordan and Earl Bostic, which might be seen as a kind of proto-rock-and-roll. By the 1950s, a significant proportion of the songs that made the American R&B charts (formerly known as ‘race’ music) were by white artists.[40] Performers like Leadbelly (Huddie Ledbetter), who was very influential in the British scene, were understood as rural Southern ‘bluesmen’, but had evolved into sophisticated, professional urban entertainers, playing a diverse range of styles. And of course, as British audiences soon discovered, the music had developed over time, especially in the electric urban blues of Northern cities like Chicago. To regard blues in fundamentally retrospective, ‘folkloric’ terms was to freeze it in time and place, and to imply that any change was inevitably a corruption or dilution of a supposedly pure original.[41]

Aside from anything else, these views tend to neglect the diversity and ongoing development of the music itself. ‘Black’ and ‘white’ forms of music are seen to exist in hermetically sealed compartments. Yet blues was always ‘contaminated’ and never ‘pure’: like related forms such as jazz, it has always been an eclectic, hybrid genre. Early blues artists drew upon (and performed) material from a range of sources, including Hispanic and ‘Western’ popular and religious music. Despite the marketing practices of the music business (which assigned most African-American performers to the category of ‘race records’), and despite Jim Crow laws, blues was a syncretic, ‘creolized’ form, and the boundaries between different musical styles and genres were constantly blurring and shifting. The archival recordings of rural blues from the 1930s and 1940s so treasured by some British collectors were made at the same time as original rhythm and blues recordings of artists like Louis Jordan and Earl Bostic, which might be seen as a kind of proto-rock-and-roll. By the 1950s, a significant proportion of the songs that made the American R&B charts (formerly known as ‘race’ music) were by white artists.[40] Performers like Leadbelly (Huddie Ledbetter), who was very influential in the British scene, were understood as rural Southern ‘bluesmen’, but had evolved into sophisticated, professional urban entertainers, playing a diverse range of styles. And of course, as British audiences soon discovered, the music had developed over time, especially in the electric urban blues of Northern cities like Chicago. To regard blues in fundamentally retrospective, ‘folkloric’ terms was to freeze it in time and place, and to imply that any change was inevitably a corruption or dilution of a supposedly pure original.[41]

It seems likely that audiences took a more inclusive view of what counted as blues (and indeed as jazz or folk) than the critical police; and as more American blues music became available, and as the British rhythm and blues scene evolved and moved into the mainstream, the ‘authenticist’ argument became much harder to sustain. Equally, as with jazz, some performers were more ‘purist’ than others; and as we’ll see, this was one of the issues at stake in Alexis Korner’s split from his long-term musical partner Cyril Davies. I consider the musical implications of this in the following sections.

A changing industry

One of the many distinctions that began to blur in the popular musical cultures of the 1950s and 1960s was that between amateur and professional. On the one hand, the music industry itself was expanding and changing, especially with the rapidly growing market for recordings. The record business quickly came to be dominated by a small number of ‘majors’, and it was also serving an increasingly global (or at least transatlantic) market. Meanwhile, broadcasting was also expanding. A new commercial TV channel was launched in 1955, and Radio Luxembourg was also broadcasting pop music to a growing British audience; and while the BBC was wary and slow to adapt, it did so eventually. The potential for record sales was coming to drive live music, rather than vice-versa, as record companies themselves increasingly promoted live gigs, as well as the use of music on radio and television, and coverage in print media. And, as I’ve also noted here, young people were the key market in this respect. Dance bands and variety shows gradually fell out of fashion, partly displaced by television, but also by newly emerging musical styles with particular appeal to youth.[42]

On the other hand, from the later 1950s onwards, one can also see the rise of a new kind of ‘amateurism’ in popular music: genres such as revivalist and traditional jazz, rock-and-roll and skiffle all provided new opportunities for mass participation. The skiffle ‘boom’ was probably the clearest and earliest example of this. The music itself emerged from the revivalist jazz scene, especially from Chris Barber’s band: the renowned traditionalist Ken Colyer, along with Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies and the leading skiffle ‘star’ Lonnie Donegan were among those who performed skiffle in the intermissions between sets of the full band. While many early skiffle performers were no longer teenagers, and some were professional musicians, the genre was rapidly taken up by a vast number of amateur youth bands, many of them formed in schools. The music was played on acoustic instruments, some of which (like tea-chest basses and washboards) were home-made or repurposed: entry costs were low. (It’s worth noting that although the music was inspired by American performers – especially by folk musicians like Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly – it was a distinctively British hybrid with few US rivals at the time.)

While the vast majority of amateur skiffle bands quickly fell by the wayside, one could argue that these new genres did at least offer new routes into a professional career in music for some. In the process, they also entailed new forms of ‘do-it-yourself’ musical learning.[43] It was possible to teach yourself a few basic chords on the guitar, quickly form a band, and learn your craft by performing in front of a public audience, effectively as beginners: it seemed that formal academic training, or even a long-term process of apprenticeship with more experienced players, was no longer required. To some extent, skiffle was an instance of what Simon Frith calls ‘folk discourse’, in the sense that it sought to minimise the distance between the performer and the audience;[44] although its leading exponent, Lonnie Donegan, quickly progressed to mainstream showbiz stardom. Even so, its emergent ‘do-it-yourself’ ethos was still apparent in the rise of rhythm and blues, and has been an abiding influence in popular music ever since.

While the vast majority of amateur skiffle bands quickly fell by the wayside, one could argue that these new genres did at least offer new routes into a professional career in music for some. In the process, they also entailed new forms of ‘do-it-yourself’ musical learning.[43] It was possible to teach yourself a few basic chords on the guitar, quickly form a band, and learn your craft by performing in front of a public audience, effectively as beginners: it seemed that formal academic training, or even a long-term process of apprenticeship with more experienced players, was no longer required. To some extent, skiffle was an instance of what Simon Frith calls ‘folk discourse’, in the sense that it sought to minimise the distance between the performer and the audience;[44] although its leading exponent, Lonnie Donegan, quickly progressed to mainstream showbiz stardom. Even so, its emergent ‘do-it-yourself’ ethos was still apparent in the rise of rhythm and blues, and has been an abiding influence in popular music ever since.

How does Alexis Korner’s story fit in to this rapidly changing situation? As I’ve noted, Korner was essentially a self-taught musician. He never learned to read or write music particularly well, which caused him some difficulties, for example when he became the musical director of a children’s television show. His lack of self-confidence was reflected in the fact that in his early appearances (for example with Chris Barber) he was not especially keen to solo, or even to play loud; and this is also apparent in some of the recordings of this band. For much of the 1950s, he was essentially an amateur, or at most a ‘semi-pro’ musician; but throughout his life, he was earning much of his income from activities outside performing and recording. Venues like the Ealing Club, which he formed, also blurred the boundary between amateur and professional: eager fans could be in the audience one week and brought up on stage the next – and in some rare cases, on their way to a recording contract and global stardom by the end of the year. Yet as I’ve suggested, Korner was able to work across the various sectors of the music business: he was a musician, but he was also a critic, a DJ and broadcaster, a promoter, and a kind of teacher.

Musically, Korner also worked across a range of genres and scenes. While he quickly abandoned skiffle, and became primarily identified with blues and R&B, he also played with traditional and modern jazz musicians, and with folk and rock (and indeed pop) artists. He performed regularly in folk clubs like London’s Troubadour, and at folk festivals. Among its shifting personnel, his band Blues Incorporated included several noted modern jazz musicians, and played tunes by Charles Mingus and Duke Ellington. While Cyril Davies eventually left the band because he felt it was becoming too jazz-oriented, with the inclusion of musicians like Jack Bruce (then playing double bass), Ginger Baker and Graham Bond, the latter eventually left because they felt it was not jazzy and adventurous enough. Unlike Davies, Korner was by no means a purist, although he drew the line at rock-and-roll: he was not fond of blues-related rock performers like Chuck Berry, for example. Even so, such generic boundaries may well have been much more fluid and permeable at this time than they are today.[45]

Towards British blues

What are the implications of all this for Korner’s music itself? His recordings at this point were relatively few and far between, and in some instances the details of personnel and recording dates are not entirely clear.[46] In his early career, Korner seems to have regarded recordings as a kind of ‘calling card’ that would help to interest promoters and obtain live gigs, rather than significant musical statements in their own right. As such, the available recordings may be little more than a shadow of the experience of hearing a live performance; but they are all we have.

Questions can also be raised here about the quality of the production and recording technology. Companies like Decca – the British ‘major’ where most of these recordings were made – were largely oriented towards classical music, and to some extent jazz. Korner and his associates frequently complained about such companies’ lack of interest in blues (and later rhythm and blues). Unlike their American counterparts, British producers and recording engineers were slow to adjust to the very different demands of such music. These limitations were thrown into stark relief when bands like the Rolling Stones later toured in the United States and experienced the studios of labels like Chess and Stax at first hand.

Questions can also be raised here about the quality of the production and recording technology. Companies like Decca – the British ‘major’ where most of these recordings were made – were largely oriented towards classical music, and to some extent jazz. Korner and his associates frequently complained about such companies’ lack of interest in blues (and later rhythm and blues). Unlike their American counterparts, British producers and recording engineers were slow to adjust to the very different demands of such music. These limitations were thrown into stark relief when bands like the Rolling Stones later toured in the United States and experienced the studios of labels like Chess and Stax at first hand.

Korner’s first recorded appearances were on a cluster of tracks billed as ‘Ken Colyer’s Skiffle Group’ (the spin-off from the larger Chris Barber band), made between 1954 and 1956. These are small groups, with a washboard, a banjo and a string bass. Korner’s contributions on acoustic guitar and mandolin are relatively low in the mix, and the tempo on several tunes tends to speed up. Colyer sings in a fairly accurate American accent, although this is sometimes exaggerated; and while he uses a convincing vibrato, his articulation is still comparatively clean and ‘British’.

In 1957 and 1958 Korner recorded two sessions under his own name (as ‘Alexis Korner’s Skiffle Group’ and then ‘Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated’) under the title Blues From the Roundhouse, Volumes 1 and 2 – which despite the title, were in fact recorded at the Decca studio in West Hampstead. The style here has elements of skiffle, although it is generally closer to country blues. The repertoire includes some distinctly ‘folkish’ tunes (such as ‘Skip to my Lou’, with Korner on mandolin), as well as Southern blues (‘Boll Weevil’). The instrumentation includes a washboard and a string bass, and Korner’s acoustic guitar is mostly strummed rather than used for solos. Cyril Davies’ harmonica playing is powerful and convincing, although (like Colyer’s) his vocals are rather functional, with very little melisma or improvisation. The beat tends to be placed very squarely and inflexibly. Once again, as in the appropriately named ‘Ella Speed’, the tempo tends to accelerate; and, as in ‘Streamline Train’, the rhythm is sometimes awkwardly placed. Korner’s occasional vocals (on tunes like ‘Streamline Train’ and ‘Kid Man’) are partly declaimed rather than sung, and wander off-pitch at times. However, on some other tunes from the same sessions, such as ‘Death Letter’ and ‘Easy Rider’, the lead vocals by Beryl Bryden (or possibly Ottilie Patterson) are significantly more powerful, and much better recorded, with appropriate (and occasionally more-than-appropriate) use of reverb.

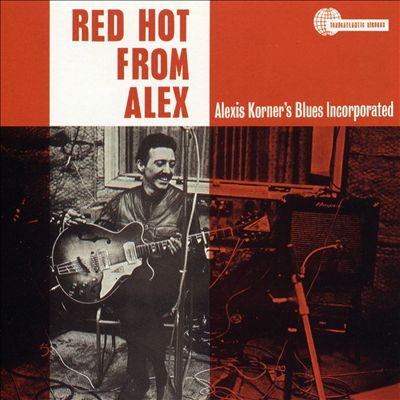

Various one-off recordings backing visiting US singers (including Memphis Slim, Champion Jack Dupree and Roosevelt Sykes) followed in 1960 and 1961, but it was not until 1962 that Korner recorded again under his own name as ‘Blues Incorporated’, in a full-length album entitled R&B From the Marquee – again, despite the title, recorded at Decca studios.[47] A further album, simply entitled Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, was recorded in 1963 but not issued until 1965, by which point the band’s personnel had changed significantly. In the first of these, Korner uses Dick Heckstall-Smith on saxophone – a ‘jazz’ instrument apparently abhorred by Davies – and on the second, with Davies now departed, he adds a further saxophonist in Art Themen, and a new drummer and bass player, Phil Seamen and Spike Heatley, all of them well-known modern jazz musicians. The use of these (and other) jazz players occasionally takes the music into a different idiom, with double-time elements and some harmonic departures in the solos, as compared with Davies’s much more rhythmically straightforward, diatonic harmonica. By contrast, Korner sticks with his semi-acoustic style, in a kind of uneasy compromise with country blues, and his solos are somewhat routine.

Again, the repertoire is fairly diverse. There are some uneventful, chugging instrumentals, and some jovial novelty songs with suggestive, almost vaudevillian lyrics (‘Keep Your Hands Off’, ‘I Put a Tiger in Your Tank’). In the earlier session, Davies contributes vocals on a couple of Muddy Waters covers (‘I Got my Brand on You’, and ‘Got my Mojo Working’), which again serve only to demonstrate the distance between him and Waters: despite his best efforts, the vocals lack depth and abrasiveness, and the articulation is unusually clean in comparison with the originals. By contrast, the appearance of Long John Baldry on vocals comes as something of a revelation. On tunes like ‘Rain is Such a Lonesome Sound’ and ‘How Long, How Long Blues’, he takes ownership of the material, displaying considerable command and conviction: swooping bent notes, shouts, improvised embellishments, rhythmic delays, and even tearful vibrato all provide a level of drama that is lacking elsewhere. Again, this is accentuated by the production: while much of the sound is rather thin (especially Heckstall-Smith’s tenor sax), it is as though the engineers have suddenly decided to turn on the reverb. Baldry was just 21 years old at the time, one of the earliest members of a new generation of British R&B performers.

Again, the repertoire is fairly diverse. There are some uneventful, chugging instrumentals, and some jovial novelty songs with suggestive, almost vaudevillian lyrics (‘Keep Your Hands Off’, ‘I Put a Tiger in Your Tank’). In the earlier session, Davies contributes vocals on a couple of Muddy Waters covers (‘I Got my Brand on You’, and ‘Got my Mojo Working’), which again serve only to demonstrate the distance between him and Waters: despite his best efforts, the vocals lack depth and abrasiveness, and the articulation is unusually clean in comparison with the originals. By contrast, the appearance of Long John Baldry on vocals comes as something of a revelation. On tunes like ‘Rain is Such a Lonesome Sound’ and ‘How Long, How Long Blues’, he takes ownership of the material, displaying considerable command and conviction: swooping bent notes, shouts, improvised embellishments, rhythmic delays, and even tearful vibrato all provide a level of drama that is lacking elsewhere. Again, this is accentuated by the production: while much of the sound is rather thin (especially Heckstall-Smith’s tenor sax), it is as though the engineers have suddenly decided to turn on the reverb. Baldry was just 21 years old at the time, one of the earliest members of a new generation of British R&B performers.

Korner’s recordings over this period are not necessarily the most reliable guide, but they do suggest that – as the rhythm and blues boom gathered pace – younger musicians were not merely trying to reproduce the American originals, but to create their own distinctive style, which was more energetic, and arguably closer to pop and rock-and-roll. Faced with a rising tide of relatively inexperienced bands, the critics were working overtime to condemn their lack of authenticity: British performers, they argued, were simply ‘putting on the style’, singing in false American accents, in a kind of parody of the real thing. As the bands that emerged from Blues Incorporated began to appear in the charts, the charge of ‘selling out’ inevitably followed. Yet as Roberta Schwartz suggests, this might have been much more of a preoccupation for the critics than for the performers – who were not claiming to be authentic in the first place – or indeed their audiences – for whom it might well not have mattered.[48]

So could white boys ever hope to sing or play the blues? Ultimately, it’s hard to know how we might answer this question. Self-evidently, this was not ‘black’ music, at least in the sense that it was performed almost exclusively by white artists. We might attempt to identify musical signifiers of ‘blackness’ – for example in the vocal expression, or the ‘grain’ of the voice; the instrumental style, for example the use of ‘bent’ notes or melisma (rather than simply flattened fifths or thirds); the rhythm, and especially the relationship between the melody and the beat; and the structure, for example the more or less rigorous adherence to a harmonic form like the 12-bar sequence. Yet these elements are all fluid in themselves, and combine in different ways; and they do so in the context of an always-evolving, hybrid form. The question of what counts as ‘black’ music, or as ‘authentic’ blues, quickly leads to a kind of absurdity: are some performers more ‘black’ than others, and on what basis would we make such a judgement?

Conclusion

In his influential book Subculture, published in 1979, Dick Hebdige suggests that the story of youth culture can be seen as a ‘phantom history of race relations’ in post-War Britain.[49] The rhythm and blues boom of the early 1960s was just one key moment in this longer post-imperial history; but as I’ve tried to show, there were some significant complexities and ironies in this respect, which partly derive from the transatlantic nature of the phenomenon. White British fans were discovering blues at a time when it was in decline among black American audiences. Arguably, black American audiences now considered blues (and especially country blues) to be old-fashioned ‘hick’ music: they wanted something more sophisticated and contemporary, not something that would remind them of slavery.[50] Bands like the Rolling Stones made their breakthrough in the US by selling a version of ‘black’ music to young white American audiences, many of whom had probably never heard such music before. Of course, it made a difference that it was good looking white boys, rather than old black men; and while they paid respect to the original artists (for example in interviews), they didn’t pay them any of the money that they earned from doing so. Meanwhile, contemporary black American blues musicians like Robert Cray claim they were learning as much from Eric Clapton as they were from recordings of black artists like Jimi Hendrix.[51]

The British rhythm and blues boom could be interpreted primarily as a matter of youthful rebellion. Elements of it were certainly consistent with that. Yet as I hope this essay has shown, there was more at stake in all this, especially to do with ‘race’. Once again, what we can see here is a gradual loosening of established categories and a blurring and consequent re-drawing of cultural boundaries – a process which was uneven and ambivalent as much as it was liberating. Alexis Korner’s significance here lies not so much in his own music as in his nurturing of a new generation that was rapidly heading in new directions.

Notes

[1] The precise details of all these events have been rehearsed and contested countless times. In researching this essay, I have made use of some published histories (as cited), but also a range of other media sources. These include fan sites, especially for Korner and Davies: https://alexis-korner.net/ and http://www.cyrildavies.com/index.html; and BBC television documentaries, including The British R and B Boom of the Sixties (1995) in the series Rock Family Trees (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DAgk6AioME), and How Britain Got the Blues (2013) in the BBC4 series Blues Britannia (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kS_l3YLLUBE).

[2] These estimates come from Schwartz (2007), p. 134.

[3] For a good critique, see Stilwell (2004).

[4] According to the Tom Robinson documentary, note 5.

[5] Information here is drawn primarily from the biography by Shapiro (1996). I have also made use of a couple of BBC radio documentaries, Alexis Korner: The Story of the British Blues Guitarist (2008), narrated by Chris Jagger (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pw4ekD_HWkY) and a BBC Radio 2 programme, narrated by Tom Robinson (1999), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZuE_LJbTta8).

[6] Frame (2007), p. 97.

[7] For an account from the perspective of the ‘high sixties’, see Birchall (1968).

[8] Frame (op. cit.).

[9] See note 1 above. A very similar account occurs in the documentary on the Ealing Club, Suburban Steps to Rockland: The Story of the Ealing Club (dir. Giorgio Guernier, 2017), and in Shapiro’s biography of Korner.

[10] Nead (2017). The term ‘structure of feeling’ is drawn from Raymond Williams (1958).

[11] This interpretation is offered by (among others) Schwartz (op. cit.), p. 74ff.

[12] Schwartz (ibid.) provides a useful pre-history here; while Frith et al. (2013) document official efforts to police live music at this time.

[13] Shapiro (op. cit.), Chapter 2.

[14] See Lorre (2020).

[15] One of the very few exceptions here was the writer and photographer Val Wilmer, who (like Korner) hosted many visiting Americans (see her 1989 memoir).

[16] Again, see Lorre (op. cit.) and Schwartz (op. cit).

[17] Quotes taken from (respectively) the Chris Jagger radio documentary, and the Ealing Club documentary (notes 5 and 9 above).

[18] Schwartz, op. cit.

[19] There has been some rather tiresome academic debate on all this: see Hesmondhalgh (2009) for a balanced account.

[20] For debate on these issues, especially relating to this period, see Lyons (2013), Chapters 1 and 2.

[21] Harker (1980), pp. 100-101.

[22] See Frith et al. (op. cit.).

[23] There are numerous accounts of these clubs written by former participants: see, for example, Brookfield (2022). The scene in Richmond and Twickenham is well described by Humphreys (2022), and I have written about this elsewhere: https://davidbuckingham.net/2022/04/05/a-suburban-scene-youth-and-music-in-sixties-london/.

[24] See Hennessy (2016).

[25] On the relation between ‘folk’ and ‘pop’ discourses in music, see Frith (1996); and on Leavis and his followers, Hilliard (2012).

[26] Hennessy (op. cit.).

[27] See also Schwartz (op. cit.).

[28] For a very accessible, broad-ranging account, see Barker and Taylor (2007).

[29] The idea of ‘subcultural capital’ is developed by Thornton (1995).

[30] For historical studies, see McKay (2005) and Heining (2012).

[31] See Frith (op. cit.).

[32] See, for example, Hamilton (2007); and on the transatlantic aspect, O’Connell (2013).

[33] See Wald (2004); and Barker and Taylor (op. cit.).

[34] For a thoughtful account, see Cole (2018).

[35] Waters was not the only visiting American who felt obliged to recreate what he saw as a past style; John Lee Hooker had a similar experience. Waters was not the first to play electric blues in the UK either: the gospel singer Sister Rosetta Tharp had done so the previous year.

[36] Again, it’s worth noting that this question has not disappeared: there were similar debates about the authenticity of ‘blue-eyed soul’ in the 1970s, or of white rappers in the 1990s and 2000s.

[37] Schwartz (op. cit.) provides a comprehensive account of these responses.

[38] See O’Connell (op. cit.).

[39] See Barker and Taylor (op. cit.).

[40] According to Perchard (2014).

[41] For further debate on these issues, see Gilroy (1991) and Stilwell (op. cit.).

[42] For a full account, see Frith et al. (op. cit.), especially Chapter 6. On the youth market, see also here.

[43] See Frith et al. (ibid.), especially Chapter 2; and on musical learning, Green (2002).

[44] Frith (op. cit.).

[45] As suggested by Frith et al. (op. cit.).

[46] I have relied on the discography in Shapiro (op. cit.), but some of the information does not correspond to the recordings, not least because many of the tracks have been repackaged and reissued in several forms. Shapiro also provides useful information about the recording sessions, and the critical response to these albums.

[47] There is also a short film of the band’s appearance on BBC Jazz Club (on radio), recorded the following month: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DKeg4IdnLL4.

[48] Schwartz (op. cit.).

[49] Hebdige (1979), p. 45.

[50] This suggestion is made in the Blues Britannia documentary, How Britain Got the Blues.

[51] According to Schwartz (op. cit.).

References

Barker, Hugh and Taylor, Yuval (2007) Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music London: Faber

Birchall, Ian (1968) ‘The decline and fall of British rhythm and blues’, in Jonathan Eisen (ed.) The Age of Rock: Sounds of the American Cultural Revolution New York: Random House

Brookfield, Ralph (ed.) (2022) Rock’s Diamond Year Twickenham: Supernova

Cole, Ross (2018) ‘Mastery and masquerade in the transatlantic blues revival’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 143(1): 173–210

Frame, Pete (2007) The Restless Generation: How Rock Music Changed the Face of 1950s Britain London: Rogan House

Frith, Simon (1996) Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Frith, Simon, Brennan, Matt, Cloonan, Martin and Webster, Emma (2013) The History of Live Music in Britain, Volume 1: 1950-1967 Aldershot: Ashgate

Gilroy, Paul (1991) ‘Sounds authentic: Black music, ethnicity, and the challenge of a changing same’, Black Music Research Journal, 11(2): 111-136

Green, Lucy (2002) How Popular Musicians Learn Aldershot: Ashgate

Hamilton, Marybeth (2007) In Search of the Blues: Black Voices, White Visions London: Jonathan Cape

Harker, Dave (1980) One for the Money: Politics and Popular Song London: Hutchinson

Heining, Duncan (2012) Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers: British Jazz, 1960-1975 Sheffield: Equinox

Hennessy, Tom (2016) Beyond Authenticism: New Approaches to Postwar Music Culture unpublished PhD thesis, London: Birkbeck College, University of London

Hesmondhalgh, Dave (2009) ‘Recent concepts in youth cultural studies: critical

reflections from the sociology of music’, pp. 37-50 in Paul Hodkinson and Wolfgang Diecke (eds.) Youth Cultures: Scenes, Subcultures and Tribes London: Routledge

Hilliard, Christopher (2012) English as a Vocation: The ‘Scrutiny’ Movement Oxford: Oxford University Press

Humphreys, Andrew (2022) Raving Upon Thames: An Untold Story of Sixties London London: Paradise Road

Lorre, Sean (2020) ‘”Mama, he treats your daughter mean”: Reassessing the narrative of British R&B with Ottilie Patterson’, Popular Music 39(3-4): 482-503

Lyons, John F. (2013) America in the British Imagination: 1945 to the Present Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

McKay, George (2005) Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain Durham NC: Duke University Press

Nead, Lynda (2017) Tiger in the Smoke: Art and Culture in Post-War Britain London: Yale University Press

O’Connell, Christian (2013) ‘The color of the blues: considering revisionist blues scholarship’, Southern Cultures 19(1): 61-81

Perchard, Tom (2014) ‘Introduction’, pp. xi-xxix in Tom Perchard (ed.) From Soul to Hip-Hop Basingstoke: Ashgate

Schwartz, Roberta Freund (2007) How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom Aldershot: Ashgate

Shapiro, Harry (1996) Alexis Korner: The Biography London: Bloomsbury

Stilwell, Robynn (2004) ‘Music of the youth revolution: rock through the 1960s’, pp. 418-452 in Cook, Nicholas and Pople, Anthony (eds.) Cambridge History of Twentieth Century Music Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Thornton, Sarah (1995) Club Cultures Cambridge: Polity

Wald, Elijah (2004) Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues New York: Amistad

Williams, Raymond (1958) Culture and Society 1780-1950 London: Chatto and Windus

Wilmer, Valerie (1989) Mama Told Me There’d Be Days Like This London; Women’s Press

David Buckingham, May 2023

Please cite with web address: http://www.davidbuckingham.net